On some of Wisconsin’s roads, law enforcement are using AI-powered cameras to photograph cars. And some communities are concerned about the cameras’ use as a powerful government surveillance tool and their potential for misuse.

In addition to reading license plates, these cameras — made by the company Flock Safety — can also register car color, make and model, stickers, damage and other identifying characteristics. That information is uploaded to a database that can be accessed by police departments and federal agencies nationwide.

Last month, the Verona Common Council voted not to renew their contract with Flock after receiving a flood of public comments opposing the cameras. Council President Mara Helmke said that residents pointed to a lack of transparency around how the cameras were being used.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We don’t have any markings around our community that say, ‘You are going to be on camera,’” Helmke told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “Effectively, there is no way in and out of the city without being tracked. And there was no consent around that.”

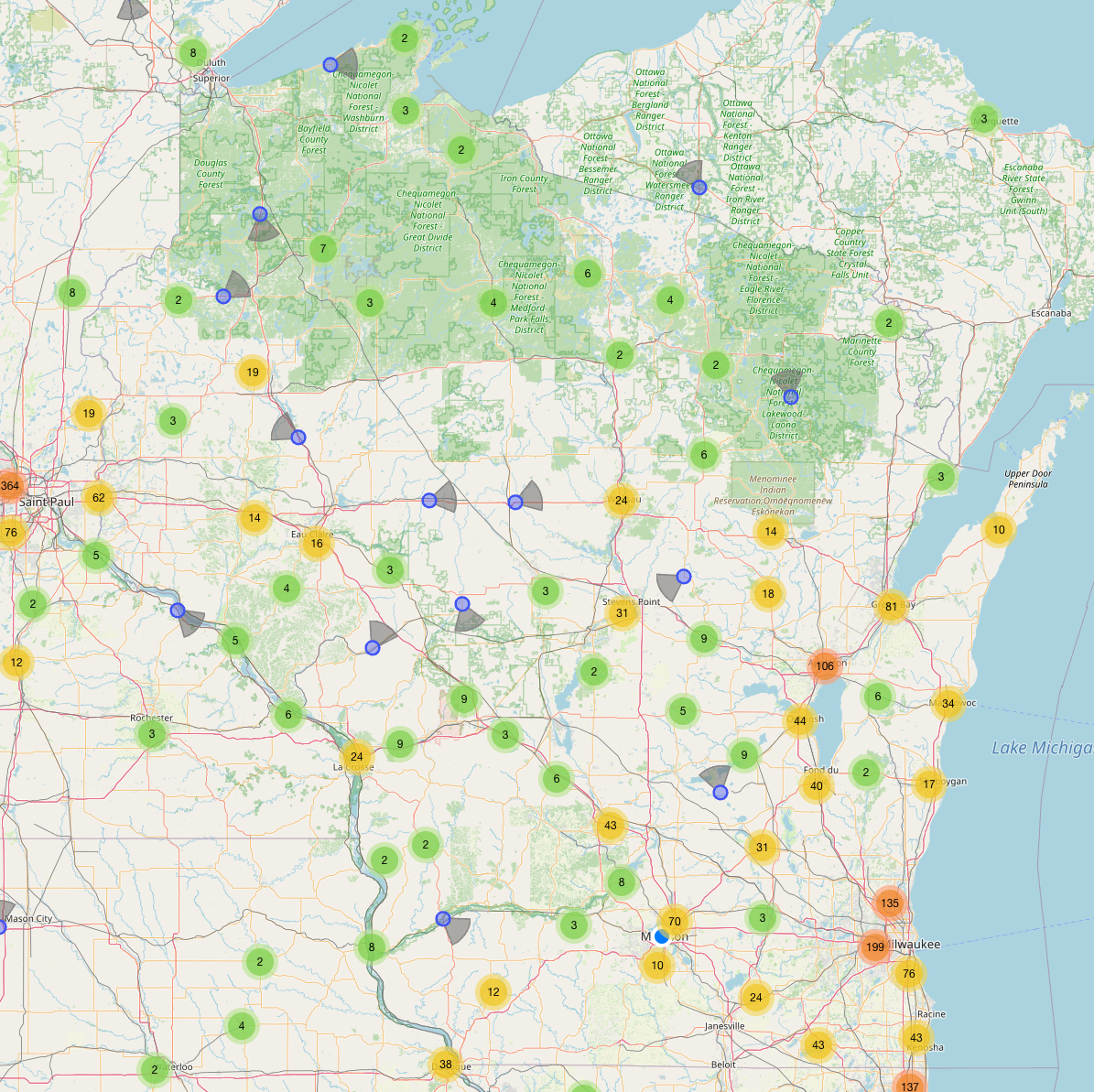

This year, at least 221 Wisconsin law enforcement agencies used Flock cameras, according to an investigation from the Wisconsin Examiner.

The Beaver Dam Police Department was an early adopter of Flock cameras; they first piloted the program about five years ago. They now have at least 12 cameras throughout the city.

