On February 1, 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia broke apart upon reentering Earth’s atmosphere, killing all seven astronauts aboard.

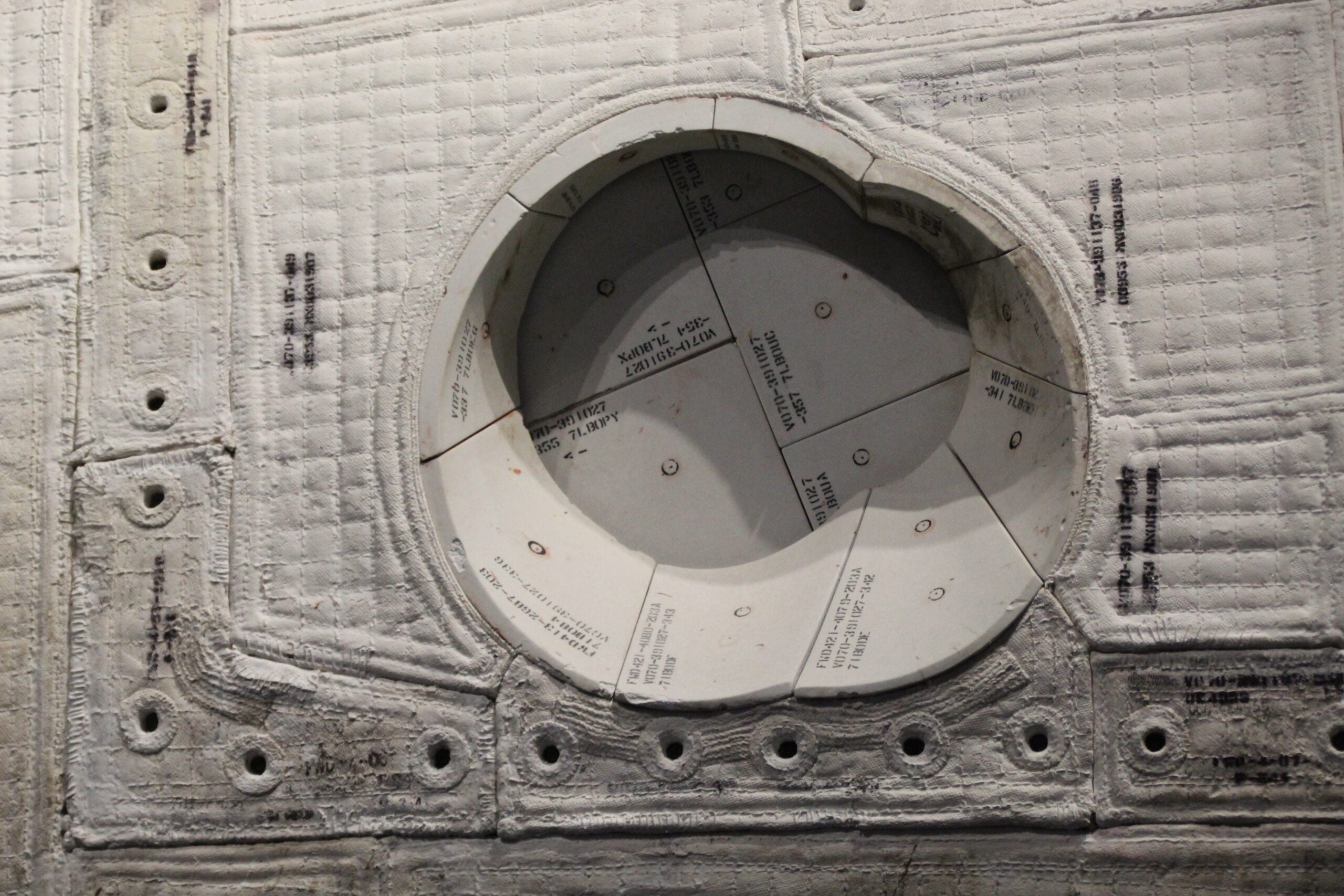

An investigation determined that a piece of foam broke off the external tank and struck a reinforced panel on the orbiter’s left wing, allowing hot atmospheric gases to penetrate the heat shield and resulting in the disintegration of the shuttle.

After a two-year suspension of the space shuttle program, work on the thermal protection systems, or TPS, for subsequent shuttles resumed.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

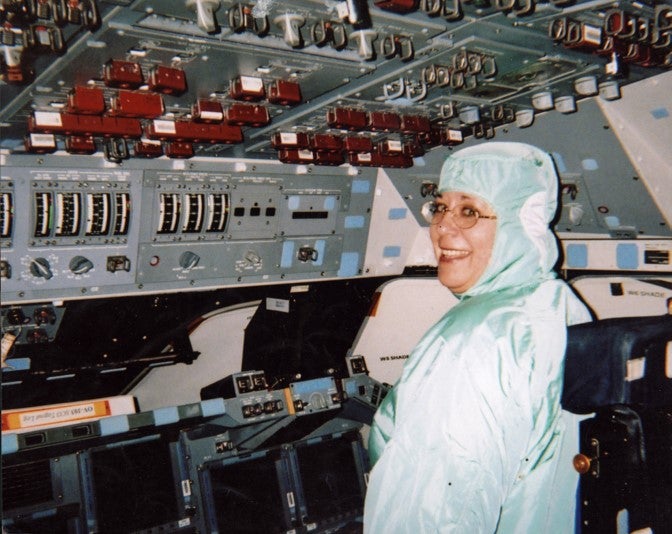

That’s when, in late January 2005, Jean Wright joined NASA’s “Sew Sisters” — a team of 18 female aerospace composite technicians who sewed the extreme heat-resistant fabric (an alternative material to hard, TPS tiles) covering the exterior of the space shuttles, and giving them their iconic white appearance.

