Wisconsin governors would see one of their most unique veto powers weakened under a proposed constitutional amendment that passed the state Assembly Tuesday.

The partial veto power — in which a governor can cross out words, numbers or punctuation from an appropriation bill — could not be used to create or increase taxes or fees, according to the proposal.

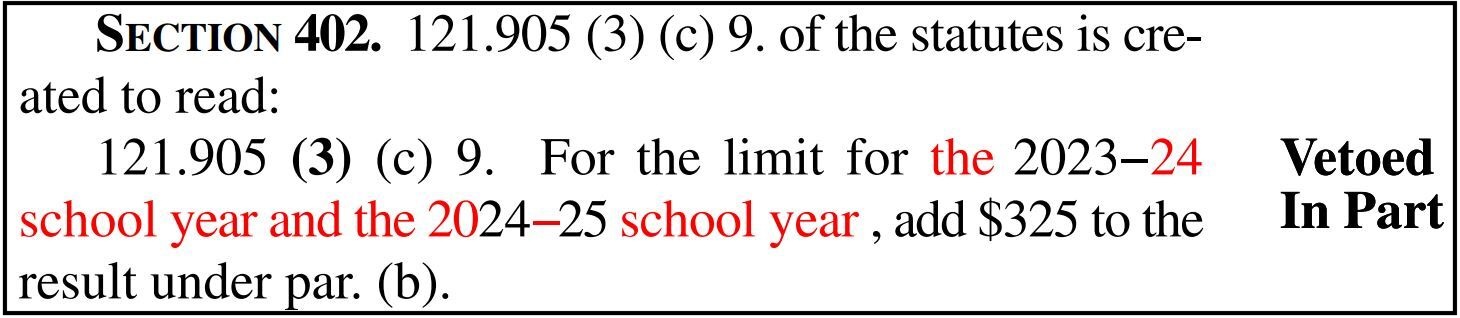

The plan comes months after Gov. Tony Evers made national headlines when he used his partial veto to cross out some words, numbers and punctuation in the budget passed by Republican lawmakers to extend school funding for 402 years — up from the two years that had originally been intended.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

During Assembly debate Tuesday, the bill’s author, Rep. Amanda Nedweski, R-Pleasant Prairie, argued that defanging the partial veto would uphold the separation of powers between the legislative and executive branches.

“When Gov. Evers used the partial veto to institute a 402-year tax increase on the hard-working people of Wisconsin, he was lauded by some as a genius,” she said. “If this had been done by Gov. (Scott) Walker … the same people would be triggered into dramatic meltdowns of injustice.”

Both Republican and Democratic governors have wielded their veto pen in a variety of ways. Walker, a Republican, used the partial veto to make one state program last indefinitely, in what was termed a “thousand-year veto.”

Fellow Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson used what was then known as the “Vanna White veto” to piece together letters from different words to create new words, a practice that was eventually banned. And Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle used a “Frankenstein veto” — another practice ended by voters — to move more than $400 million out of the state’s road fund to pay for schools instead.

Even though it’s not as broad as it used to be, the partial veto of a Wisconsin executive is unique among states. While 44 states have some form of a line-item veto, only Wisconsin has the partial veto, which gives governors more freedom to carve up spending bills.

Nedweski told Democrats they should think about whether they’d support that if someone other than Evers were governor.

“The bottom line is the governor is not a Legislature and should not be abusing the partial veto to act as a legislator,” Nedweski said.

The plan passed on a 64-34 party line vote and heads next to the Senate. No other lawmakers spoke during debate.

As a proposed constitutional amendment, the plan would need to pass the full Legislature in two consecutive sessions before it can be brought to voters for approval.

It has support from the conservative groups Americans for Prosperity, Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty and Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, and is opposed by the Wisconsin Education Association Council.

Republicans pass restrictions on where homeless people can camp

The state Assembly also approved a bill that would withhold funds for state homeless services unless they meet certain benchmarks and criminalize sleeping on public property unless it has been designated as a temporary campground.

The bill would withhold portions of state grants aimed at fighting homelessness contingent on performance outcomes. Grant recipients would have to demonstrate that they have increased the number of homeless people who have found housing and work, and decreased return to homelessness after participation.

It would also create a criminal penalty for people living outdoors on public property unless the state Department of Administration has designated it a “structured camping facility.” Those facilities would have to offer water and sanitary facilities, and mandatory mental health and substance abuse screenings, although the bill does not designate funding to create those programs or services.

People who sleep in non-designated public places could be subject to a $500 fine or 30 days in jail, unless “the person has no other reasonable options or would be denied admission to a homeless shelter due to its being at capacity.”

Republicans argued the bill will increase accountability for public programs that seek to address homelessness, and it will move homeless people into safer spaces.

“What we’re doing now isn’t working. We should look at the money that we’re spending in these areas making sure that the that it’s going towards something that’s successful,” said Rep. Alex Dallman, R-Green Lake, the bill’s lead author.

“There’s nothing more inhumane than allowing a population of homelessness into homeless individuals to live on our streets and on our sidewalks on the front steps of our businesses. Let’s get them to an area where we can help them.”

Democrats called the proposal cruel and said it would do nothing to alleviate homelessness. Rather, they argued, it would criminalize homelessness and force people with limited means into a cycle of fines and incarceration.

“You’d be making it more difficult for people who are looking for housing, trying to be safe to find housing and be safe,” said Rep. Mike Bare, D-Verona. “You’d be dehumanizing people, traumatizing them, causing them unnecessary interactions with law enforcement, who frankly have better things to do.”

The plan passed 60-39, with four Republicans joining all Democrats in voting against it.

The bill is opposed by anti-poverty groups and public health groups, the Wisconsin Catholic Conference, the ACLU, the City of Milwaukee and Dane County, among other groups. It is supported by Cicero Action, a Texas-based group that drafted the model legislation upon which this bill was based.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.