As many as 11 ancient canoes have been found lurking at the bottom of Madison’s Lake Mendota, according to archaeologists with the Wisconsin Historical Society.

In 2021, a dive team excavated a dugout vessel, believed to be 1,200 years old, from Madison’s largest lake.

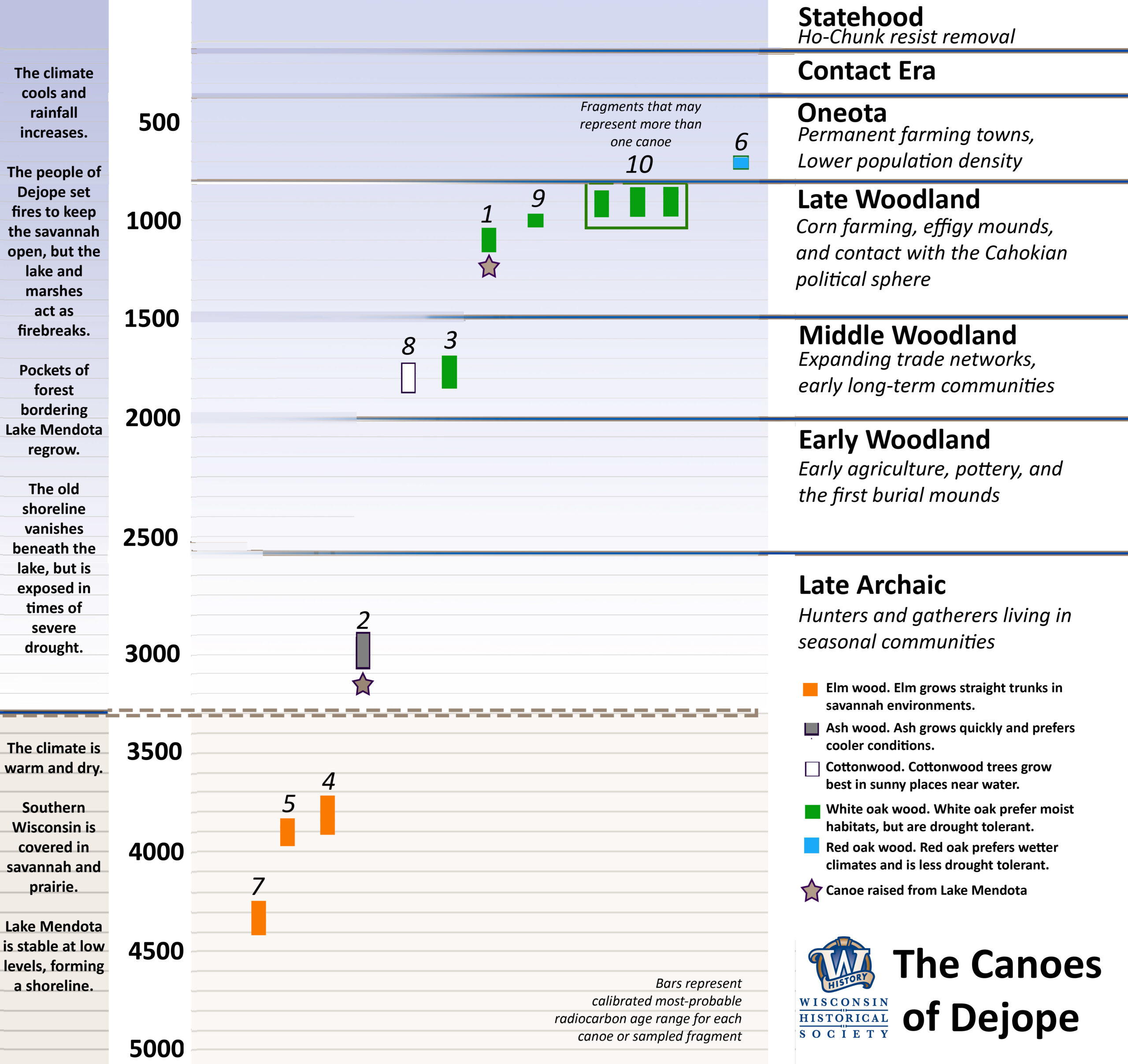

Nearly a year later, onlookers cheered while divers painstakingly pulled a second wooden boat from the inland lake. At an estimated 3,000 years old, that dugout canoe was the oldest of its kind ever discovered in the Great Lakes region.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But now that record has been shattered after maritime archaeologists discovered pieces of even older canoes in the same area of Lake Mendota.

The oldest is made from elm and dates back to 2,500 B.C.E., making it roughly 4,500 years old.

In total, archaeologists have found at least 10 spectacularly old canoes buried in a section of the lake, including the two canoes excavated in 2021 and 2022, the Historical Society announced Thursday.

The cluster could include pieces from as many 11 separate canoes, pending further analysis of wood fragments.

Researchers believe canoes were once stored for winter

The ancient boats were found submerged, along about 800 feet of what archaeologists believe was once an ancient shoreline.

