Thousands of people travel to rural Northern Wisconsin for the annual American Birkebeiner ski marathon. And to Eau Claire-based author Jerome Poling, the electric feeling of crossing the finish line brings athletes across the globe back year after year.

“When you’ve done it once, you just want to come back and keep doing it as long as you possibly can,” Poling said on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

In his fifth book, “American Birkebeiner: The Nation’s Greatest Ski Marathon,” Poling writes about his 40 years of experience both covering the race as a journalist and participating as an athlete.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I saw my first Birkebeiner in 1982 and then started doing full Birkies in the early 1990s,” Poling said. “I’ve done 25 full races.”

Set in northern Wisconsin, the Birkebeiner put the city of Hayward and town of Cable on the map for cross-country skiers around the country and around the world.

In the interview Poling shared more about his passion for the race and what it was like interviewing some of its pioneers.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: In your book, you take us back to the early days. Set the stage with the founder, Tony Wise.

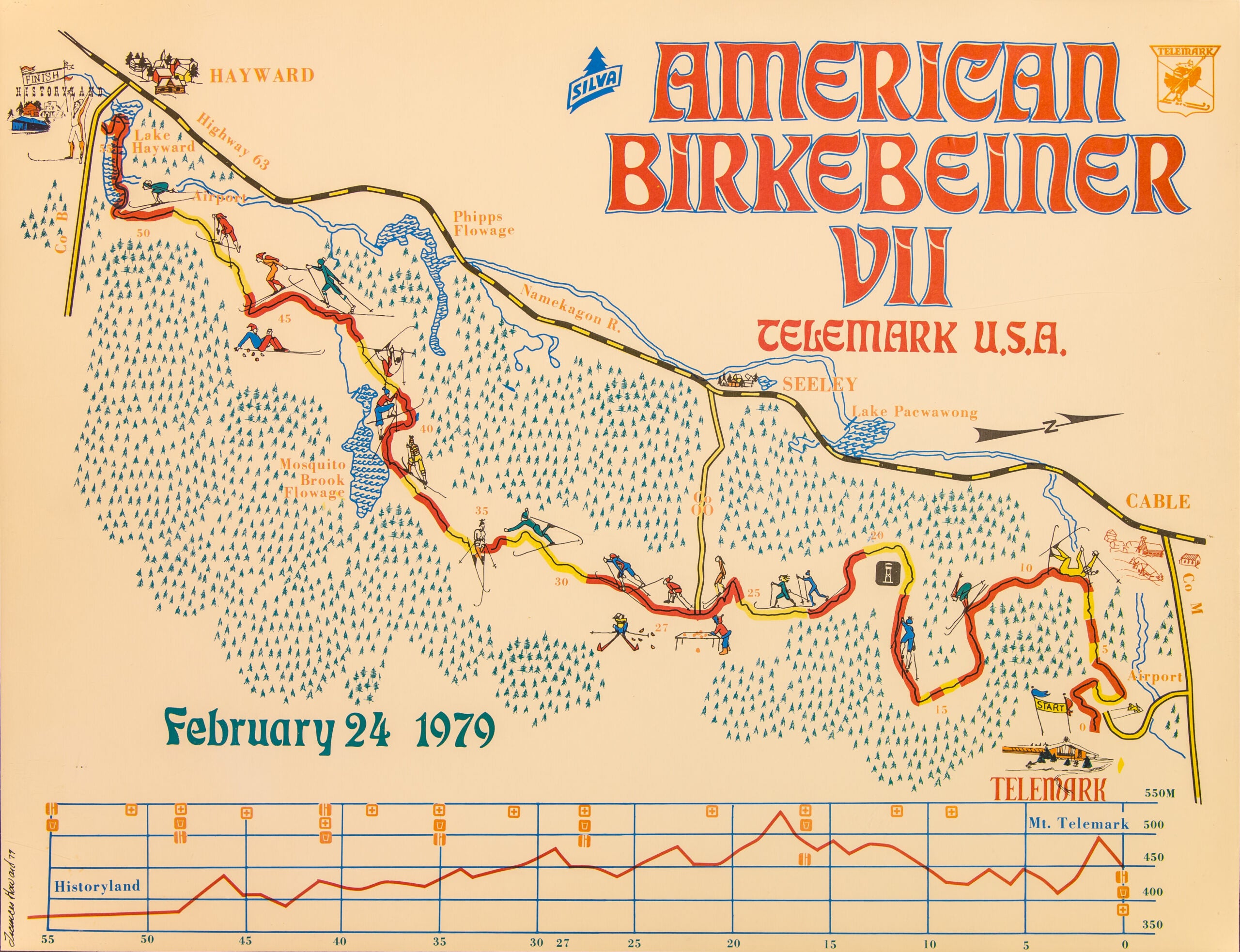

Jerome Poling: Tony Wise was a Hayward native. Around the mid-late 1960s, cross-country skiing started to gain momentum in the United States. At the very same time, he was opening the — now gone, but famous — Telemark Lodge up in Cable. He was looking into the idea of adding cross-country ski trails at Telemark and various people indicated to him that to get more attention for the ski trails at his lodge, he should start a race. And that’s exactly what he did.

But of course, Tony, being the big thinker that he was, he didn’t just start a race. He started the American Birkebeiner, which at that time was a real outlier in the ski world. I don’t believe there were any other 50-kilometer cross-country ski marathons in the United States. So when he started the race in 1973, it’s not surprising that only 35 skiers signed up for the long race, and only 54 signed up for the short race. It was a very small beginning for what’s become a very big event.

RF: You do a great job of setting the scene for that first year when nobody knew exactly what was happening. How many people did you interview to write about that very first Birkie?

JP: I did more than 60 personal interviews for the book itself, but some of my favorite ones were the people who were part of that first race in some fashion. One of them was Bob Treeland, the director of the race. He worked at Telemark Lodge for Tony Wise. He was in charge of figuring out how to get from Hayward to Cable without any designated ski trail.

