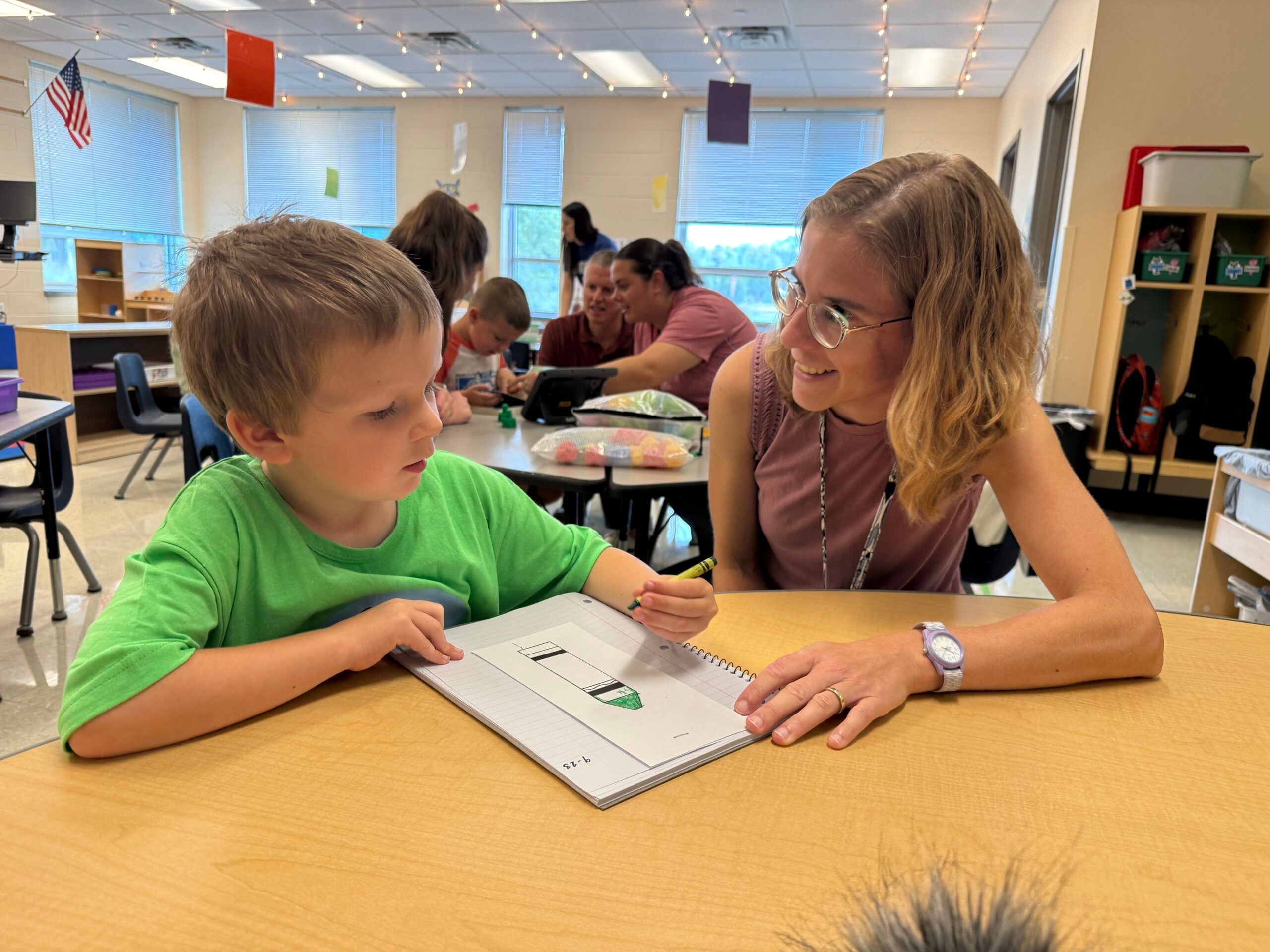

Elizabeth Chandler is seated at a crescent-shaped table at the end of a brightly lit hallway at Bridges Elementary School in Prairie du Sac.