“Those are fibrous or flexible, insulated blankets — initially called a ‘frizzy,’” Wright said, pronouncing the acronym FRSI, which stands for Felt Reusable Surface Insulation.

On WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show,” she explained that a FRSI consists of “quartz fabric, a quartz thread, spun quartz batting and fiberglass backing. Depending on the heat load the blanket was going to get, we made them roughly the thickness of a placemat to two inches thick. And believe it or not, they could do the same thermal protection as tiles did. The blankets (could withstand up to) 1,300 degrees, and it saved a ton of weight by switching to the blankets.”

Wright credits her hiring by NASA to her ability to grasp the importance of the task, her sewing skills and passion for the U.S. space program.

She would go on to work on the shuttles Discovery, Endeavor and Atlantis, which completed missions for the International Space Station, before the space shuttle program ended in 2011.

Wright is the focus of the 2023 children’s book by Elise Matich “Sew Sister: The Untold story of Jean Wright and NASA’s Seamstresses.”

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Larry Meiller: Not many people can say they were a seamstress for NASA.

Jean Wright: That’s true. But it’s a little frustrating when people find out that I was a seamstress for NASA and say, “Oh, you sewed the spacesuits.” No, we actually built flight hardware for the space shuttle.

LM: How did you get interested in sewing and then the space program?

JW: I’ve been sewing since I was 7 in Flint, Michigan. And like most people around my age, back in 1969 when we first walked on the moon, I was just captivated. And even though Michigan was so far away from (the Kennedy Space Center in) Florida, I just knew somehow I was going to end up there. That was something I always wanted to do.

LM: How do you make fabric that can withstand that kind of heat the space shuttles endure?

JW: Well, if you’ve ever seen cotton candy being made, they take sugar and they melt it to a liquid. We take finely ground quartz and melt it to a liquid. You lift that thread up, and when the air hits it, it makes a thread. Then they twist it around and weave it into a fabric. But it’s actually quartz stone that we make the fabric out of.

LM: It’s amazing to me that you were not only using sewing machines, you were hand stitching.

JW: I would say at least 40% of the flight hardware we built was literally with a needle and thread.

If we had film that was too thin to put through a sewing machine, we would pre punch holes with an awl. Or if we were working with a special thread — because we had a special high-temperature, coarse thread that melted at 3,200 degrees. It couldn’t go through a sewing machine. So we had to sew that one by hand. And that would be primarily for thermal barriers on the nose area and landing door (of the shuttle where it got the hottest). We also had over 5,500 silver polyimide blankets we made out of a special silver film, and that was the barrier from radiation for the astronauts. Those would be underneath the payload bay doors.

The most unique hand sewing we did on the shuttle, I would have to say, was on the blankets that go around the engines. They’re eight and a half feet across, and they’re for sound suppression around the engines. They’re called dome heat shield blankets. And Lurch would be the one that would quilt the 125 rows that radiate from the center out. But we would hand sew the sleeving on the edges. We used Inconel wire thread to hand sew the blankets around the shuttle engines.

LM: I’m wondering about tolerances. I mean your work had to be really exacting.

JW: There’s a tendency for some people to go, “Oh, it’s just women who sew.” Our stitches were 10 to 12 stitches per inch, and quality control would be there with their scale ruler making sure we were on spec. We really had tight tolerances, because everything had to fit perfectly.

LM: You’re actually a docent now.

JW: I am a volunteer docent at the Atlantis exhibit (at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex). We are fortunate to have the space shuttle Atlantis there. Someone like me with thermal protection experience, or somebody who’s worked on the engines, can answer guests’ questions. And when we have a big launch, we escort guests. It’s a wonderful job. You keep your little toe in there. And we still get to see astronauts all the time.

LM: You are the focus of the 2023 children’s book by Elise Matich “Sew Sister: The Untold Story of Jean Wright and NASA’s Seamstresses.”

JW: I met Elise at the Atlantis exhibit back in 2019. She wanted to start a series of books on women, kind of like the book “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Who Helped Win the Space Race.” So over the course of a few years, even through COVID-19, we wrote each other back and forth. She’s a beautiful writer and illustrator. The book came out on October 3 — the day that Atlantis launched into space. I thought that was a good omen.

LM: You have garnered a lot of attention. How does that feel?

JW: It’s not so much about me. I just want people to know NASA is looking for creative people who know how to write, draw, and people like me who sew. NASA is looking for everybody. I want to be a good ambassador to let kids know that, yeah, there’s a chance. If you have a dream and a unique specialty, NASA probably will need you.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.