In the dark, dungeon-like basement of Birge Hall at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, researcher Guilherme Gainett examined a tiny arachnid under a microscope and jumped from his chair in excitement.

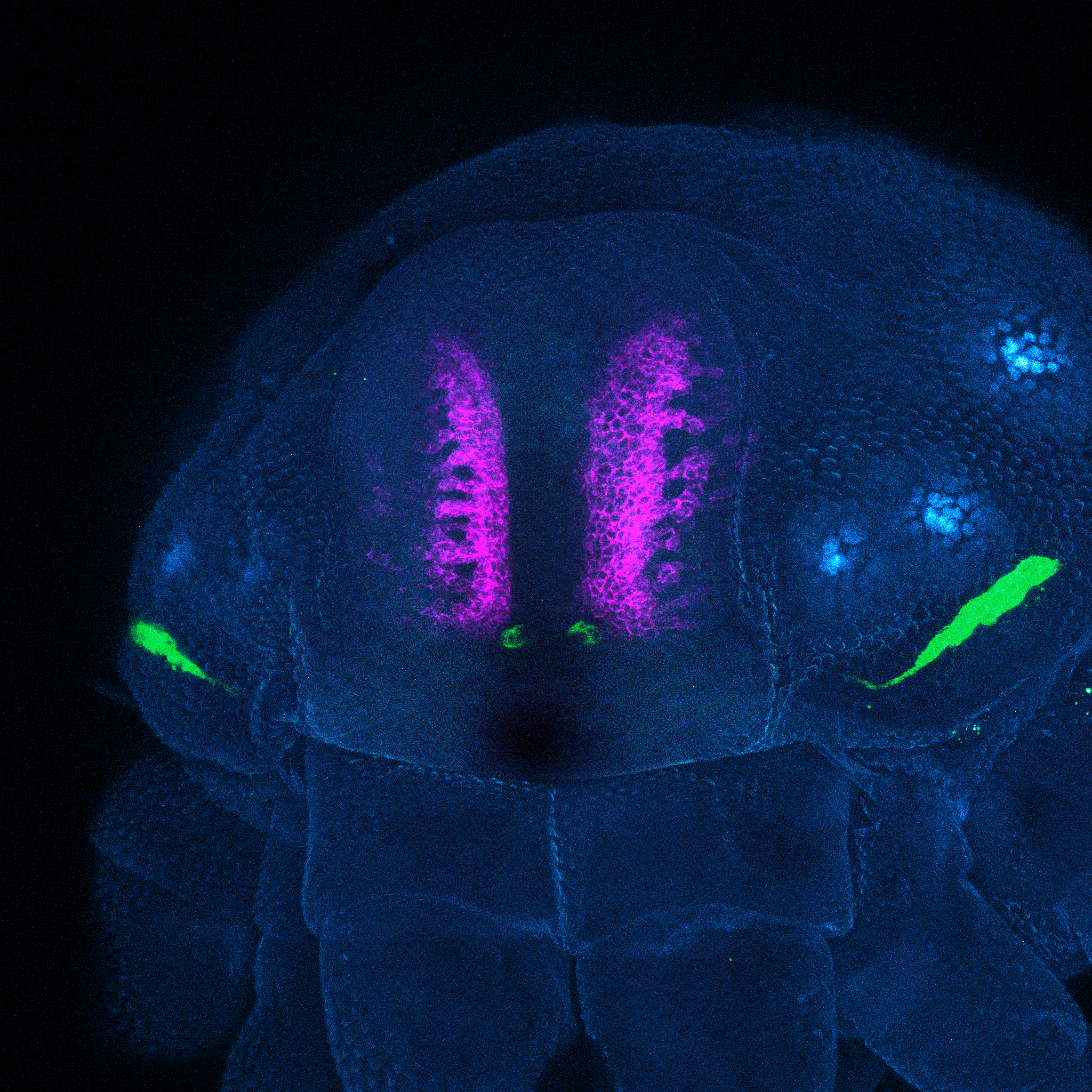

The illuminated species of daddy longlegs appeared to have four more eyes than scientists had previously documented. Gainett called for his colleague, associate professor of integrative biology Prashant Sharma, who confirmed the finding and was shocked.

“That was a very interesting and serendipitous discovery,” Gainett said. “One of the happiest moments of my life as a scientist.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Gainett and Sharma recently appeared on WPR’s “The Morning Show” to discuss the breakthrough from 2022, which was recently published in the journal “Current Biology.”

Sharma said the discovery reminded him of a 305-million-year-old arachnid fossil with multiple eye pairs that was found a decade ago .

“The understanding for the entire body of literature since Western civilization has known about daddy longlegs is that they only had one eye pair,” Sharma said.

Daddy longlegs are relatives of spiders in the arachnid family. While spiders can spin silk and carry venom in glands, daddy longlegs lack those features, Sharma said.

