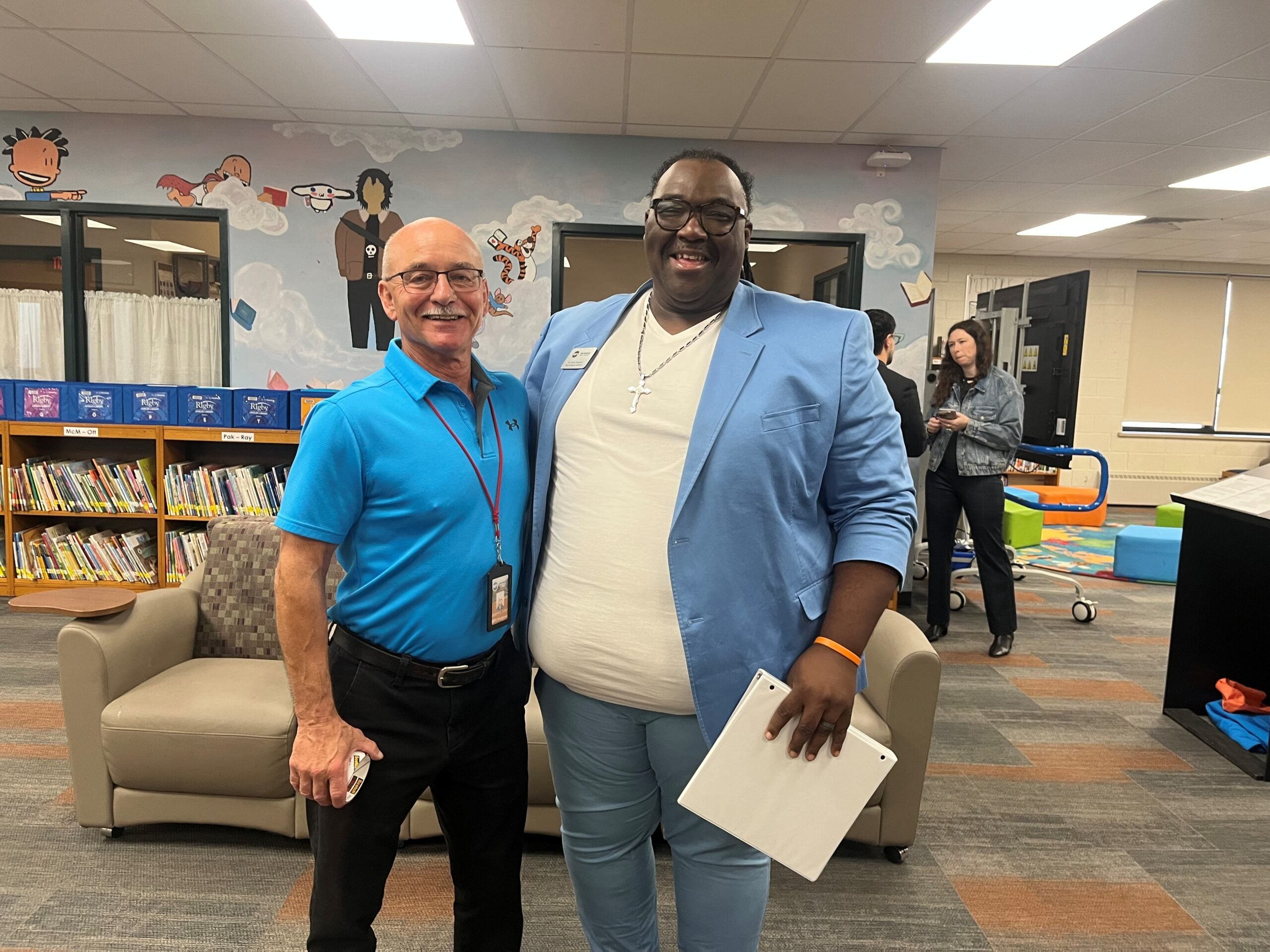

At a converted warehouse in Bronzeville last month, more than 75 Milwaukee leaders put their ideological differences aside to discuss an issue plaguing the city.