On this school morning, she’s working with two boys in pre-kindergarten on “R” sounds.

“You colored it blue, but the R word was grrrray and we grrrrowl like a dog,” Chandler says.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Grrrray,” one boy responds.

“We’re going to growl again,” Chandler said. “Ready? Grrrr.. Grin.”

Together, they grrrowl and grrrin over and over.

As a speech pathologist, Chandler has used exercises like these for years.

But she’s finding more and more children are in need of her help.

In Prairie du Sac and across the state, educators say young children have been struggling with language development.

Researchers believe that problem could be fueled by increased screen time on phones and tablets cutting down on interaction between babies and their caregivers.

Demand for services has jumped 87 percent in Sauk Prairie

The Sauk Prairie School District has seen a significant increase in referrals for speech and language services for the community’s youngest children over the last few years, said Superintendent Jeff Wright.

Wright and his team believe the increase is due to children and caregivers spending more time on screens.

“When I look into a baby’s eyes and ‘goo goo ga ga,’ and the baby makes those sounds back, that child is learning how to make that hard G sound with me,” Wright said. “But you can’t learn that through a screen. And you also can’t learn that if you see the foreheads of adults more than you see their full faces.”

Parental tech use has been likened to secondhand smoke in that it might endanger children’s health and development in ways we don’t even fully understand yet.

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines screen time as any time spent interacting with digital devices, including smartphones, tablets, computers and televisions.

For children ages 2 to 5 years, screen time should be limited to one hour per day of “high-quality educational programming.”

The academy recommends no screen time for children 18 months or younger, with the exception being a live video chat.

Dawn Merth-Johnson, a speech-language education consultant with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, said adults should also be aware of how often they’re on screens in front of their children.

“A typical guide for adults is, would I be reading a book right now if I were sitting in front of you,” Merth-Johnson said. “Parental tech use has been likened to secondhand smoke in that it might endanger children’s health and development in ways we don’t even fully understand yet.”

While the full extent of how screen time affects a child’s development isn’t fully known, the Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics Edition found that children who were given screens at the age of 1 had more developmental delays in communication and problem-solving at ages 2 through 4 years.

The 2023 study also found that the more hours a toddler was exposed to screen time, the more likely they were to have developmental delays.

The pandemic likely also had an impact. A 2023 survey by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association found that nearly 70 percent of respondents were getting more requests to evaluate young children than before the pandemic.

The children coming in had more emotional and behavioral issues, delayed language development and social communication problems, according to the survey.

In Sauk Prairie, the district of about 2,600, there were 15 children in pre-kindergarten through 4K receiving speech language services in the 2022-23 school year.

This year, there are 28 children in those grades receiving services, an 86.6 percent jump.

Sauk Prairie School District is not alone

In spring 2025, the Wisconsin Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Association surveyed 163 school districts and found that 26 percent had an opening for a speech pathologist.

The American Speech Language Hearing Association has identified shortages in all regions of the U.S., particularly in schools, Merth-Johnson said.

The demand for services is expected to grow by 15 percent by 2034.