The canoes are further evidence of an archaic civilization that flourished between 3,500 and 4,500 years ago, in what’s now known as Wisconsin’s Four Lakes Region, State Archaeologist Amy Rosebrough said.

“Archaeologists hypothesize that the canoes may have been intentionally cached in the water to prevent freezing and warping in the winter months and were later buried by natural forces over time,” says a news release from the Historical Society.

It’s possible that, over centuries, people kept returning to the same spot for canoe storage, Rosebrough said.

But it’s also possible that modern-day Wisconsinites are only glimpsing one section of the lake bed that’s become partially unearthed.

One theory: That section of Mendota became exposed over time because of the wakes from boats turning around in a nearby marina, Rosebrough said.

“What’s eating away at me, honestly, is: Are there more?” Rosebrough said, noting that nearby lakes like Monona and Wingra could hold similar treasures. “Is there a bathtub ring of canoes all the way around Lake Mendota? And that’s just one lake.”

The canoes were discovered in ancestral territory of the Ho-Chunk Nation, and researchers believe they were built by ancestors of modern-day Indigenous nations, Rosebrough said.

At the same time, the canoe builders lived “so far back in time that we were we would be at a complete loss of what they called themselves,” Rosebrough said. “The canoes are telling the story of the people who have been here for a very long time, regardless of what they call themselves.”

The Ho-Chunk Nation refers to the Four Lakes Region as Dejope and to Lake Mendota as Tee Waksikhominak.

“Seeing these canoes with one’s own eyes is a powerful experience, and they serve as a physical representation of what we know from extensive oral traditions that Native scholars have passed down over generations,” Bill Quackenbush, historic preservation officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation, said in a statement. “We are excited to learn all we can from this site using the technology and tools available to us, and to continue to share the enduring stories and ingenuity of our ancestors.”

Quackenbush is an expert in the use of ground penetrating radar, a non-invasive technique that’s been used by indigenous nations to uncover ancestral burial sites.

Additional studies planned while all but 2 canoes remain submerged

The Historical Society partnered with Quackenbush and with Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Larry Plucinski to conduct ground penetrating radar, or GPR, studies of the frozen lake in 2022 and 2023.

Quackenbush is continuing to analyze that data, and additional GPR expeditions are planned later this year.

Work is underway to preserve the 1,200- and 3,000-year-old canoes, which were previously excavated from the lake. Those two canoes will eventually be displayed at the Historical Society’s Wisconsin History Center, set to open in 2027 at Capitol Square in downtown Madison.

But the rest of the canoes in the cache, including several dating back more than three and a half millennia, will likely remain covered in depths of Lake Mendota.

The Historical Society believes the ancient boats are too fragile to move, after being exposed for years and years to natural elements, as well as to human disturbances, including pollution and boating wakes.

“The decision was made in collaboration with Tribal Historic Preservation Officers after archaeologists determined that the additional canoes are not physically intact enough to withstand recovery by divers and then the process necessary to preserve the canoes,” the Historical Society said.

In the meantime, researchers will try to learn as much as they can from the boats that remain submerged. Later this year, the Historical Society plans to work with the Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist and the University of Iowa to use a sonar boat to further map the lake.

It’s a crime to destroy, remove or deface archeological sites, the Historical Society warns, and researchers are urging divers not to disturb the area.

“We’re going to have to really rely on the diving community,” Rosebrough said. “For the most part, our divers are very responsible people. So we’re going to rely on them to do the right thing.”

Canoes in cluster range from 800 to 4,500 years old

Tamara Thomsen, a maritime archeologist who first spotted the two canoes that were excavated in 2021 and 2022, took slivers from the rest of the boats in the cache. Those pieces were used for radiocarbon dating and other types of analysis.

The youngest boat in the cluster is about 800 years old. That red oak vessel dates back to the Oneota period, when indigenous people built permanent farming towns.

Archeologists previously believed the 3,000-year-old canoe was carved out of a single piece of white oak.

But analyzing wood cells that have been waterlogged over centuries is tricky, and researchers have since concluded that the canoe excavated in 2022 was carved from an ash tree.

“Once you get a little further back in time, the wood isn’t really wood anymore,” Rosebrough said. “It’s fairly mushy. When you touch it, it feels kind of like a bagel that’s been left out in the rain. All that’s holding the rest of the wood up is the water inside.”

Along with ash, white oak and elm, people made other canoes in the cluster using cottonwood and red oak.

The varied construction materials offer clues into how the climate of Wisconsin’s Four Lakes region has shifted over time. They also offers clues about the people who built the boats.

Hard woods like elm, ash, cottonwood and white oak are challenging for wood workers, a testament to the craftsmanship of early canoe makers, in the Woodland and Late Archaic periods, Rosebrough explained.

“People (were) going for the wood that is local, even if that wood is very, very difficult to work with and that says something about the skill of how the canoes are made,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.