For Bob Dylan, his famous lyric of “She’s an artist/She don’t look back” might as well as be a professional mission statement. For the last 20-plus years, however, his management team has taken a different approach, releasing albums of hidden gems from Dylan’s back pages that offer fans plenty of reasons to ignore old Bob’s advice.

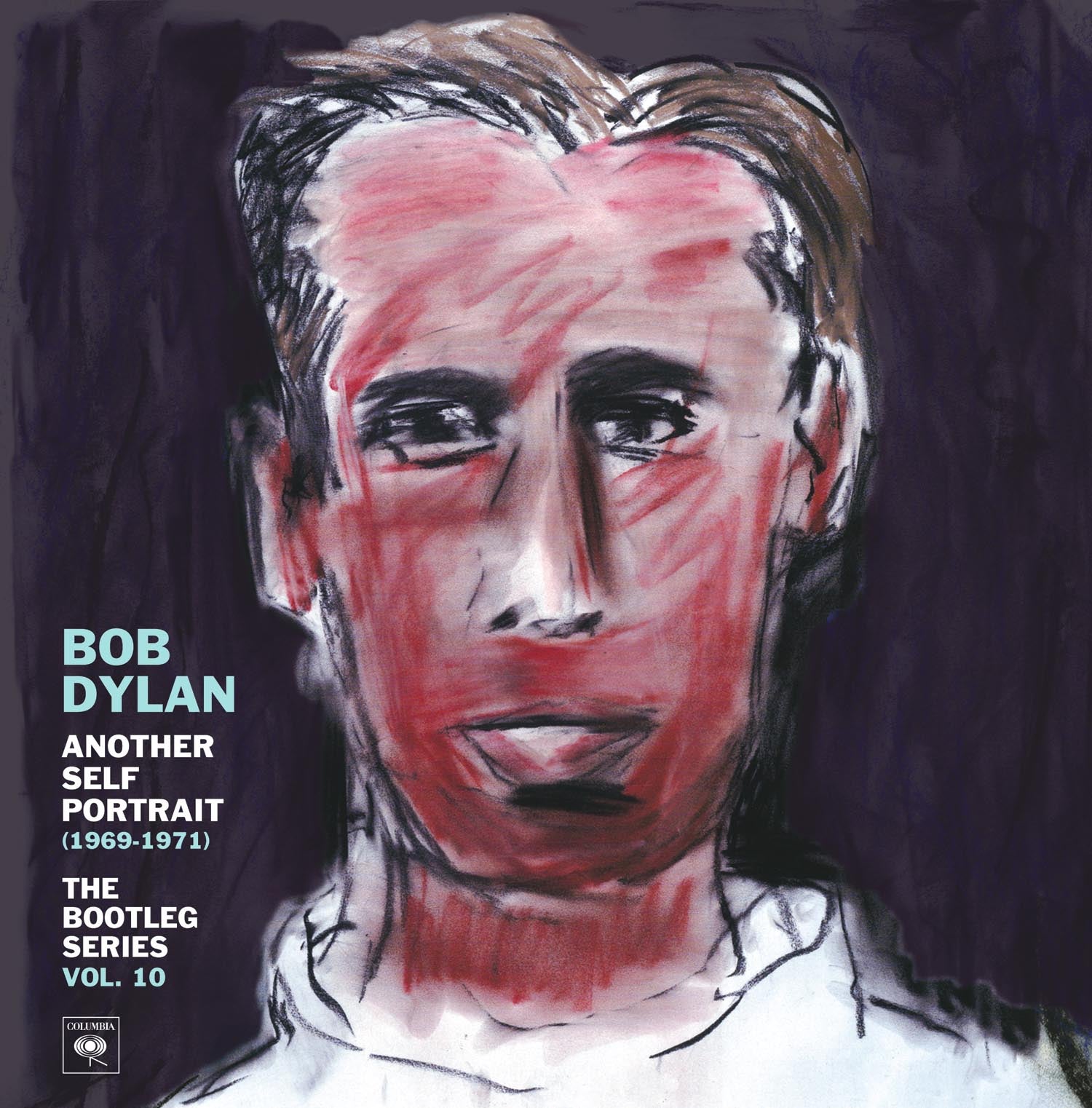

The latest installment of this archival series, titled “The Bootleg Series Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969-71),” seeks to reverse opinions on one of the most reviled periods in Dylan’s creative life. Unfortunately, in their push to revise the popular perception of these years, Dylan’s assistants obscure the true treasures of this period.

Since the release of the first installment of “The Bootleg Series” in 1991, Dylan Inc. has conducted a carefully timed campaign to mine the back catalog. Making a buck will always be a motivating factor for releasing new product and yet, there remains ample evidence that Dylan’s backers aspire to the higher purpose of second guessing history. They believe that reviewed with the passage of time, Dylan’s unreleased wares offer countless examples of why history needs to be revised again and again when it comes to the Bard’s creative output. That even the scraps on Bob’s cutting room floor underscore his genius, deserve critical kudos and warrant greater mass adulation.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

These years targeted in “Another Self-Portrait” were the height of Dylan’s so-called country-music phase and cover a period that yielded albums like “Nashville Skyline,” “Self-Portrait,” and “New Morning.” This new release posits a theory that rather than a colossal failure — best exemplified by critic Greil Marcus’ infamous Rolling Stone review of “Self-Portrait” — the very late ’60s wasn’t a Dylan devoid of a muse. It was actually another incident of the master being far ahead of his adoring public.

Ultimately, Team Bob misses the mark here. The discs emphasize covers and bland material that is mildly entertaining and perhaps enlightening about an artist in search of new purposes. There’s a parade of lukewarm collaborations with Beatle George Harrison, keyboardist Al Kooper, guitarist David Bromberg and a gaggle of Nashville session men with whom Dylan recorded since the mid-’60s. But no matter the sales pitch, it remains perfectly clear why most of these lost tracks were outtakes.