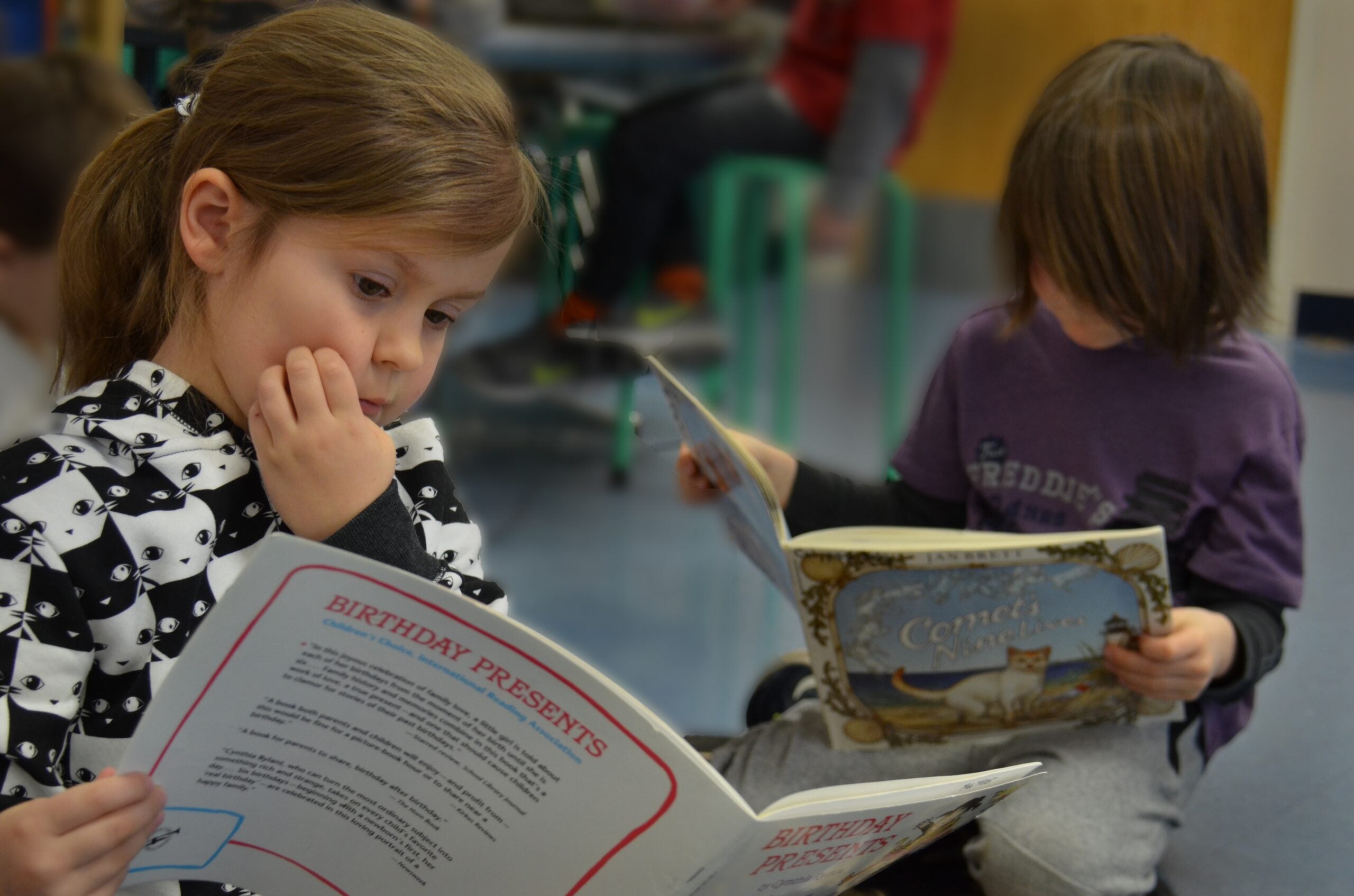

There are 31,000 children in kindergarten through third grade attending both private and public schools in Milwaukee. But only about 3,000 of those kids are meeting targets in reading, according to data compiled by long-time education activist Howard Fuller.

