In Wisconsin, high rates of probation and parole are contributing to its growing, racially disparate prison population, according to a new report from Columbia University’s Justice Lab.

Wisconsin has the highest rate of parole supervision among its neighboring states, and the lengths of parole are nearly twice the national average.

“Probation and parole, collectively called corrections or community supervision, has been a bit of an invisible arm of correctional control in the United States,” said Kendra Bradner, senior staff associate at the Justice Lab.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Probation typically refers to supervision given in lieu of a prison sentence, whereas parole, more often known in Wisconsin as “extended supervision,” refers to the supervision following a period of incarceration. In the Justice Lab report, Bradner and her colleagues argue that mass supervision drives mass incarceration, especially in Wisconsin.

In 2016, there were almost as many people on probation or parole as people living in the city of Oshkosh.

“What that looks like on the day to day in our communities is 65,000 people invisibly shackled,” said Robert Agnew Jr., an organizer with JustLeadershipUSA, which commissioned the study. Agnew was formerly incarcerated and supervised, meaning he has first-hand knowledge of the effects of forces detailed in the report.

In Wisconsin, the terms of probation and parole are often strict, and the state’s truth-in-sentencing statute and parole-expansion laws — passed in the 1990s — makes it even more so. Offenders can no longer end their incarceration early because of good behavior, and, upon release, they must serve an additional period of “extended supervision” amounting to at least one-quarter of their original sentence. These laws create myriad opportunities for people to transgress, accidentally or otherwise, which can land them back in jail.

The study found that, in 2017, almost half of Wisconsin’s adult prison population was comprised of people on community supervision, an umbrella term for probation and parole. It also found that over one-fifth of the adult prison population was incarcerated for violating the terms of their probation or parole — not for conviction of another crime.

“Re-incarceration for technical rule violations is a culture, it is a power tool that keeps Wisconsin’s prison population at its max and beyond max,” said Agnew. Wisconsin’s prison population has more than tripled since 1990, but prison growth has not resulted from an increase in crime, according to the report.

“It’s not just Milwaukee or Madison, but it is a Wisconsin issue,” said Agnew. “Because we are all, whether we know it or not, financially invested in corrections as it stands.”

The Justice Lab researchers found that people re-incarcerated without a new offense spend an average of 1.5 years in prison and cost taxpayers $147.5 million.

Wisconsin ranks fifth worst for racial disparities in prison incarceration, and the report dug into how those disparities break down in parole and probation. The Justice Lab researchers found that one in eight black men and one in 11 Native American men are under some form of community supervision in the state. Black women, meanwhile, are supervised at three times the rate of white women, and Native American women are supervised at six times the rate of white women.

“When we look at incarceration in Wisconsin, what you find is that these high incarceration numbers have a correlation with the high poverty that we find in black and native communities, communities of color,” said Agnew.