Detective Daniel Kuhnz said that Flock allows his department to more efficiently track down cars involved in crimes and other incidents.

“Flock has become an integral part of our tool belt,” Kuhnz said. “It’s essentially eyes out there on the street for us, looking for particular vehicles.”

Flock cameras evolve into an AI-powered nationwide network

License plate readers have been used by law enforcement agencies for decades. What’s new about Flock’s system is the function to share information across agencies nationwide and, more recently, the use of AI.

Flock can now use AI to identify and search for cars by features beyond a car’s license plate, like its color, identifying marks or stickers. It can also notify agencies when flagged vehicles move between jurisdictions.

In Beaver Dam, Kuhnz said, the cameras can help law enforcement find vehicles that are involved in local crimes, or tied to missing or endangered persons. Without Flock, Kuhnz says officers would have to be driving around actively looking.

Officers don’t need a warrant to search for a car in the Flock system. However, they must enter a reason for searching the system.

“We go in and do a random audit of various searches … so that it’s validated as being a legitimate search,” Kuhnz said.

Flock also notifies the police if a car on a “hot list” — one that’s been flagged for criminal activity — enters the city from another area.

“It allows us to proactively respond to crimes before they occur (in Beaver Dam),” Kuhnz said.

Departments can choose whether to share their Flock data with other agencies. But Kuhnz said the sharing is an integral part of the system.

“By the time a crime is committed here and the person flees, they can hop on the highway and be gone within 5-10 minutes and be a needle in a haystack,” Kuhnz said.

City of Verona votes not to renew Flock contract

Many of the comments heard by the Verona Common Council expressed concern about Flock’s use — and potential for abuse — as a government surveillance tool, especially under the Trump administration.

“There are people in our community that are potentially at risk, that would not have been at risk prior to this administration,” Helmke said.

At a Nov. 10 Common Council meeting, multiple citizens expressed concern about people being targeted by federal agencies for their immigration status or for seeking abortion care. Verona resident Gehring Abbattista pointed out that the government could track people based on their political beliefs using their bumper stickers.

At the November meeting, Verona Police Chief Dave Dresser said his department had opted out of data sharing with federal agencies. Verona Alder Beth Tucker Long said the city’s Flock system was searched 974 times by federal agencies in October alone, showing what she said is a lack of integrity from the company.

Lt. Dustin Fehrmann with the Verona Police Department said nearly all of the federal searches from October seem to be from the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, the law enforcement arm of the U.S. Postal Service. He said it’s not clear why that agency seems to be an exception.

“I think the number of access points of this data is really jarring,” Helmke said. “For a community the size of Verona, it does not make sense quantitatively why we or any other community would be targeted to that degree.”

Plus, Helmke saw issues with the documented justification for system searches.

“Much of it seemed unjustifiable — not legitimate reasons. Reasons that weren’t aligned with public safety,” Helmke said.

Jon McCray Jones, policy analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union, said Flock is ripe for abuse. According to the Wisconsin Examiner investigation, officers can and do input vague reasons for searches like “investigation.”

Jones said individuals could easily use the system for personal gain. In other states, there have been cases of officers using automated license plate cameras to stalk and harass private citizens. In Wisconsin, City of Greenfield Police Chief Jay Johnson was charged last month with allegedly ordering the installation of a police surveillance camera outside his home for personal reasons related to his ongoing divorce.

“I don’t believe that most law enforcement agents are misusing surveillance technology,” Jones said. “But if you have thousands and tens of thousands of searches going on, you only need one percent to have major problems.”

Plus, Jones said, Flock poses a major threat to cybersecurity. He pointed to an investigation by 404 Media and WIRED Magazine that found that Flock uses workers in the Philippines to train its AI using real images from communities in the U.S.

“Once that data gets out of local control, we don’t know where it goes,” Jones said. “The best way to stop this data from getting out is just not collecting it in the first place.”

ACLU of Wisconsin encourages community control over police surveillance

According to Jones, cities like Verona are walking back their Flock camera program because the safety benefits aren’t worth trading for their citizens’ privacy.

“Long-term studies of (automatic license plate reader) installations show inconsistent effects on crime rate,” Jones said. “Until we have clear, independent data that license plate readers are actually preventing crime, I don’t believe that the trade off for privacy is worth it.”

Jones said to mitigate the issues with Flock cameras in the state, the ACLU of Wisconsin wants better public reporting on all Flock searches — including precise and detailed documentation on justification and outcomes.

The ACLU also wants to stop data sharing with agencies outside the state of Wisconsin and to introduce “sunset clauses” that require legislators to regularly reauthorize the use of Flock cameras.

Jones said more than anything, he’d like to see communities have control over police ordinances passed at the local level and beyond.

“It allows community leaders, private citizens and elected officials to have the conversation and come to a decision on what privacy is willing to be exchanged under the guise of safety,” Jones said.