Today, we know the Birkebeiner as this famous trail, essentially designated for skiing. But for the first four races, they had a sort of jury-rigged trail on logging roads, fire lanes, railroad ditches and various strung-together sections of road that they had to use to get from Hayward to Cable.

I also interviewed the person who groomed the trail the very first year. He pulled two people on Alpine skis behind him all the way from Hayward to Cable to set track. So today we have these giant six-figure groomers that put down beautiful groomed tracks. But back then, that was the trail for the first Birkie — two people pressing in snow on Alpine skis being pulled behind a snowmobile.

RF: Tony Wise cited his inspiration Curly Lambeau — as in Lambeau Field — helping found the Green Bay Packers and putting a smaller community right on the national and global map. How much has the Birkebeiner meant to that local community — Hayward, Cable and the surrounding region?

JP: It’s had a tremendous impact on that area. Tony left to (go to) Harvard and got his master’s degree, but he wanted to come back to Hayward and put his hometown on the map. He did. Just from the Birkie perspective, it became this international event with skiers from around the world coming to Hayward for the race. So right now, I think about a million dollars is spent by the Birkie foundation just each Birkie week, and that doesn’t even count all the money that is brought in to the hotels, the restaurants, the gas stations, everything, because of all of the thousands of people who show up for that race. So the economic impact has been incredible.

RF: In the book you also shine a spotlight on volunteers. These days more than 2,000 volunteers are involved in making the annual event happen. How does that community come together to do all this work? What did you see behind the scenes?

JP: I talked to a lot of volunteers who are just as dedicated as the skiers themselves to be part of this event. They love seeing the excitement. They love being at the food stations and helping out the skiers. They put hundreds of hours in getting their crew ready. It’s an incredible effort for Hayward and Cable … that really only have about 3,000 people. And then you realize that more than 10,000 skiers are in these races and about 20,000 or more spectators. So it’s just an incredible celebration of a Nordic sport in the middle of winter in northern Wisconsin, that just turns the whole whole area into a festival of skiing and good feelings and good times.