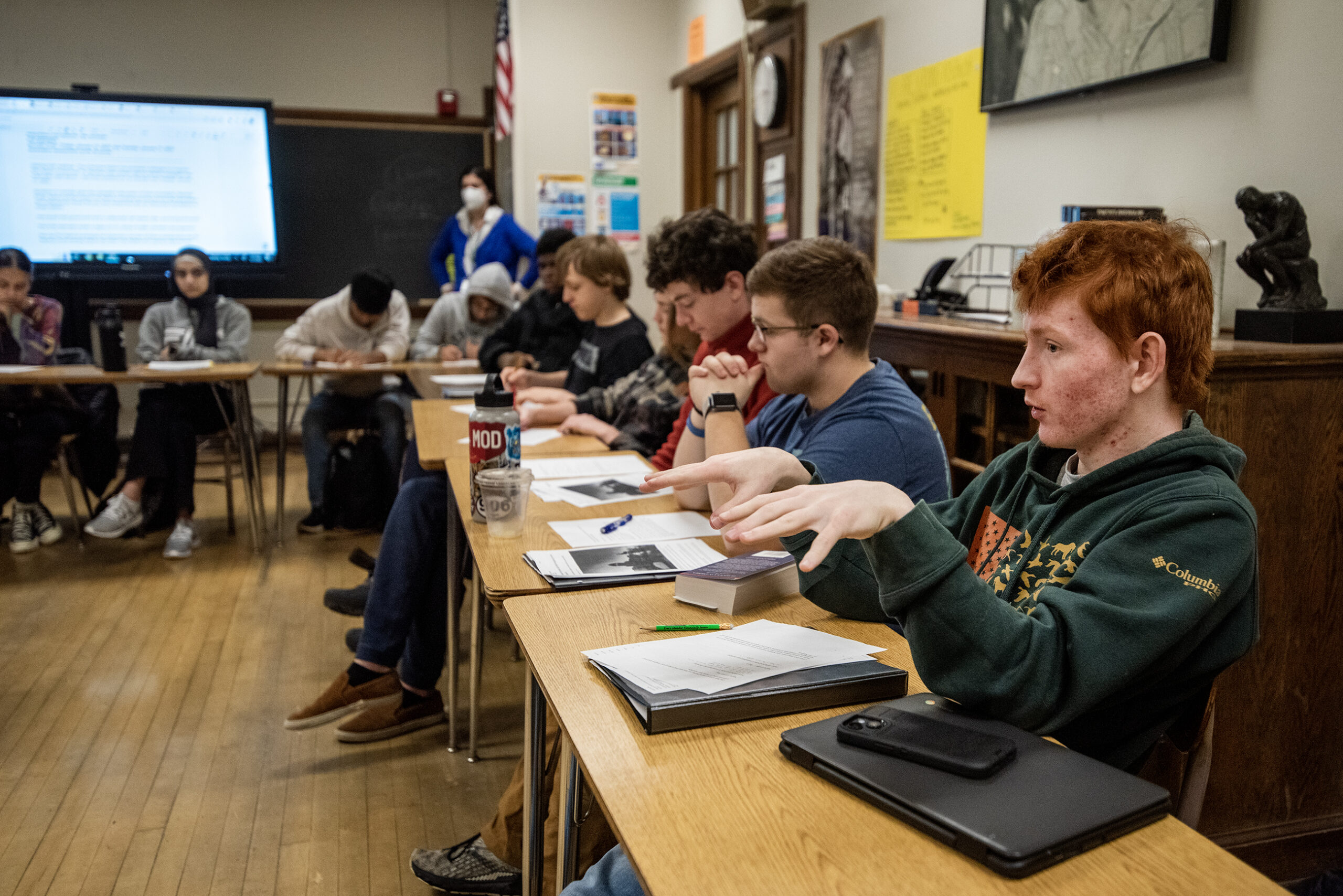

While Chandler works with the young boys on “grrr” sounds in the hallway, a few of her colleagues are in the 4-year-old kindergarten classroom at Bridges Elementary School.

