For more than 30 years, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Crocker Stephenson has relied on the power of observation to paint pictures of city life.

In 1996, Stephenson and Journal Sentinel photographer Gary Porter rented an apartment in a neighborhood on the city’s northwest side for a month. The purpose was to find out why four murders happened in one week in this neighborhood, an area not known for such violence. What Stephenson found was a young girl contemplating the violence:

A 12-year-old girl sits on a flight of green-carpeted steps just inside the doorway of a worn-out building. She rests her chin on her knees, watching an early morning rain pour down on the street outside.

She has black beads woven into her braided black hair. Her eyes are dark and sullen.

The rain sweetens the air, but the lightless hallway in which the child sits is stuffy and sour. Beads of sweat collect above her lips. Her skin glows in the shadows.

“Ain’t nothing to do but sit in the hallway till it stop,” she says. “Nothing to do till it stop.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Stephenson has covered crime, public health and an array of feature stories for the newspaper. He was sent to New York City in the aftermath of 9/11 and to Kosovo to cover the war in the late 1990s. His hallmark is writing with rich description and revealing detail.

“The most profound moments I’ve had as a journalist have been visual moments,” Stephenson said.

But now, at 63, Stephenson is losing his sight. Doctors cannot define the condition, but it’s similar to macular degeneration. It’s causing his world to look like a series of vague shapes and patches of light and dark. Doctors say his vision will continue to deteriorate.

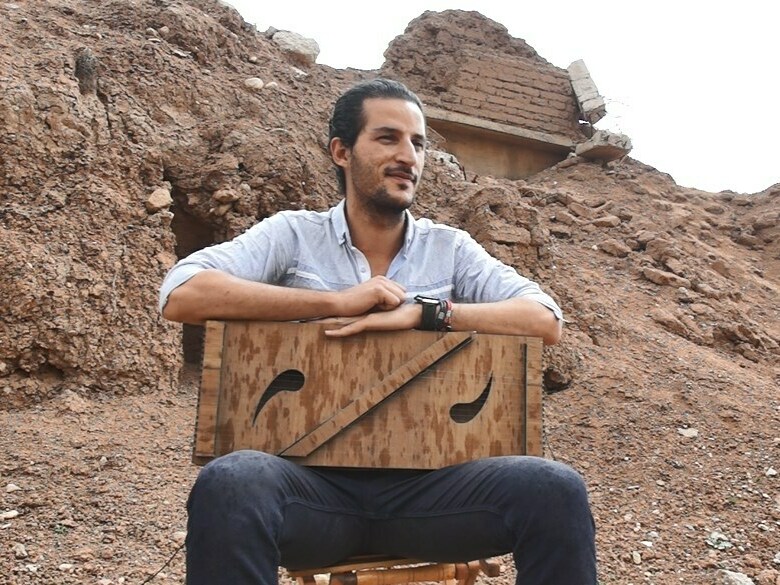

Crocker Stephenson uses a magnifying glass, an oversized monitor and special lights to help him read and write at his desk in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel newsroom. Jane Hampden/WPR

Stephenson can no longer see the beads in a little girl’s hair, or describe a worn-out Milwaukee apartment building. He can’t drive anymore, so he uses the bus to get around town. On the familiar walk from his home to the bus stop, he can barely recognize the outlines of houses or patches of glistening ice on the sidewalk.

“I can see the cars well enough to wait before I cross the street,” Stephenson says. “I’m not always able to see the stop signs or the electric signs so I have to use my ears.”

He’s also relying on his ears to tell stories.

“I used to have very, very few quotes in my stories, and now I use a lot of quotes, in part because I tape all my interviews,” Stephenson says. “And maybe I haven’t been listening to people well enough. I haven’t realized how revealing people can be with their own word choices or the word that a person comes up with after a long pause. My interviews have become much more intimate.”

Instead of taking notes on details he observes in the field, Stephenson sometimes asks interviewees to describe what they look like, or what they’re wearing.

Stephenson has won many awards for his work, but the most meaningful to him are the Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism, which he won three times, and the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering and Institute of Medicine Keck Communication Award for Empty Cradles, his 2011 series on infant mortality.

His fading sight has inspired a new column called Better Angels, stories about the graciousness and goodwill he’s discovered in Milwaukee since he started losing his vision about a year ago.

He’s written about a hospice physician confronting his own death, a team of women offering help to the homeless in the city’s darkest corners, and wildlife experts rehabilitating an injured snowy owl found in a Milwaukee parking lot. The column, which debuted last year at Thanksgiving, is a hit. Stephenson has never received so much feedback from readers.

Journal Sentinel Deputy Managing Editor Tom Koetting says even younger readers, coveted by news organizations, are sharing the stories and finding the column inspiring.

“Journalistically, it doesn’t compromise anything,” Koetting says. “We’re not just going for clicks on a computer. The grounding mission of good journalism is to report on what it’s like to live in this place at this time, and these stories are right down that alley.”

Stephenson has more story ideas from readers than time to pursue them. In the past, he said, he would have been cynical about a column that focuses on uplifting stories. Now he’s reconsidering.

“I think people want to have a reason to hope, to believe that the world children are growing up in isn’t, at its core, nasty, dangerous and brutal,” Stephenson said. “I want to evoke that kindness, that decency, that compassion.”

Stephenson has three children, twins in college and one who’s a teacher in New York City.

And while everyday people inspire Stephenson, to him, his wife Jeanne Dawson and her breast cancer diagnosis have had a profound influence on his approach to his vision loss.

“Her equanimity and bravery during this long period was astounding. Her willingness to embrace life for what it was, even when things were terrible and frightening, just altered things for me. She remained grateful for everything,” he said. “She never lost her delight in everyday-ness. All those things have come into play now, and the fact that she’s with me now is a gift.”

Stephenson’s vision may never go away entirely, but it will get worse and he doesn’t know what that will be like. So he’s not dwelling on it.

“I’m improvising as I go, and that’s the main way to approach this,” he said.

He often listens to books on tape, and at a museum recently, he learned there’s a phone app that you can install that allows you to point your phone at a sign and it reads the words aloud.

But no matter what happens, Stephenson will keep writing: “I can’t not write. If I can’t get to work, I’ll write from home.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.