The legacy of America’s support for forcing Native American children into boarding schools for a century has left lasting scars in Wisconsin to this day.

The author of a new book, “Medicine River: A Story of Survival and the Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools,” shares how the trauma of the schools can be carried down through generations. These schools saw neglect and abuse all across the country and in Wisconsin.

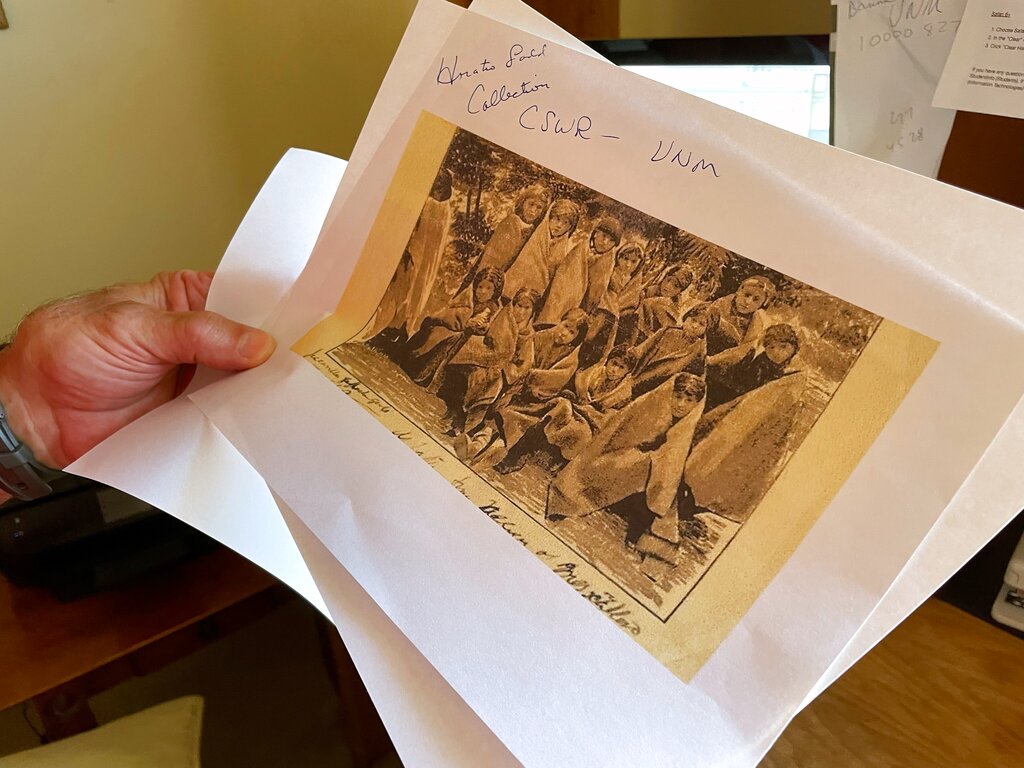

Mary Annette Pember is a national correspondent for ICT News. She’s a citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. In her latest book, she shares the story of her mother, Bernice Rabideaux, who in 1930 attended St. Mary’s Catholic Indian Boarding School in Ashland County. Rabideaux was just 5 years old at the time and wouldn’t see her mother again for two years.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We may in many ways represent one of the most incredible survival stories, both culturally and physically, of mankind,” Pember said recently on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

“Native people have survived. We’re incredibly scrappy people, and we have been able to make do with what we had and even flourish,” she said. “Some of these words fail to really paint an adequate picture of how we have gone on and how we have ultimately thrived. I think we can serve as an inspiration for a lot of people.”

Nearly 1,000 Indigenous children died at American boarding schools throughout their use, according to an investigation released last year by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

On “Wisconsin Today,” Pember talked about the generational trauma of boarding schools, her own family’s experience with the schools and the potential future of federal work on boarding school history.

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: Your mother, Bernice, was just 5 years old when she was sent to St. Mary’s. Was this normal for children to be taken from their parents and forced to go to these schools so young?

Mary Annette Pember: In some cases, yes. But by the time my mother went in the 1930s, they had, generally speaking, realized that sending children so young was not necessarily a great idea. My mother and her siblings, however, were in a situation where both their parents were no longer able to raise them and that contributed to their being sent to the boarding school.

KAK: Can you put into words what this separation was like for these children early on?

MAP: They really didn’t know what was going on. They were just kids playing together, and then one day someone came and took them away to this alien environment. My mother would often tell me that nobody ever explained anything to her, which was just really hard for a kid. Children typically blame themselves for things. And I’m sure she must have blamed herself. I can imagine she really suffered terribly.

KAK: You write how she threw her stories down before you like a gauntlet, a challenge. What was that like for you?

MAP: That whole sort of gauntlet aspect came later when I was a child. When I was really little, these were like my bedtime stories, and she put rather a positive spin on them. She was kind of the little girl who survived and was strong and defiant and prevailed. But later in life, she would communicate to me her disgust with the hypocrisy. Even though in many ways she reinvented herself as a church lady, it always stuck in her craw. She was very ambivalent about it.

KAK: She learned how to talk to white people at boarding school. She learned how to read people and how to read these nuns, and she was then able to take that away and apply that to the white people who lived in her communities. What was that like?

MAP: That may be among the most valuable lessons that Native children learned in boarding school, was how to navigate that world. What were white people threatened by? What made things easier for the children? They were able to figure out that culture that they had entered into.

And they used that moving forward to live in the white world, which it was and still is a white folks’ world. And if you can’t walk that walk and talk that talk, I think often you find you’re not as successful as you could be.

KAK: Since at least 2020, Congress has been considering the Indian Boarding School Policy Act, which would establish this investigative commission into our country’s boarding school past. Where does this work and especially the idea of reparations stand now?

MAP: I have to say that I really don’t think reparations will happen here. That’s just my personal opinion. They happened in Canada, and that work began in 2007. And the act did pass the Senate during the last administration, and the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs is taking it back up again. However, given the current climate, one wonders even if it is passed, I don’t know if it would be vetoed.

President Trump just recently clawed back from the National Endowment for the Humanities groups several grants — for instance, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and some other tribal groups to conduct interviews and collect stories and various projects. It was like $1.5 million, but there were a lot of organizations that were going to benefit from that. I think the wording from the head of the agency was that the project no longer aligned with their current philosophies.