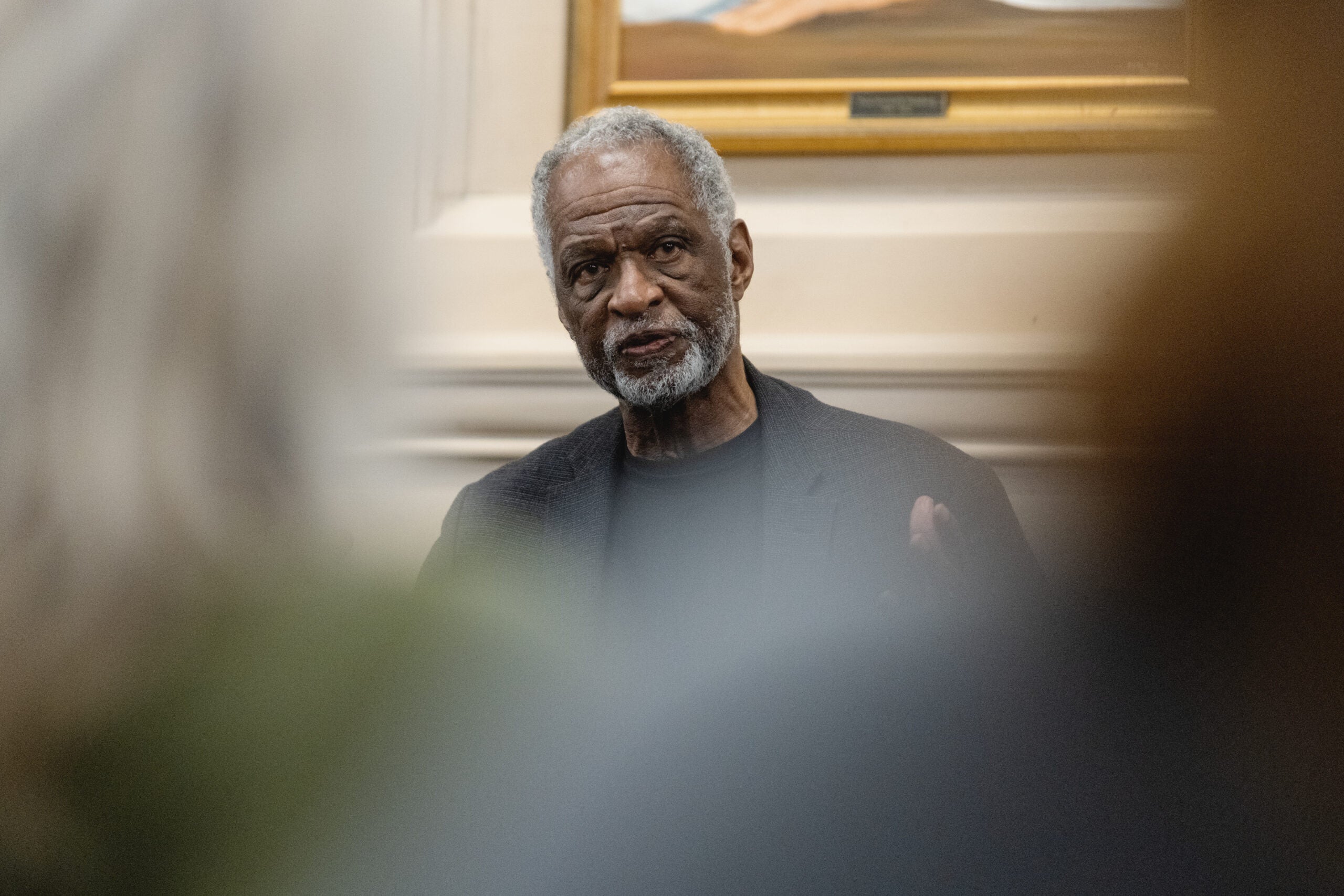

Reading scores for children living in Milwaukee have been the lowest in Wisconsin for years. But Fuller says that shouldn’t be accepted.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

A new Milwaukee Reading Coalition would focus on training teachers, which Fuller says is the first step in changing the overall problem.