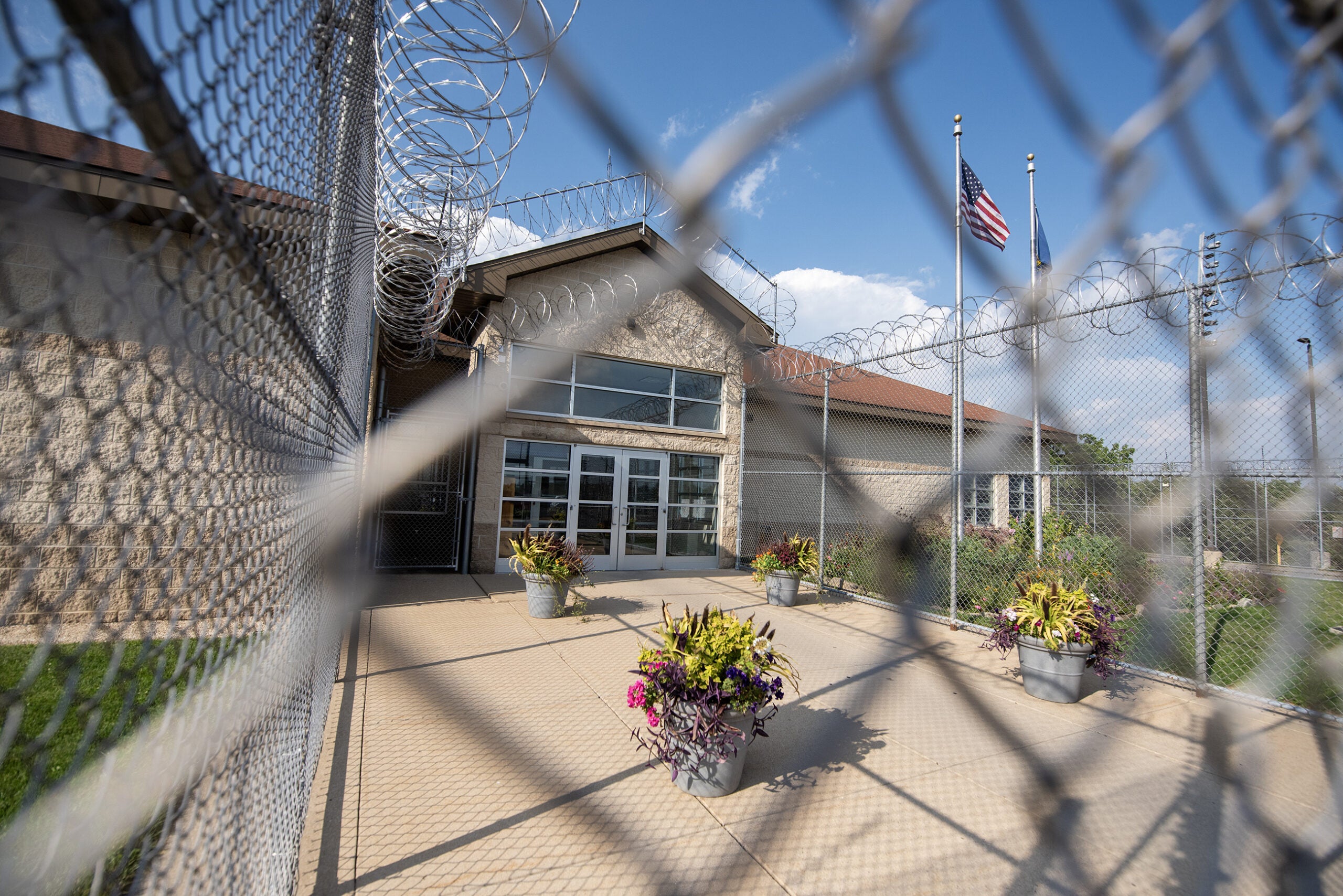

According to the researchers, one particular institution, the Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility, starkly reflects the consequences of Wisconsin’s current community supervision regime, particularly on communities of color. MSDF, which opened in 2001, is the first state facility in the nation built primarily for incarcerating those under community supervision. Currently, 86 percent of people held in MSDF for revocations didn’t get convicted of another crime. At the end of 2017, 76 percent of all people incarcerated for revocations were black, and 88 percent of those didn’t have another conviction. Overall, 65 percent of people in MSDF identify as black.

Grassroots activists and organizers have campaigned to shut down MSDF for several years, including Agnew of JustLeadershipUSA.

During his campaign, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers said he supported closing MSFD “as soon as possible.” He also campaigned on larger policy changes similar to the report’s recommendations, including reducing parole revocations and overhauling truth-in-sentencing rules. His staff did not return a request for comment.

The Department of Corrections provided a statement via email, writing that its staff is currently reviewing the report.

“Under Governor Evers’ leadership, DOC is prioritizing the reduction of Wisconsin’s prison population and the reduction of crimeless revocation. Secretary-designee Kevin A. Carr is actively engaged in finding ways to empower offenders toward successful re-integration into their communities following release while maintaining the Department’s top priority of public safety,” the statement read.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.