One of the most common myths about dementia — a general impairment in thinking and memory — is that it’s a normal part of aging.

But Dr. Nathaniel Chin, an assistant professor and geriatrician at UW Health, wants to bust that myth.

“There are plenty of people who live a really long and healthy life that never develop advanced thinking changes,” said Chin, the director of medical services with the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and host of the “Dementia Matters” podcast.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In a recent appearance on WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show,” Chin explained that thinking does change in people as they age. But these “age-related thinking changes” are not synonymous with dementia, nor is dementia something that’s inevitable.

“That’s why we are so focused on trying to treat it and then ultimately prevent it,” he said, noting between 30 and 40 percent of dementia cases are preventable.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Larry Meiller: There’s a lot we do not know about the cause of dementia, but what are the primary risk factors for memory loss later in life?

NC: Well, first, the most common brain diseases that cause dementia are going to be Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, a cousin of it called Lewy body disease, and then frontotemporal disease. But those are all accumulations of proteins in the brain or blood vessel narrowing.

And then when we think of other factors below the head that can affect our thinking, that’s going to be things like our mood, sleep apnea, physical inactivity, thyroid conditions, vitamin deficiencies.

So there’s a whole bunch of things that we can address that can actually affect our thinking ability.

LM: Alzheimer’s is probably the most commonly understood or known cause of dementia. What changes are happening in the brain when you develop Alzheimer’s?