Oddly, at the same time, Dylan’s minions undervalue a key concert performance — included in this package as just a bonus disc for completists– that makes an excellent case for rediscovery and reconsideration by Dylanologists and casual fans alike.

The box set comes in two forms: The standard version includes two discs of outtakes, alternate versions and other odds and ends from a five-year period in Dylan’s canon (despite the set’s title claiming it runs from 1969 to 1971) and then a four-disc compilation that boasts two additional records — a remastered version of the original “Self-Portrait” album and the complete live recording of Dylan’s performance at the 1969 Isle of Wight Festival, backed with the Band. It is the Isle of Wight concert that commands new attention.

At that time, the Isle of Wight appearance was something of a curveball thrown to Dylan’s ravenous public. These years were his times of retreat as he struggled to reconcile and redefine his relationships between his personal life, his ambitions and fans. He’d shed previous public personas as a protest-music troubadour and motor-mouth surrealistic hipster and settled into a life of low-key domesticity in Woodstock , N.Y. , with his wife and young family. He woodsheded a new, roots-ier sound with members of the Band and released ever more enigmatic albums. Above all though, he firmly kept his audience at a distance. He even shirked an opportunity to perform at the famous festival that was literally at his doorstop to make his first major performance in years in England at the Isle of Wight.

In the subsequent decades, Dylan’s loose and rollicking performance at the festival was mostly written off as anticlimactic. After so many years in near seclusion and with three-fourths of the Beatles and Eric Clapton looking on, many in the crowd were waiting for an appearance of what they hoped would be a rock ‘n’ roll Messiah. Dylan couldn’t and wouldn’t deliver on that kind of overhype. Afterwards, a couple of poorly mixed cuts were abstracted on “Self-Portrait,” including Dylan fubbing a line on “Like A Rolling Stone,” and a tin-y, scratchy-sounding bootleg offered a pinhole-sized glimpse of Dylan the country crooner and his soul brothers in the Band.

