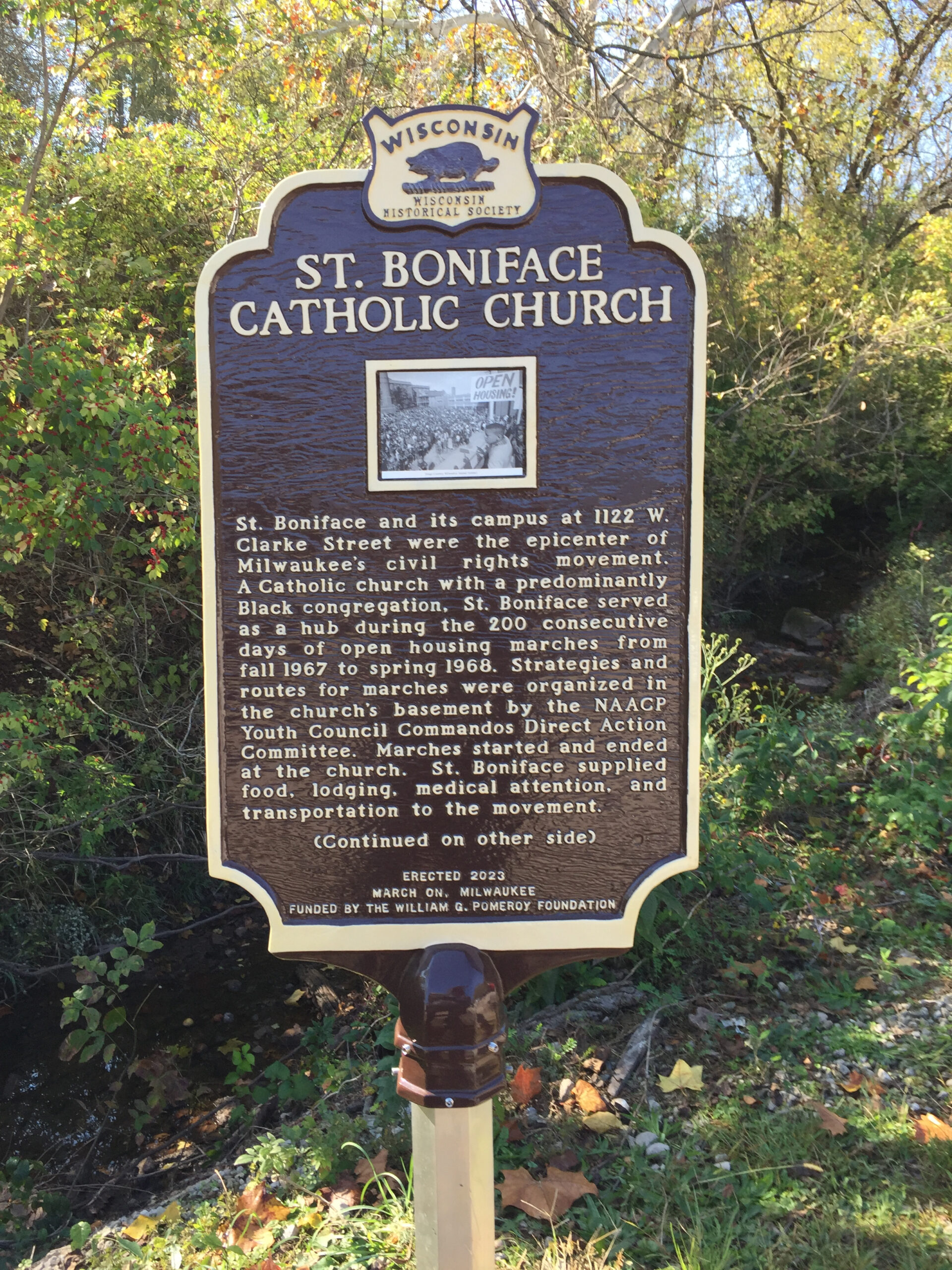

A new state historical marker was unveiled at St. Boniface Catholic Church in Milwaukee to commemorate the city’s fair housing marches. From 1967-68, activists marched for 200 consecutive nights to protest segregation in housing in the city.

This marker is a part of a larger series in partnership with March On, Milwaukee. The group is a grassroots organization of former NAACP Youth Council members and Commandos, community organizers, historians and more.

Four new markers in total will be installed throughout Milwaukee by the spring, while an additional five markers are still in the planning phase.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Robert S. Smith is the director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching and Outreach at Marquette University. He spoke with WPR’s “Morning Edition” host Alex Crowe about the history behind the markers.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Alex Crowe: What sparked these marches and what were the goals of the people involved in them?

Robert S. Smith: The open housing marches of 1967-68 here in Milwaukee really fit in this rich tradition of both civil rights activism and civil rights era protests. And it gets melded with an emerging sense of radicalism as we move into what most scholars or what folks might refer to as the era of Black Power.

So here in Milwaukee, you have the more longstanding efforts of marching, boycotting as a means of demanding basic rights, fundamental rights of citizenship.

And then included in that process is an emerging voice of young people who are less patient and less willing to sit across from folks negotiating, who are then also as young people wanting those rights to manifest immediately.

AC: Why do you think now is the time that these markers are being put in?

RS: I’m not sure why now. But I am certain that it’s been a community-wide call for the full recognition of the significance of the open housing marches. And the marchers to be not only recognized as important civil rights activists and figures, but today presents the opportunity for these conversations to be included in our classroom curricula.

So I guess a more concrete response is that it’s been several decades in the making. There’s been a community-wide swelling of voices to highlight how important this history is. And we’re really lucky to have had some of those marchers involved in that process along the way.

The more that we are engaging those histories with more identities, the more enjoyable it will continue to be.

Robert S. Smith

AC: These historical markers commemorate Black history in Wisconsin, but of those more than 600 historical markers in the state, only 10 commemorate the history of the state’s Black residents. Ten represent women’s history, but there are none that represent the state’s Hmong, Hispanic or LGBTQ+ communities.

What would your message be for people in those communities who are looking to get more representation themselves?

RS: As a member of the Board of Curators for the Wisconsin Historical Society, these are the very kinds of questions that we are raising on a regular basis. To be perfectly honest, though, we’re in a different moment today than we were 10 years ago, 20 years ago — where, as we’ve seen over the last couple of years, the very question of what gets memorialized and how it gets memorialized has moved decidedly into the hands of grassroots voices. And that’s not only being determined by our more longstanding institutions that were quite honestly dominated — overwhelmingly — either by European histories and/or white histories, if you will.

Now we are just simply at a place where this very fundamental conversation around the public representation of history — folks are demanding quite a bit more inclusion.

You know, I don’t mean to overly lighten the mood, but history is also fun. And the more that we are working to engage and include more voices, more diverse identities, our young people and people in general will also see themselves in those histories and begin to or continue to enjoy those histories. Because they are more inclusive.

History is also so much about identity. And the more that we are engaging those histories with more identities, the more enjoyable it will continue to be.

You can hear an extended version of this conversation on Wisconsin Today.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.