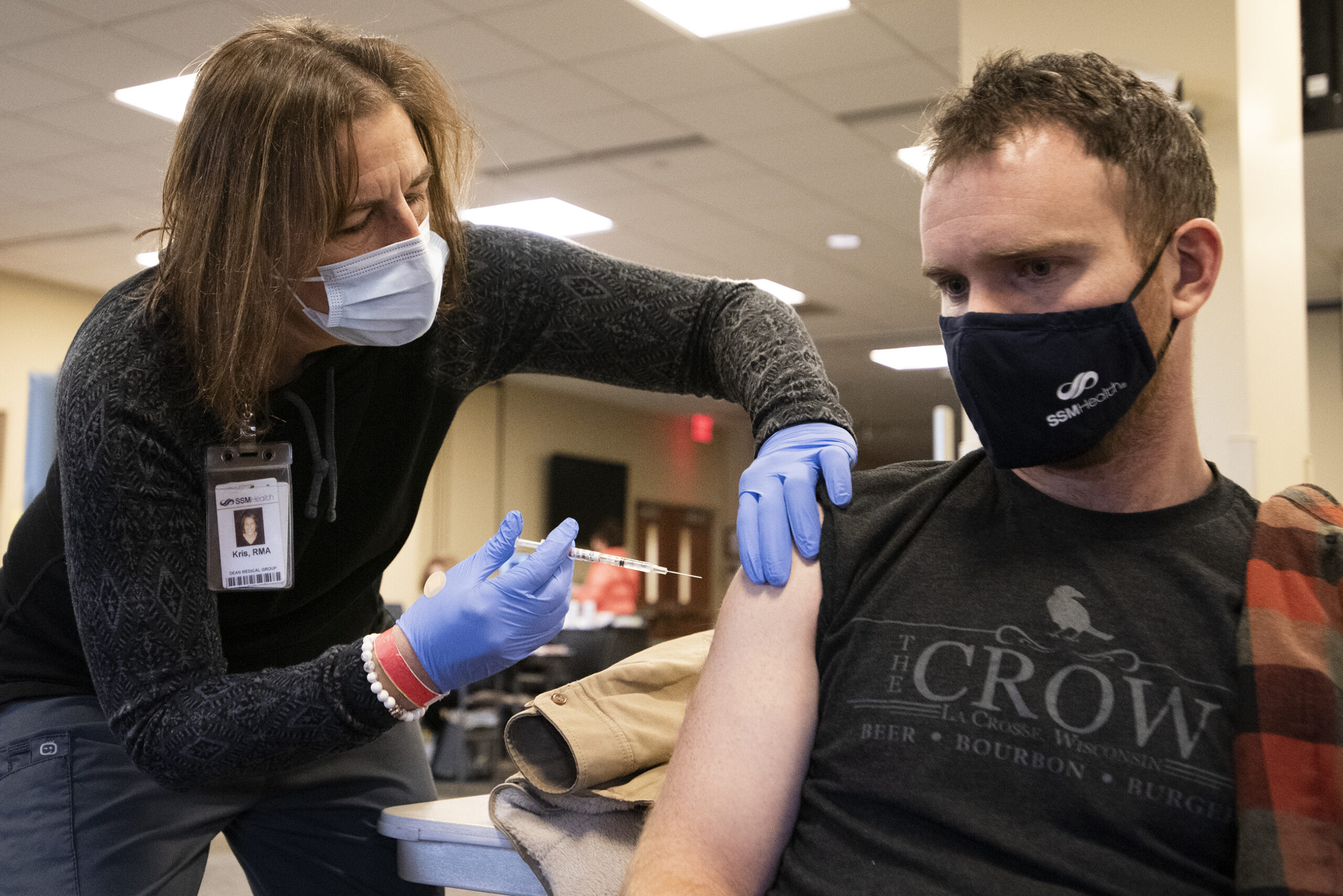

People in rural areas are less likely than any other group to say they will definitely get vaccinated against COVID-19, according to a new survey, creating new challenges in protecting people from the illness.

New polling data released this month by the Kaiser Family Foundation found hesitancy or skepticism about the vaccine in several demographic groups, including Republicans, Black adults and people between the ages of 30 and 49. But adjusted for those and other demographic factors such as income, people living in rural communities were still the least likely to say that they would definitely get the vaccine (31 percent of rural residents compared to 41 percent of all respondents) and the most likely to say they definitely would not (20 percent of rural residents compared to 15 percent of all respondents).

“Even when controlling for party identification and income and education, there’s something unique about living in a rural community that makes you more vaccine-hesitant than those living in urban and suburban communities,” said Ashley Kirzinger, Kaiser’s associate director for Public Opinion and Survey Research.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Those attitudes point to challenges for health officials in persuading enough rural residents to get the vaccine to achieve herd immunity from the disease.

