An Oscar-nominated short documentary film features footage of a large German-American pro-Nazi group gathering in New York in 1939. And that group that has ties to Wisconsin. We hear from a historian and a director of the film to help us put this footage in context. We also talk with a cookbook author about her favorite Palestinian flavors and recipes. And we learn about an alleged domestic terrorism plot planned by a Coast Guard lieutenant.

Featured in this Show

-

New Cookbook Explores Palestinian Cuisine And Experience

A new cookbook is the work of an activist and chef, exploring not only the culinary traditions of Palestine, but also the experiences outside of the kitchen for Palestinians, including the Israeli Occupation. We talk with the author about the flavors of the food and the people behind it.

-

U.S. Coast Guard Lieutenant Accused Of Planning Act Of Domestic Terrorism

A lieutenant in the United States Coast Guard has been accused by federal prosecutors of planning a domestic terror attack after stockpiles of gun and ammunition were found at his home. Federal prosecutors also allege that the man had a list of potential targets, including high-profile journalists and Democratic lawmakers. We learn more about the story with a national security reporter.

-

'A Night At The Garden' Reveals Startling Piece Of American History

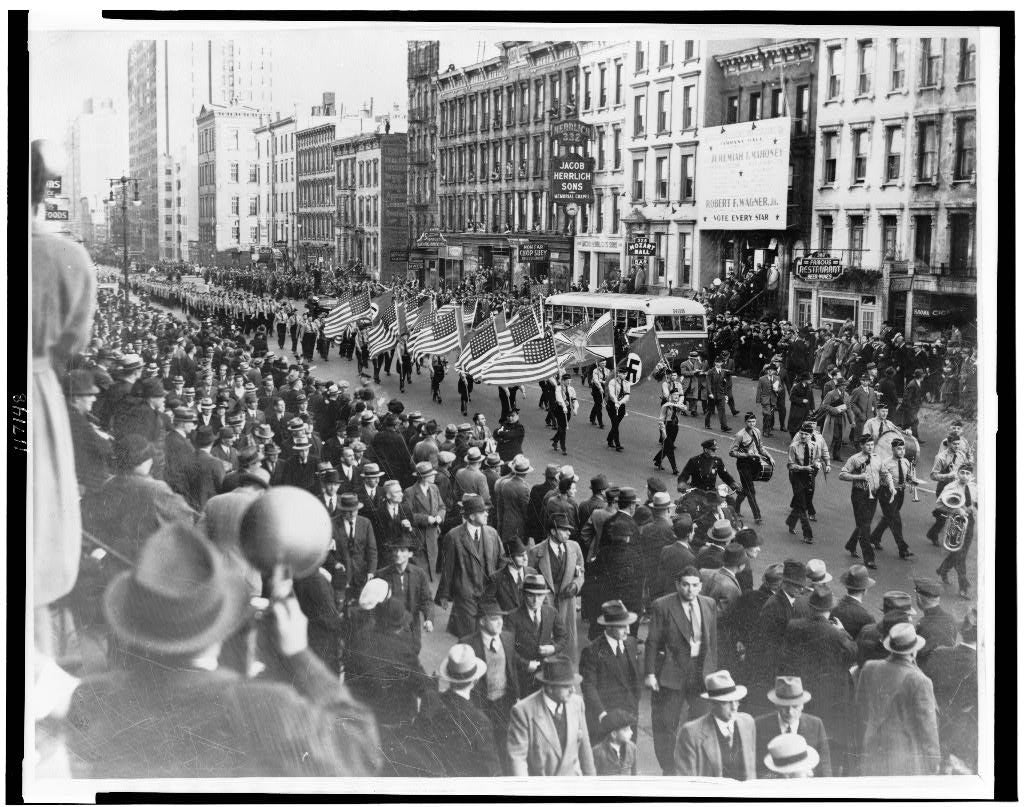

On it’s surface, the Oscar-nominated short documentary film, “A Night At The Garden” looks like something you might see on a big-budget surrealist HBO series, but filmmaker Marshall Curry was shocked when he discovered this slice of horrifying, and very real, American history from the days leading up to WWII.

He was out to dinner with a friend, who told him that in 1939, a gathering of over 20,000 Nazi supporters was held in New York City at Madison Square Garden.

He initially didn’t believe it, “until I got home that night and looked it up,” he said.

He contacted an archival researcher, who found video footage of the event in the archives of UCLA and The National Archives, among others. “So we gathered it, and when I saw it, I just couldn’t believe it,” said Curry.

He was shocked by the scale of the gathering.

