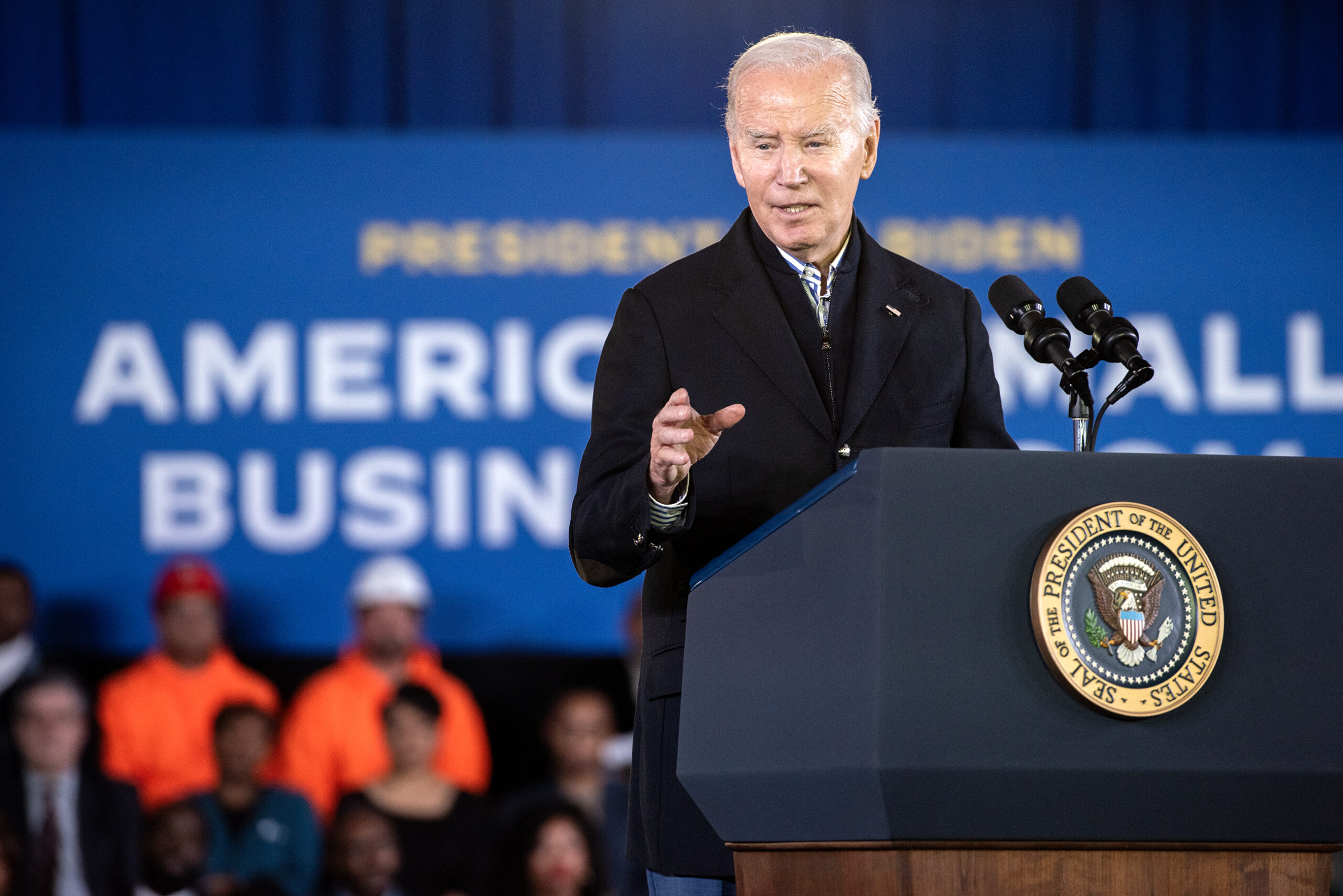

Two days after President Joe Biden ended his campaign and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris, she could have gone anywhere to hold her first big presidential campaign rally. She chose Wisconsin.

Two weeks later, when Harris was trotting out her newly minted running mate, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, she announced a tour of swing states. Wisconsin was one of the stops.

“Oh, it really is good to be back in Wisconsin,” she told the large crowd in Eau Claire. “The path to the White House runs right through this state. And with your help, we will win in November.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In politics, it’s hardly unusual for candidates to engage in flattery as they make their way from one swing state to the next. But the frequency of Harris’ Wisconsin visits, and Biden’s before her, underscores the importance Democrats are placing on the state.

It’s a sentiment many voters understand keenly in Wisconsin, where the previous two presidential elections were decided by about 20,000 votes. In 2020, Wisconsin went to Biden. Four years before that, it was carried by former President Donald Trump.

There were many factors at play in 2016, but for some Democrats, one truth looms large. That year, then-Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton didn’t come to Wisconsin at all.

The legacy of what happens when you take Wisconsin for granted is an enduring one. Now, it’s animating a full-scale battle for this battleground state.

This week, even as the Democratic National Convention is taking place in Chicago, the Harris campaign plans to hold a rally in Milwaukee on Tuesday. It will be Harris’s seventh visit to Wisconsin this year.