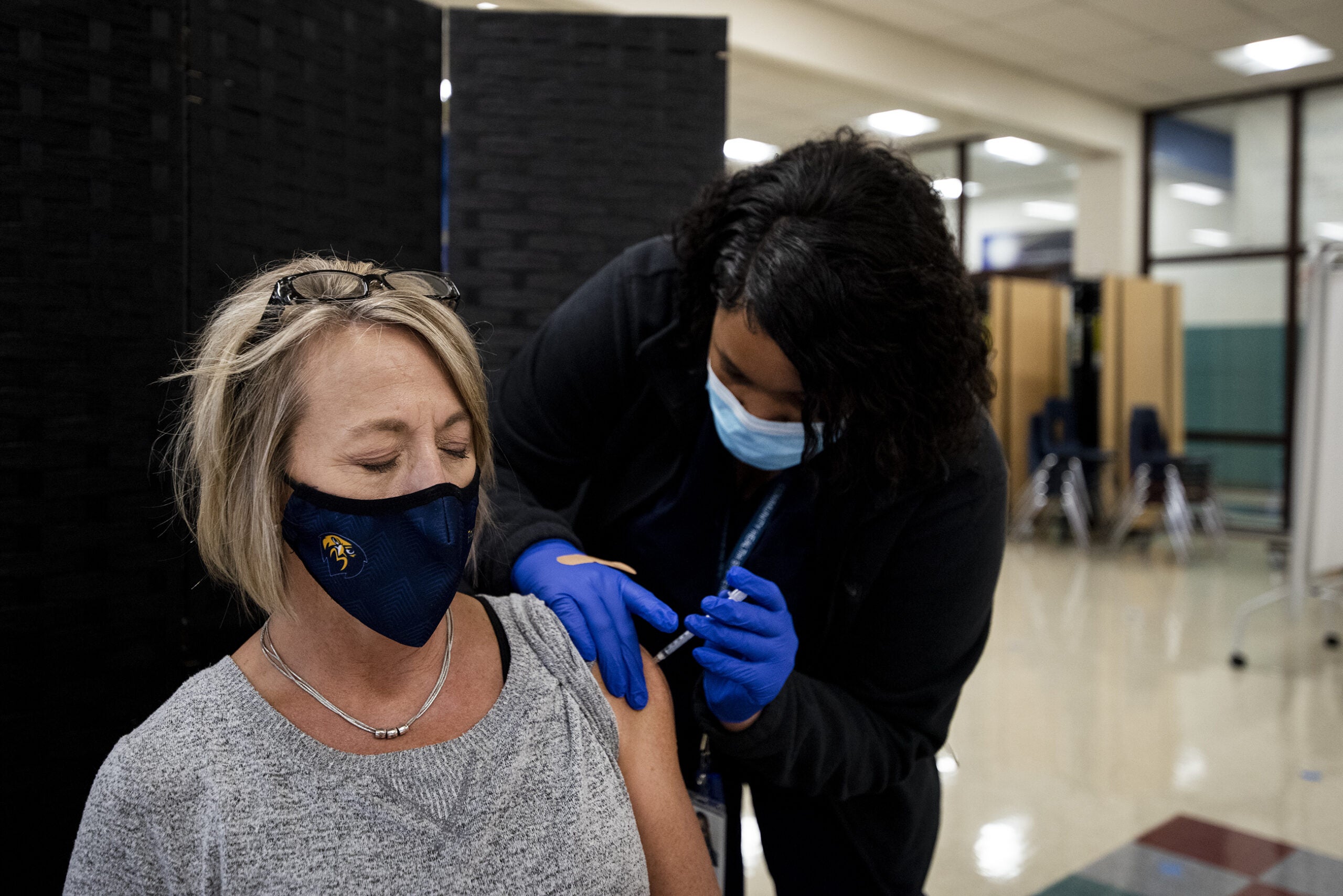

“Not everyone is an early adopter,” said Sara Wartman, Bayfield County health officer. “I’m planning a long-term strategy of (mass vaccination) clinics into 2022.”

So far, the rollout of mass vaccinations against the coronavirus has been slow and plagued with logistical challenges in Wisconsin and nationwide. Health officials say in order to stop the spread of the disease, a large majority of people will need to receive the vaccine — perhaps as many as 90 percent of people, according to federal health official Dr. Anthony Fauci. That means that as supplies and distribution efforts ramp up, public information campaigns will need to substantially increase, too.

Dr. Amy Slagle, medical director of the Menominee Tribal Clinic, said some clinic staff declined the vaccine.

“There are a substantial number of people who want to ‘wait and see’ what happens to others who get the vaccine — which clearly becomes an issue if 100 people are eligible for the vaccine and 50 percent of them decide to wait and see, then we’ll never get to herd immunity,” Slagle said.

In the first wave of the pandemic in early 2020, urban areas were hit much harder than rural places. But the virus spread to rural regions across the nation in the summer and fall. By October, rural parts of Wisconsin were among the hardest-hit places in the nation.

In Kaiser’s national poll, rural residents were just as likely as others to know someone who had contracted or died from COVID-19. But they were much less likely to be worried for themselves or members of their family. Thirty-nine percent said they were unworried, compared to 23 percent of urban residents and 30 percent of suburban residents.

“(The pandemic) hit rural areas just as hard as urban areas,” Kirzinger said. “But for some reason, there is this dominant narrative in people’s minds that it’s not going to hit them and their families — even if they know someone who’s died, which I thought was really striking.”

John Eich, director of the Wisconsin Office of Rural Health, said his office is working on reaching out to local city leaders and faith leaders to help promote vaccinations in rural communities.

“Can those folks help us encourage the population to do this?” Eich said.

Eich added that communication to people in rural areas about where and when they have the option to be vaccinated “needs to be robust in rural areas.”

Public opinion data show that different demographic groups have different reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Kirzinger said Republicans and rural residents were more likely to believe the risks of the disease were exaggerated. Black Americans were more likely to be broadly skeptical of medical advice. In all cases, though, the presence of trusted messengers who can recommend vaccination could begin to change people’s attitudes.

“In these small towns and rural areas in the U.S., people tend to know their doctor, and they place a lot of trust in their doctor,” Kirzinger said. Messages conveyed directly from rural physicians and other health providers will be “essential,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.