A few weeks ago, on a University of Wisconsin-Madison campus sidewalk, a message in chalk read “DIVEST from Militarism.” It was final exams week, students and older adults alike lounged, studied and conversed alongside tents pitched illegally in protest, while a dainty melody on solo clarinet could be heard playing.

Students in Wisconsin and around the country protesting the war in Gaza, Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, and U.S. involvement, have included in their demands that the academic institutions they’re part of cut financial ties and withdraw investments from Israeli institutions and Israel-aligned companies.

UW-Madison students reached a deal with the university, campus administrators announced May 10, that included removing tents in exchange for getting to meet with the boards managing the school’s endowment.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Student calls for divestment actually go back decades in Madison’s history.

In 1969, a group of UW-Madison students formed the Madison Area Committee on Southern Africa, or MACSA, to raise awareness of humanitarian issues colonized people were facing in multiple countries, including Namibia and South Africa.

MACSA also promoted boycotts of companies that did business with South Africa, and the group pressured UW-Madison to divest its holdings of securities and stocks in the country.

William Minter was a prominent member of MACSA in the early 1970s. He earned a doctorate in sociology and African Studies at UW-Madison, following two years teaching in the school of the Mozambique Liberation Front in Tanzania. Minter is now an activist and scholar on Africa, editing a Substack blog called AfricaFocus Notes.

He recently told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” one of the reasons UW-Madison was such an early hotspot for anti-apartheid sentiment and action was its excellent African languages and literature programs.

“Among the scholars attracted to that were exiled South Africans Daniel Kunene and his wife, Selina, and A.C. Jordan and his wife, Phyllis,” Minter said. “These (Daniel Kunene and A.C. Jordan) were two of the most distinguished scholars and linguists of Black South Africa. They were in exile, but were going to do what they could to support the struggle back home.”