“There’s become a sort of article of faith, kind of chiseled somewhere on the tablet of Democratic commandments,” said Sam Munger, a veteran Wisconsin Democratic policy expert. “‘Thou shalt not forget Wisconsin,’ because of what happened with Hillary.”

Wisconsin a key part of ‘blue wall’ for Democrats

Alongside Michigan and Pennsylvania, Wisconsin is part of what Democratic strategists call a “blue wall” — a kind of fortress of must-win swing states that protect their projected path to the White House.

Of those states, Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes give it the smallest share of the electoral college, but its historically small presidential margins and divided electorate give it outsized importance in national elections, said John Nichols, a progressive journalist from Madison who has written books about the state’s politics.

“Coming to Wisconsin, campaigning hard, figuring Wisconsin out, figuring out how to win — it becomes a very critical requirement if you are trying to win the battleground states,” he said. “Oddly, because Wisconsin is so frequently close, what that means is that if you do figure out Wisconsin, if you figure out how to campaign effectively in Wisconsin, you tip the balance.”

For decades, Democrats prioritized the Badger State. Al Gore and John Kerry ultimately lost their White House bids in 2000 and 2004 respectively, but both fought for, and narrowly carried Wisconsin. Former President Barack Obama swept the state twice, winning relative landslides in a state usually won by less than a percentage point.

Nichols said he remembers the night of the 2016 election, when Trump outperformed expectations and was declared the winner in states that Democrats thought they had in the bag.

“Democrats, up to that point in 2016, they were saying, ‘Well, you know, wait for Wisconsin. Wisconsin will clean up a lot of this mess,’” he recalled. “When Wisconsin was clearly lost, then you sort of had desperate calculations.”

The memory of that night haunts Democrats, locally and nationally, and they are determined not to make the same mistakes.