“It’s kind of incredible to think that there could be 20,000 Americans, New Yorkers in a pretty progressive city, that would come out to support fascism and anti-Semitism,” he admited. “Unfortunately, when there’s 20,000 that come out for a rally, you know that there are a lot more than that that are supportive, but just couldn’t get a babysitter that night.”

The film starts with an outside shot of Madison Square Garden, and nothing looks particularly out of place.

“Maybe this is going to be about a basketball game,” says Curry. Then we see the marquee, which is promoting a “Pro-America Rally, and so you think, ‘Well, this is going to be some patriotic gathering,’” he continued.

Curry described the event, noting a 30-foot tapestry of George Washington as the backdrop to a large stage. But with a closer look, he said we “realize that there are swastikas on either side. And the thousands of people who are marching in are carrying American flags, but also flags with swastikas.”

The Pledge of Allegiance is recited. The Star Spangled Banner is sung. A man in a uniform resembling a Nazi military officer’s takes the stage to speak from a podium, “and starts attacking the press and demonizing minorities, and eventually a protester runs out on stage and is beaten up,” said Curry.

The protester was arrested. His name was Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old plumber’s helper from Brooklyn. According to The New York Times, at his hearing the following day, the magistrate questioned him, saying, “Don’t you realize that innocent people might have been killed?”

Greenbaum replied, “Do you realize that plenty of Jewish people might be killed with their persecution up there?”

The 7-minute film is presented without narration, additional context or analysis. Curry’s first instinct was to make a more traditional documentary, but on a whim, he tried editing the film without any added explanation. He discovered “It had a real power. It pulled the audience in. As you’re watching this stuff, you’re thinking, ‘What is this? How did this happen?’”

The German-American Bund In Wisconsin

Many of the German-Americans who became activists with the German-American Bund had been in the German Army during the first World War, according to Mark D. Van Ells, who is a Wisconsin native and professor of history at Queensborough Community College in New York City.

“They emigrated to America to have a better life. But when they came, they oftentimes brought their Nazi ideology with them,” he said.

When Hitler took power in Germany in 1933, several small American pro-Nazi groups combined into what was referred to the “Friends of New Germany.” This Nazi-affiliated group didn’t sit well with the American government, so the group re-branded as the Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, or German-American Bund.

As Van Ells explained, “This new organization was not affiliated with the Nazi Party, at least officially. Membership was limited to American citizens, so there were no foreign nationals in the organization. But, of course the organization still kept its’ pro-Nazi sympathies.”

In an essay Van Ells wrote in 2017 on the subject, he explains that the strategy of the Bund in the U.S. and Wisconsin in the 1930s was to infiltrate more traditional German social and business organizations in order to spread its agenda.

At first, groups in the Milwaukee area belonging to the Wisconsin Federation of German-American Societies tried to simply ignore the Bund. But when the Bund became more publicly visible, and targeted Federation members with threats and intimidation, “It led to an open break among German-Americans” in the Milwaukee area, Van Ells explained.

In the summer of 1937, an increasingly bold Bund opened Camp Hindenburg on the banks of the Milwaukee River near Grafton, Wisconsin. A majority of the camp’s attendees were the children of area Bund members, and although “The Bund liked to portray it as the equivalent of the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts,” Van Ells said they were “also learning about Nazi ideology, so it was remarkably like the Hitler Youth back in Germany.”

Photo courtesy of Library of CongressWith the shifting political climate of the late 1930s and America’s eventual entrance in to WWII, the Bund’s influence diminished. The Federation of German-American Societies applied increasing political and social pressure to the group in Wisconsin, and took over the lease to Camp Hindenburg in 1939, followed by claims from the Bund that the camp had been “stolen.”

As Van Ells states, “By 1941, the Bund was really on the ropes. It was after the second World War begins in Europe that the Bund really begins to show a very sharp decline.”

When comparing the political climate at the time of The Bund’s rhetoric to the current atmosphere, Van Ells is reminded of “the main character in one of those slasher movies. Just when you think you’ve gotten rid of them, the killer always pops up from under the bed or out of the closet.” He thinks that in the 1930s, it was the great depression. In the 1950s; the rise of communism.

He continues, “Today’s discussions about immigration have brought up many of those feelings and have brought many of these right-wing groups back out in to the open more.’

Episode Credits

- Rob Ferrett Host

- Judith Siers-Poisson Host

- Natalie Guyette Producer

- J. Carlisle Larsen Producer

- Brad Kolberg Producer

- Yasmin Khan Guest

- Dan Lamothe Guest

- Marshall Curry Guest

- Mark D. Van Ells Ph.D. Guest

- Brad Kolberg Technical Director

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.