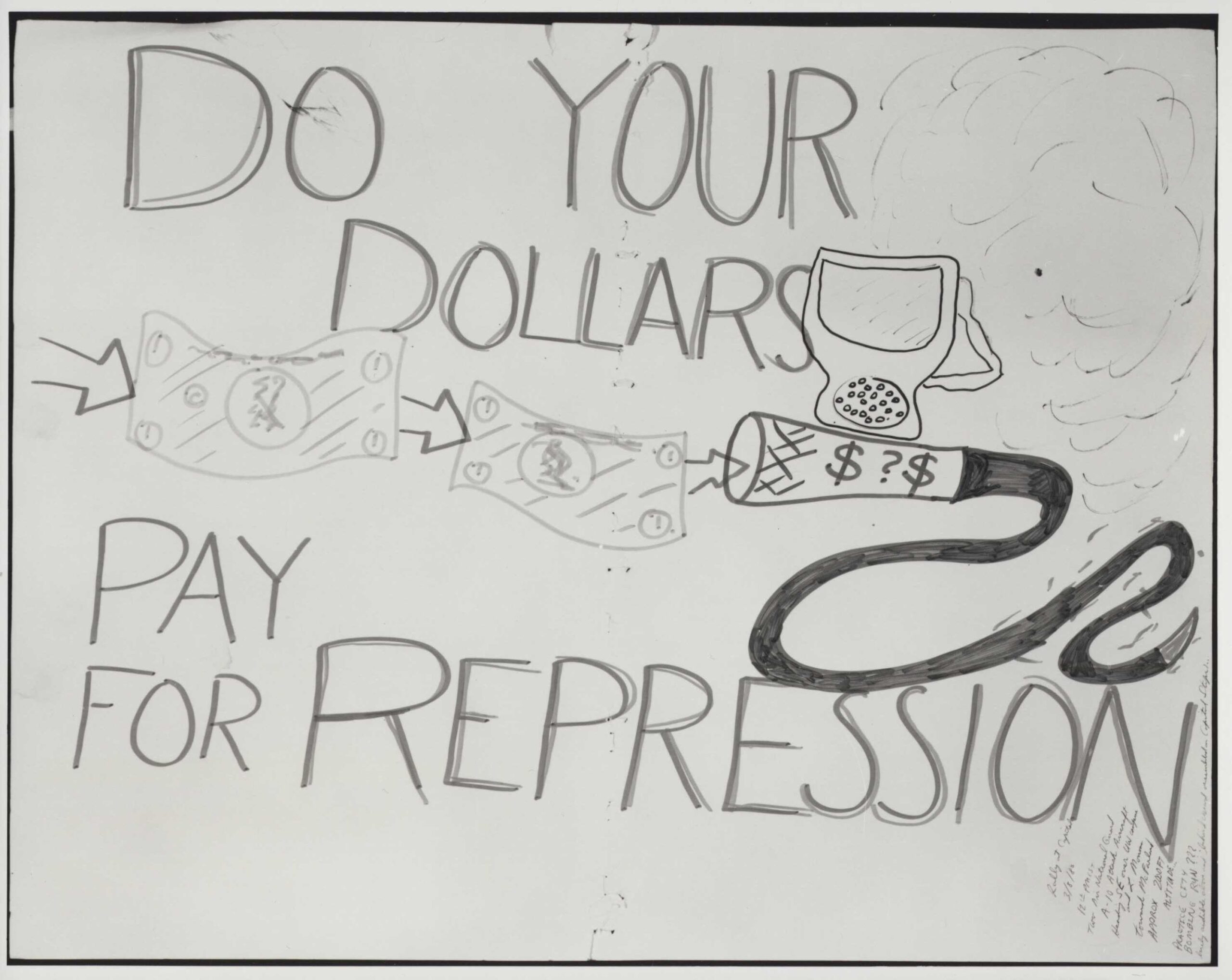

‘Do your dollars pay for repression?’

The activists’ demands for divestment were meant as a strategy to localize the struggle for college students, UW-Madison sociology Professor Gay Seidman told “Wisconsin Today.”

Seidman studied at Harvard as an undergraduate in the 1970s, where she became president of the Harvard Crimson school newspaper and drove coverage of the anti-apartheid South Africa movement. She came to UW-Madison to teach in 1996.

“There was a growing sense that nothing was working and saying, ‘The governments in the West were refusing to impose sanctions on South Africa,’” she said.

“There was a sense of, ‘We need to make people aware of South Africa,’” Seidman continued. “And, particularly for campuses, looking at the university’s investments in companies that did business in South Africa was a way to raise an awareness of, ‘It’s far away. Your life is not directly affected by it. But you were involved.’”

Students across the country have recently called for universities to divest from Israel and Israel-aligned companies. Students had a similar rallying cry decades ago for their schools to divest from apartheid South Africa’s government and companies associated with it.

But UW-Madison, thanks in part to its proximity to the state capitol, was “the first university that actually moved the needle,” Seidman said.

It took MACSA years to develop ties with city, county and state leaders, but eventually they got some traction.

In June 1976, following the Soweto Uprising, the Madison Common Council passed a symbolic resolution sympathizing with South Africans and condemning apartheid. A subsequent resolution — the first of its kind nationally — required the city to only award contracts to companies with no affiliation with South Africa.

MACSA then influenced the Dane County Board of Supervisors to pass a similar divesting resolution. Then came the entire University of Wisconsin system.

MACSA students were able to gain support for their cause from state Attorney General Bronson La Follette. He determined UW’s investments in companies supporting apartheid South Africa were illegal, according to a Wisconsin statute that prohibited “the purchase of stocks in firms practicing racial discrimination.”

So in 1978, the UW Board of Regents passed a divesting resolution that involved selling more than $11 million in stocks in offending companies.

“Everyone was completely surprised, because nobody would have thought that Wisconsin would have been the first place,” Seidman said. “But it was amazing. I attribute it to the people who were here — students who figured out that this was an option.”

Wisconsin educator finds parallels between conflicts in South Africa and Gaza

Prexy Nesbitt is a Madison-based educator, activist and scholar on Africa, foreign policy and racism. In the early 1970s, he worked for the American Committee on Africa, and visited UW-Madison’s campus as a guest speaker of MACSA, while making speeches about Southern Africa around the country.

Nesbitt told “Wisconsin Today” he would remind students protesting now of the deep roots and connections between the struggles of Palestinians and South Africans.

South Africa made headlines when it brought charges of genocide against Israel at the International Court of Justice in 2023.

“That comes out of the long history of relationship between the African National Congress and the Palestinian movement,” Nesbitt said. “But the roots of that are as a liberation movement and a liberation struggle. And my experience in South Africa has been that the mobilization by South Africans in South Africa against Zionism and against the right wing and the fascist support of brutality and racism has been very much a part of what today is also happening.”

Nesbitt also noted there was a “profound relationship” between the struggle in South Africa and the struggle for civil rights in the U.S. He said South Africans who came and studied at UW-Madison immediately got involved in that movement, too.