“People will tell you all the things that could go wrong,” he said. “What about the parents? What about teacher resistance? What about bad teachers? But I say, if we can spend the next two years training 800 to 900 teachers, how many kids could be better off?”

But the coalition needs bipartisan support — and money, which Fuller and Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson hope will be allocated in the next state budget.

Milwaukee leaders have reached out to Gov. Tony Evers’ office and state legislators, but a bill has not yet been drafted.

“I’m certainly hoping that there will be some resources to help out on this, because it’s too important for us not to address it,” Johnson said. “We’ve seen for some time in Milwaukee that there is really a crisis as it relates to our kids having the requisite reading skills. We want to make sure that young people in Milwaukee, regardless of what school setting they happen to be in, are best prepared for success.”

‘No matter what type of school our kids are in … we want them to know how to read’

Johnson and Fuller pulled a group together on May 6. It included current MPS Superintendent Brenda Cassellius, dozens of civic leaders and prominent members of the private and charter school community.

Fuller said it was the first time in 30 years educators weren’t arguing about parent choice.

“We don’t have to agree on that,” he said. “But we can all agree that no matter what type of school our kids are in, no matter how they got there, we want them to know how to read.”

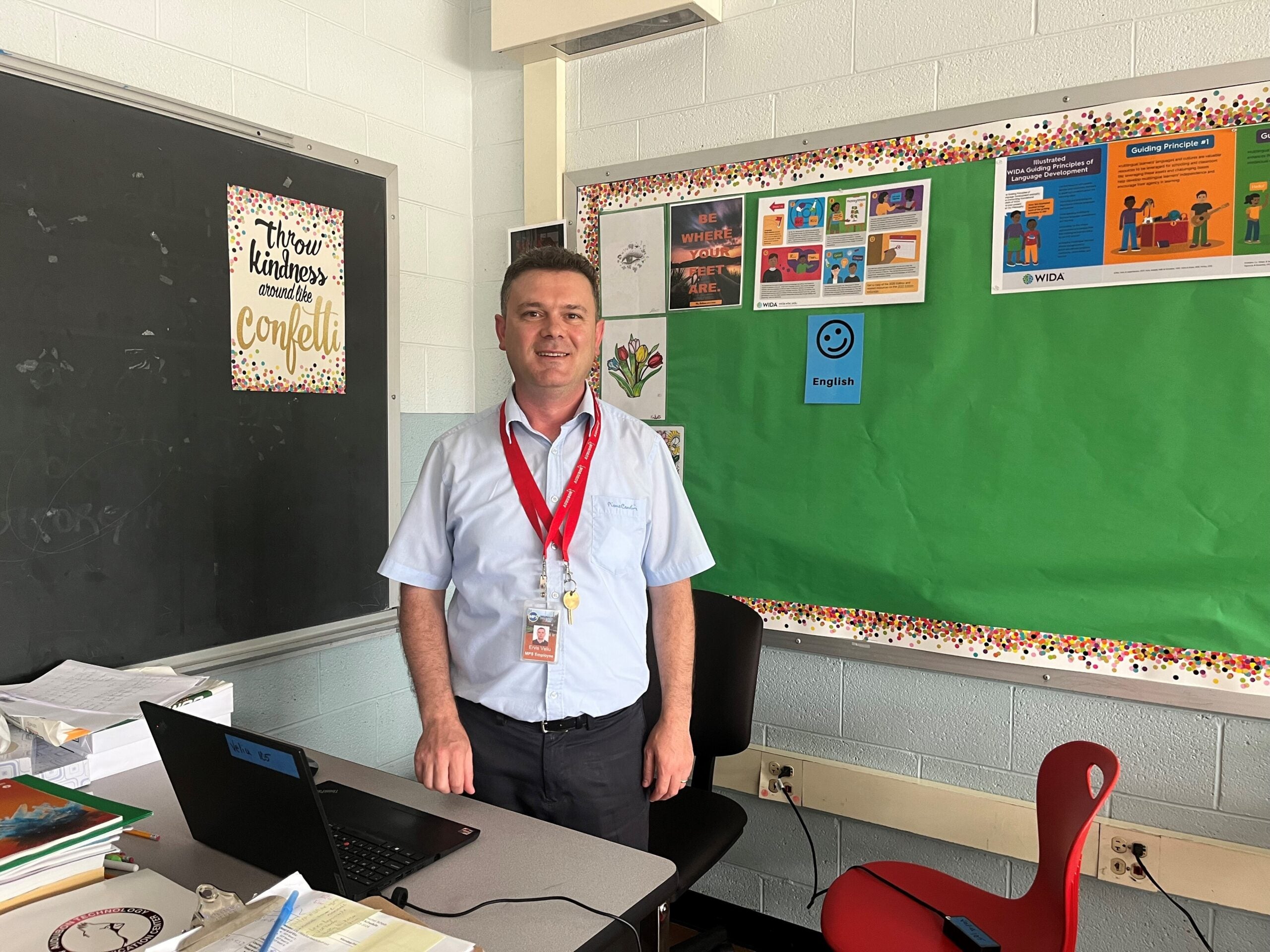

Nationally, there has been a push to teach what is known as the “science of reading,” a phonics-based approach that has been proven to work.

In 2023, a bipartisan law was passed known as Act 20, requiring schools to teach the science of reading.

Act 20 mandates changes to early literacy education in public schools for students in pre-kindergarten through third grade. It requires schools to use approved curriculum, provides professional development to teachers in science of reading and tests students on their ability.

Fuller says in Milwaukee, where most kids can’t read and most of the teachers have never been trained to teach reading, they have to start with the basics.

“The way that Act 20 is set up, it’s not going to do anything in the city of Milwaukee,” Fuller said.