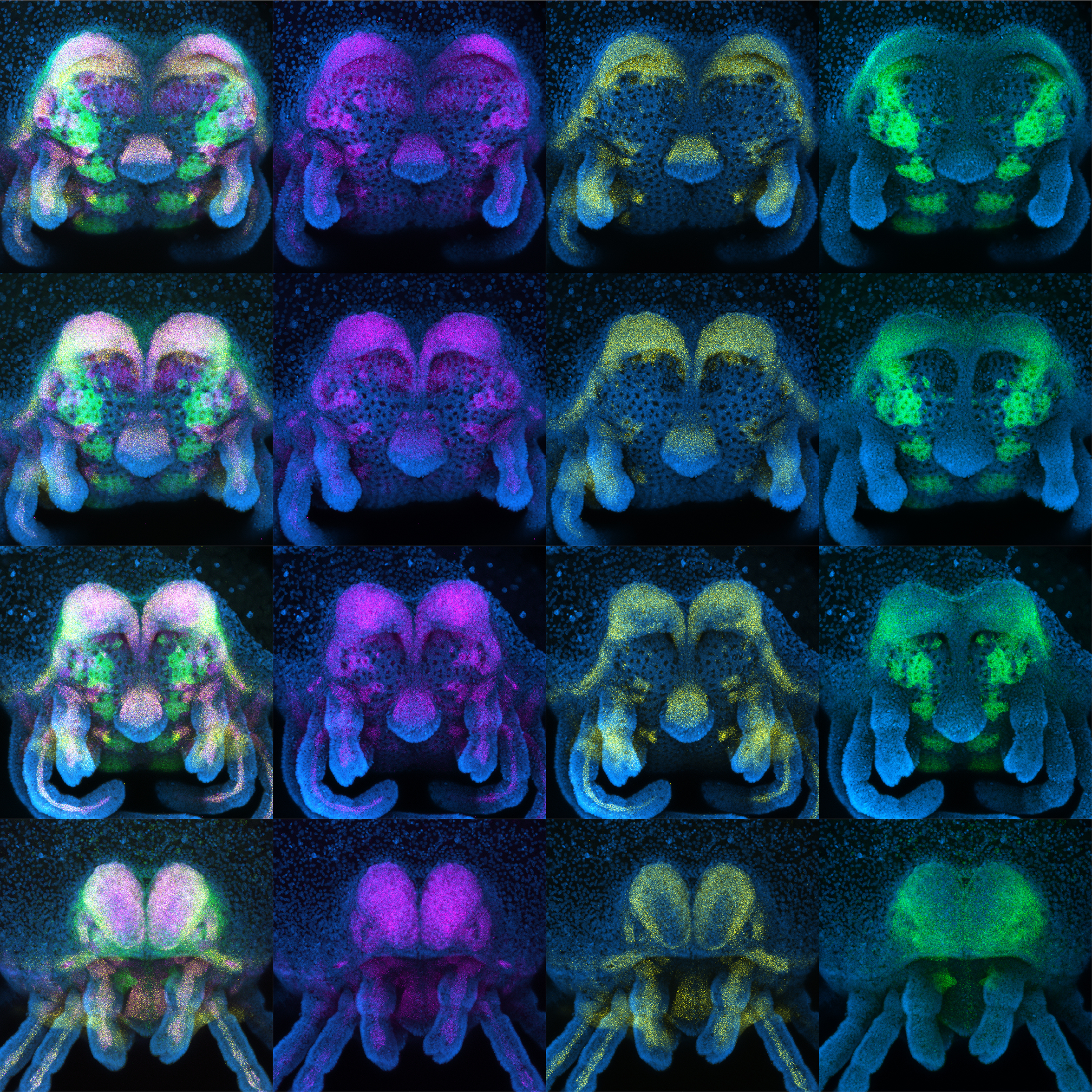

In the lab, Gainett’s excitement came when he looked at the daddy longlegs’ embryo and saw opsins, which are proteins needed for vision. But it appears the extra eyes are unable to actually see.

After getting his doctorate in integrative biology at UW-Madison in 2023, Gainett moved on to a post-doctoral program at Harvard Medical School. He said researchers are still studying the eyes of daddy longlegs, so it’s possible the extra eyes serve some function.

Learning the existence of additional eyes on daddy longlegs could help scientists understand the evolution of arachnids. They thought the 305-million-year-old fossil was related to a group with tiny legs. Gainett said the new discovery suggests the fossil is more closely related to a species with long legs and daddy longlegs are 50 million years older than previously thought.

“That shifts the family tree of this entire group and all our estimates of how old the group is,” he said. “This has a lot of downstream implications. For example, that pushes the age of this group to a different geological age, the Devonian.”

Scientists have identified about 6,500 species of daddy longlegs. After Gainett and Sharma’s discovery, Gainett traveled to his native Brazil to see if their findings came up in daddy longlegs elsewhere. He similarly found remnants of lateral eyes, suggesting this discovery of extra eyes could apply to more than one species of daddy longlegs.

“We do think this is widespread in the group,” Gainett said. “It’s just opening a window to investigate this right now.”

Gainett wants to keep studying the evolution of arachnid eyes. How did the change happen? Which genes changed?

“There are certainly more questions now than answers, as usual with science,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.