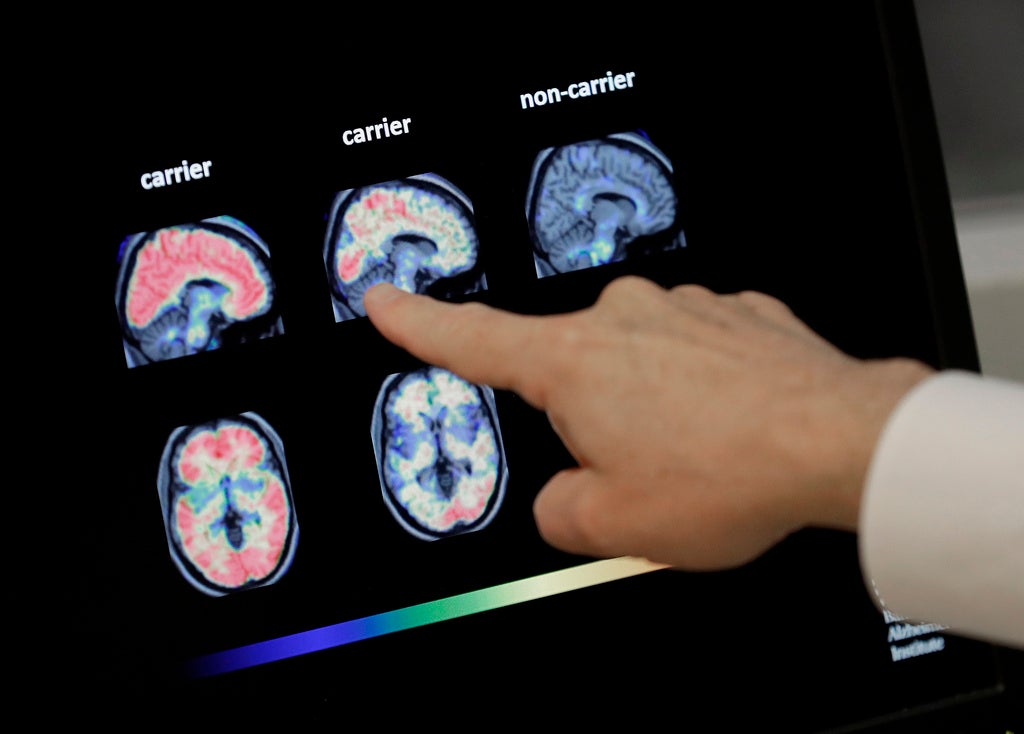

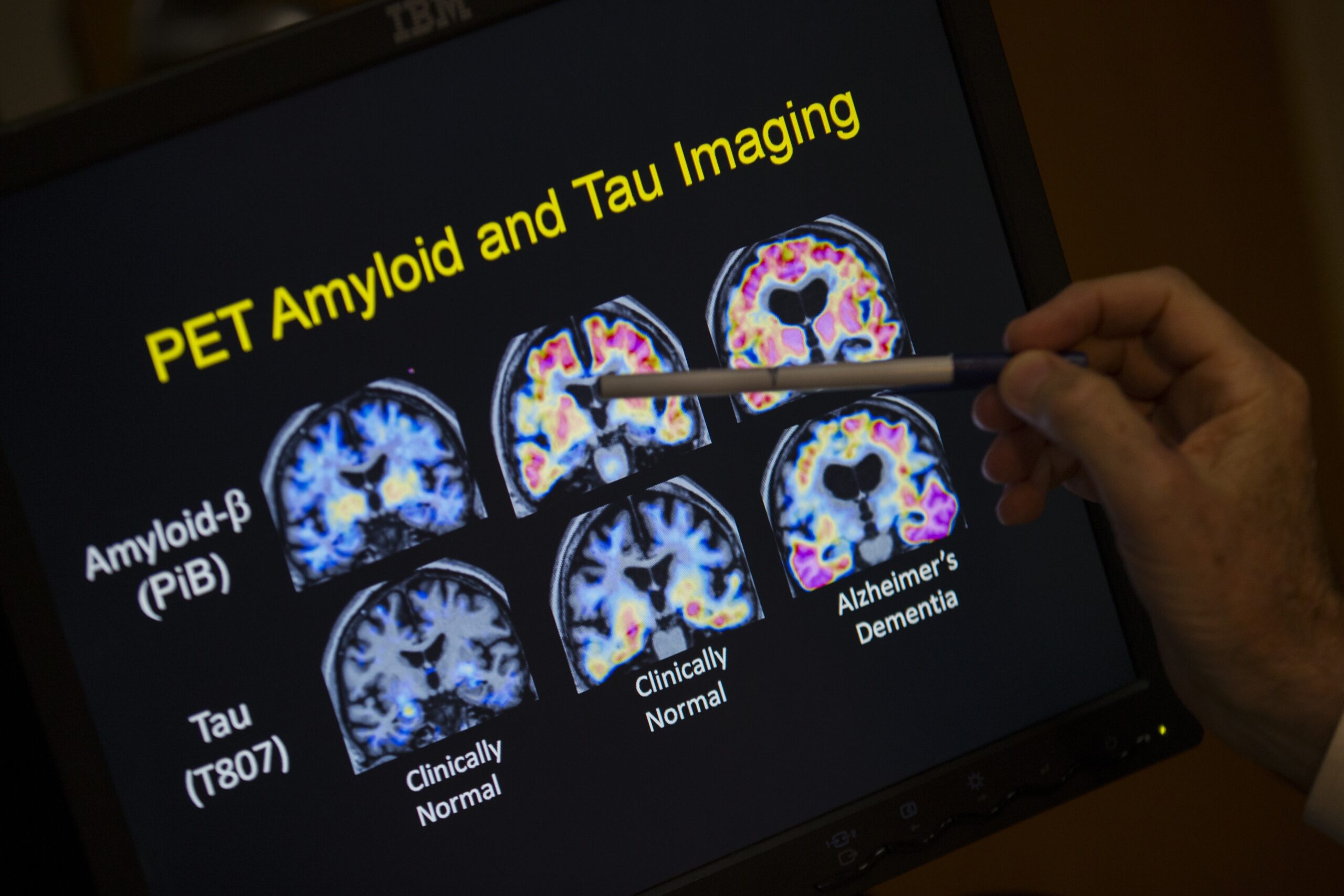

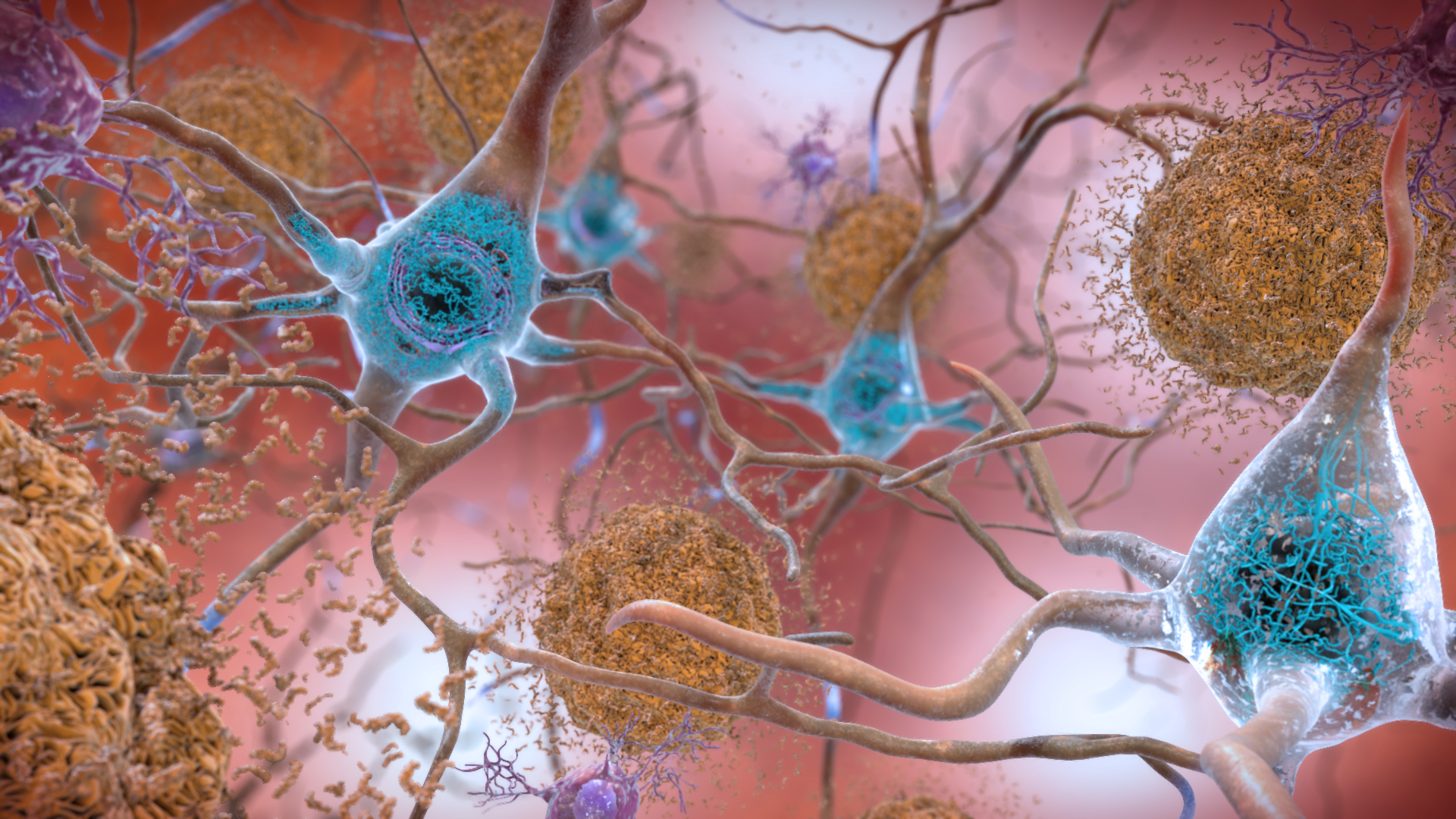

NC: In Alzheimer’s disease, there is this accumulation of two proteins that we are not able to get rid of. The first one is called amyloid and that develops first. The second one, which develops years later, is called the tau protein. And those two proteins lead to dysfunction in the connections among brain cells and then eventually lead to brain cell death.

And when you don’t have as many brain cells, you don’t have the communication, and therefore you start having symptoms.

And so we really learn this timeline, or this progression, of Alzheimer’s because of our research participants, and in particular in Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention, which includes 1,800 fantastic Wisconsin people who are followed every other year for over 20 years. We’re really learning a lot because of their dedication.

LM: What actions can you take to reduce the risk of dementia? And is there anything relating to reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease for yourself?

NC: I’ll answer the second question by saying we’re really looking into that: What can we do that impacts this amyloid protein or the tau protein?

But when it comes to dementia itself, I think of four main things about how can we address or look at prevention:

- Treating depression, thyroid and vitamin deficiencies. This is the reason why people really should go and talk to their primary care provider and get evaluated, because they’re very common. And they can be they can be treated.