The Milwaukee Reading Coalition would likely use LETRS, an acronym for Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, a teacher training program that has been dominating Science of Reading efforts, including in Mississippi, which many states look to replicate for its early childhood reading gains.

The program is long, intensive and expensive. It can take upwards of 160 hours to complete over the course of two years, which could be an issue with the Milwaukee teacher’s union.

That’s why Fuller says creating a separate entity, like the Milwaukee Reading Coalition, is essential.

If there is money attached to the program, it should not be given to MPS, said Fuller, a former MPS superintendent.

“You can go to your people and say, ‘We can’t get this money unless we do 60 hours of training,’” Fuller said. “Then put the union in the position of saying they don’t want money to help teach kids how to learn to read.”

Act 20 allocated $50 million to purchase curriculum and train teachers, but it has been tied up in court. The money will go back into the state’s general fund if the case isn’t settled by next month.

Fuller would like to see a portion of the money intended for Act 20 earmarked in the next state budget set aside for the Milwaukee Reading Coalition.

He doesn’t know how much money exactly, but says if Milwaukee has 11 percent of the children in the state, then about 11 percent of the Act 20 money seems reasonable.

MPS Superintendent Cassellius says she is on board and thankful for the efforts.

“I think it’s a great opportunity for the city to come together and wrap their hands around putting children first, particularly their literacy, and rallying support in order to be able to work together across all of Milwaukee for the betterment of our children,” Cassellius said.

In her proposed 2025-26 budget, Cassellius has made early childhood and sixth grade literacy a priority for the coming school year.

Fuller knows the Milwaukee Reading Coalition is a long shot. But the lifelong educator, now in his 80s, says he’s not going to stop trying.

“I mean, when I started this out, I thought we maybe had like a 20 percent change, now maybe a 45 percent chance,” Fuller said. “But I don’t know any other way to actually try to do something.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.