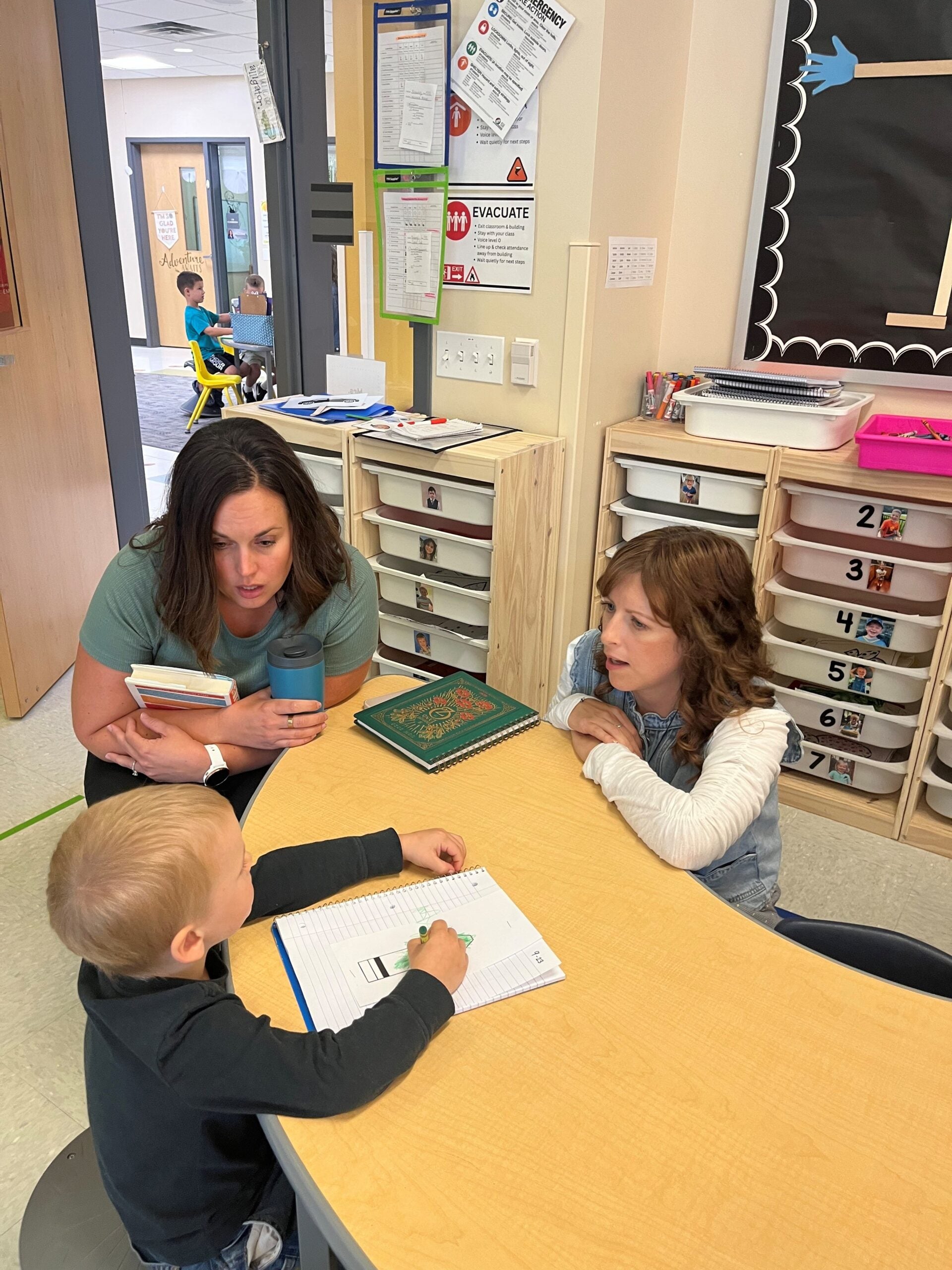

Anna Bina and Alyssa Franciskovich are having a conversation with a boy about the trucks at his family farm.

Bina and Franciskovich correct him gently when he says the trucks dump out “devil,” instead of “gravel.”

Nearby, Alicia Schaefer, another speech therapist, is coloring with a student and having a similar conversation, kindly correcting words.

These conversations about trucks and colors seem simple, but are what speech therapists call “joint attention.”

Bina said having a shared activity to talk about is critical for language growth.

“When children are only getting one side from a screen, it’s different,” Bina said. “It’s more passive than engaged.”

While all of this is happening, the other children in the classroom are playing games while learning numbers.

At one table, a small group uses plastic cups and drawings of peacocks as tools to learn to count.

Wright, the superintendent, said he’s happy that when he walks into the classroom, the children who aren’t in front of the teacher aren’t being occupied by a screen.

“They’re playing in a creative way with household items,” Wright said. “You could play with cups in your house. You could build something or color something. Very simple things.”

The speech therapists all agree that creating games at home is a lot harder than using a screen while trying to make dinner.

They suggest caregivers narrate what they’re doing in front of young children.

“Everyone is doing the best they can,” Bina said. “But when you’re on your phone, you’re not doing some of the things we know would be good. Narrating your child’s play, commenting on what they are doing. Talking with your child doesn’t just mean asking a ton of questions.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.