- Managing Vascular risk factors and blood vessel health. That’s things like diabetes or your blood sugar, high blood pressure, if you’re smoking, obesity, weight in general and physical inactivity. Those are all been linked to having a having a higher risk of of dementia. And they’re all very treatable.

- Taking pro-health measures. There are other things that I like to think about that are more pro-health or pro-wellbeing. And that’s exercising eating well, being social, keeping your brain stimulated.

- Protecting your brain. We really have to protect our brain. So that includes wearing a helmet, wearing a seatbelt and preventing head injuries.

And then, more recently, the connection between dementia and hearing loss and making sure that we’re identifying and treating hearing loss.

LM: Let’s say there’s somebody out there listening who’s 60 years old and says, ‘You know what? I don’t do exercises. I don’t eat right. Probably too late for me anyway.’ Or is it?

NC: Absolutely not. It’s never too late. A good place to start is today.

And I would actually say when people tell me, ‘Oh, I don’t exercise, I don’t eat well,’ all I say is, ‘Well, great. We have this huge room for improvement.’

I just want you to walk then, if you’re not ready to go for a swim or go on the elliptical machine. Please give me five minutes of walking. Or if you can’t walk —and there are plenty of people who have those disabilities — then let’s do some chair exercises.

So there’s always a way.

LM: There was a study funded by the National Institute of Aging that found a link between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and lower cognitive test scores. Can you tell us about how our environment is related to our brain and memory health?

NC: Yeah, this was a very interesting study, and it was actually using a tool that was designed and created by one of our own, geriatrician Dr. Amy Kind. It’s called the Neighborhood Atlas, which is free for anyone.

It’s really looking at environmental and social factors in your neighborhood.

And what it found was that regardless of race, if you live in a more disadvantaged neighborhood, you perform worse on thinking tests. And they accounted for education, for some genetics, other health factors.

So it really speaks to the fact that when it comes to our thinking ability, there are other external factors at play that we can address. And a lot of this is policy-driven, but a lot of it is under our own control, whether it’s the foods that we eat or how active we are.

But studies like this one — using the Neighborhood Atlas is really allowing for not only scientists, but I would say the public policymakers to see that there are other things we can do outside of a clinic that can make a meaningful benefit to the community.

LM: What role does mental health and emotional wellbeing play in terms of risk of dementia later in life?

NC: Depression is one of the main risk factors, one of the most powerful risk factors for dementia later in life.

What’s tricky about this is that mood changes could actually be one of the first changes of an actual disease in the brain. And so there’s a lot of research looking at that. So, they’re intertwined, which to me just says it’s incredibly important that we address our mental wellbeing as well as our physical wellbeing. And likely the outcome of doing that is going to be not only feeling better, but then protecting our brain.

LM: I’m thinking too about chronic stress, anxiety. This has got to affect risks for dementia.

NC: You’re preaching to the choir here, Larry.

Now, stress in general is not a bad thing. It’s what prompts us to get things done. Evolutionarily, it’s what prompted us to run away from that attack.

But when it’s chronic and daily from the lives that we’re living — you’re having too much cortisol in your body, you’re having too much of this sympathetic nervous system drive — that is leading to negative outcomes.

Blood vessel health, brain sizes becoming a little bit smaller, obesity, high blood pressure. So there are lots of negative effects from the way our society just lives in general when we have chronic stress that we don’t address.

Caller: I read somewhere that if you don’t get enough sleep, there’s plaque that builds up in your brain. And if you get a deep sleep, then there’s enzymes that wash away the plaque that causes dementia. Is that a true?

NC: Sleep is incredibly important. So that is very true. People who don’t sleep well don’t perform as well on thinking tasks. They have higher weights, higher blood pressure, lower moods. And so sleep is really important just for your overall wellbeing.

But in addition to that, when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, specifically, we have seen that the amyloid plaques, that first protein, gets cleared normally during the deep phase of your sleep. So stage three sleep. People who never get into stage three or deep sleep or they don’t do it enough, there is this belief that then the the protein isn’t being cleared out at the way it should. So then it can can sort of build up and stay in the brain.

We do see this as a risk factor to Alzheimer’s disease or at least the biology of Alzheimer’s. But really, we’re still looking into it directly to see if there’s a way for us to use this, to treat, prevent or address Alzheimer’s disease.