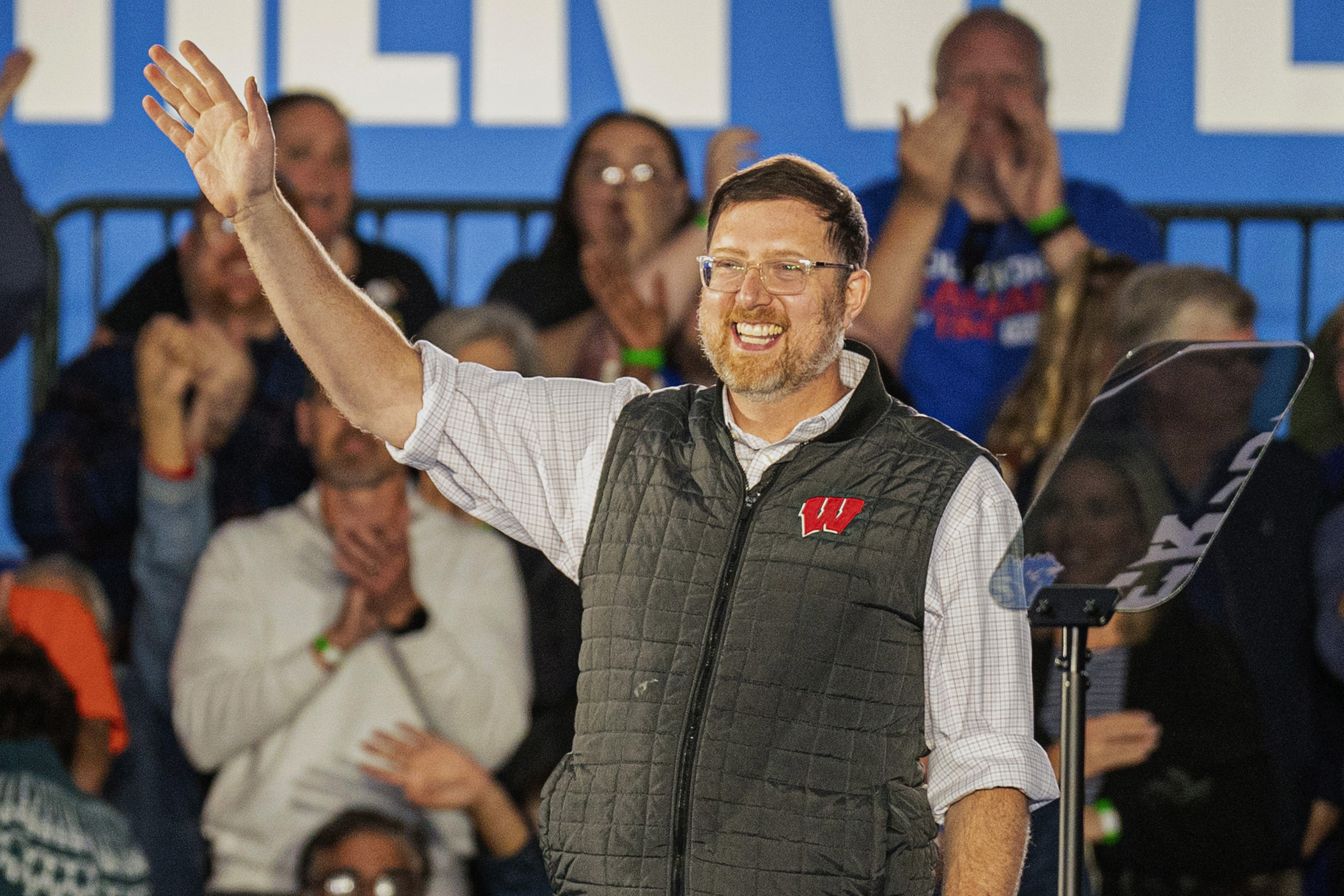

That extends far beyond candidate visits, and animates a volunteer ground game that has been in the works for years, according to Wisconsin Democratic Party Chair Ben Wikler. In short, he said, they’re campaigning as though Wisconsin will be the tipping point for the entire country.

“Elections here are often within the margin of effort,” he said. “When it goes well, there’s a real sense of, ‘We did that. It might not have happened if we hadn’t done everything we could.’”

Voters and volunteers feel the urgency

In 2020, Biden clawed Wisconsin back, but the circumstances of that campaign were unique.

Democrats had planned a Wisconsin-centric campaign when they chose Milwaukee to host the Democratic National Convention that year. But due to COVID-19, that year’s DNC became a mostly virtual event.

Democrats also followed COVID-19 protocols that prohibited door-knocking and other face-to-face tactics, a massive change to their typical ground game.

Because of that, this is the first year the party has had a chance to implement the lessons of 2016 using more traditional strategies to connect with voters, said Wikler. That includes hosting small-scale events like bingo nights and block parties.

On a recent windy Saturday in Milwaukee’s Washington Park, a couple dozen residents ate mac and cheese and collard greens as U.S. Rep. Gwen Moore, D-Milwaukee, urged them to get involved in this year’s campaigns.

“We were devastated when Trump won in 2016 (and we) barely won in 2020 so we’re not taking anything for granted,” she told WPR. “We understand that every single vote counts, that every single registration counts.”

Jaliah Jefferson, a Democratic party organizer, said events like these are key to wringing out the small number of votes that could be the difference between victory and defeat.

“Every packet that someone knocks and every voter that someone talks to, really could be the difference between us winning and losing,” she said.

Jefferson, who works from one of 48 storefront-style Democratic field offices across the state, said the memory of 2016 — and a sense that too many Democrats took the state for granted — motivates many of her volunteers.

“People, a lot of the times, they come into the office and they say they want to get involved, because they know that they could have done more in 2016 and then they saw the result of that,” she said. “We have people come in and they say, ‘I don’t want this to be a repeat. What can I do to help?’”

For both parties, campaign strategy mixes with political symbolism

But just winning Democratic strongholds isn’t enough, said Nichols, the political journalist. Clinching the state can come down to a handful of votes in each ward, and both sides know it.

Republicans understand the importance of Wisconsin just as acutely. That’s partly why the Republican National Convention took place in Milwaukee last month. In his speech accepting his party’s nomination, Trump even joked about trying to “buy” Wisconsin votes by investing in the state.

“If Democrats know they need to win Wisconsin, Republicans know they need to win Wisconsin,” said Andrew Iverson, the executive director of the Republican Party of Wisconsin. “It all comes down to this state.”

The Trump campaign has also maintained a steady presence in the state this year. Prior to the RNC, Trump held rallies in Waukesha and Green Bay. His running mate, JD Vance, was in Eau Claire on the same day as the first Harris-Walz visit, and campaigned in Milwaukee Friday.

Republicans also have a ground game that involves frequent community events and 30 storefront field offices. The state party recently celebrated the opening of an office in a largely Latino part of Milwaukee, an effort to make inroads with a voting bloc that skews Democratic in a heavily-Democratic city.

“We have to perform a little bit better than we have traditionally in Democrat strongholds. We also need to perform well in traditional Republican strongholds,” Iverson said. “There isn’t one or two areas that we can just fully focus on. We need to do well in every single corner of the state.”

Beyond the electoral college math of winning Wisconsin, both parties also see a symbolic victory in clinching Wisconsin.

For Republicans, 2016 was the first time they’d won Wisconsin since 1984, when President Ronald Reagan was ushering in a new brand of conservative politics, telling voters it was “morning in America.” A little white house in Ripon, Wisconsin, claims to be the birthplace of the modern GOP.

For Democrats, each Wisconsin victory is a reminder that progressive politics are alive and well in a state where policies like union rights, workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance are woven into its history.

“Wisconsin’s identity is built around the idea of progress,” said Wikler. “Our state motto is ‘Forward.’”

To reach voters here, both campaigns will need to appeal not only to voters’ preferences on policy, but to their sense of urgency. Regular candidate visits are one way to drive that urgency home.

“I think there’s real good strategic reasons to come to Wisconsin. It’s about math. It’s about symbolism. It’s about the Electoral College and how few states are really at play,” said Munger, the Democratic policy expert. “I also think no Democrat will ever be allowed to skip Wisconsin again.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.