Remixed and now ripe for reevaluation, the Isle of Wight performance demonstrates a full vision of both the Americana music that Dylan and the members of the Band conceived during “The Basement Tapes” era two years before as well as the relaxed, easy chemistry that existed between Dylan and his most famous sidemen. This music would serve as a template for the Eagles, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the Grateful Dead and others. It has left a legacy in both rock and country music that continues to reverberate today.

The Isle of Wight gig was a shock. First, Dylan’s reverb-rich vocal style is diametrically opposed to the jagged, hoarse voice of his early years. He really tries to sing as if he were a balladeer. The Band, then at the pinnacle of its powers, is energetic and their attack — song-by-song — is wonderfully flexible, but they’re all fairly casual about the delivery. (At times, during “Lay Lady Lay,” “Like A Rolling Stone” and “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35,” listeners can hear Dylan coaching the group on the next song’s melody.) These guys sound gloriously ragged, as if they and Bob could have been playing in the basement again just as much in front of hundreds of thousands of people.

The songs, reinterpreted to fit a country-leaning consciousness, can be nicely divided into moods interspersed throughout the set — scorching roadhouse rockers, moody cowboy ballads and a quartet of folk material that Dylan performed alone. Songs like “She Belongs To Me,” “Maggie’s Farm” and “Highway 61 Revisited” are reborn as brawny, almost bawdy Hank Williams songs. No longer easily categorize-able as folk or blues or mountain music, the versions here are funky grooves. Drummer Levon Helm drives the rhythm like a locomotive as Rick Danko’s basslines tense and flex to shove the melody forward. Pianist Richard Manuel and organist Garth Hudson appear to have a near-telepathic connection, at one turn trading embellishing licks after a break and then switching deftly to watch the other’s back. Guitarist Robbie Robertson is in full guitar hero mode. His leads lacerate the song, stinging, trilling and then jerking the melody in between each verse.

Most impressive was how Dylan reclaimed “The Mighty Quinn (Quinn The Eskimo),” which had been a hit in the United Kingdom thanks to the group Manfred Mann, and recast it has a saloon sing-along augmented by the Band’s patented country funk. The instrumentalists keep the melody brilliantly oft-kilter and the rhythm pulsing until Helm, Danko and Manuel join Dylan like a chorus of hound dogs. And Robertson’s white-hot solo, despite a blast of accidental feedback, is the perfect example of his unique, pinched approach to expending guitar notes. U2’s the Edge is one of those who should “be jotting down notes.”

Without the Band, Dylan’s four solo performances early in the set also establish that he remained an effective spokesman for his songs even if he now preferred to have musicians giving form and shape to his music. “It Ain’t Me Babe” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” are quick and breezy renditions that harken back to his Village days. In comparison, Dylan is more intense on “To Ramona.” The song’s Spanish waltz rhythm comes from Dylan’s vocal cadence and excellent acoustic guitar flourishes. Even better was his take on the traditional Scottish folk song “Wild Mountain Thyme.” Haunting and romantic at the same time, Dylan’s arrangement serves both to highlight the crooning vocal affectations that he was then experimenting with and his skills as a guitar accompanist.

Whether with a band or not, this music is thrilling. But it is on the slower numbers that fans have the time and space to appreciate all that these guys put together. The typically sappy “I Threw It All Away” sounds downright majestic. On “Minstrel Boy,” Dylan joins with Helm, Danko and Manuel to sounding like a troupe of heartbroken barflies staggering out of a pub. For “Lay Lady Lay,” Helm proves his versatility as a percussionist coping the pattern that studio veteran Ken Buttrey put down on the original studio recording and expanding upon it to give the song a consistent energy. Robertson’s incandescent guitar lines tug at listeners’ ears and Hudson uses every trick in his arsenal to make his organ support the music’s twists and turns.

The keyboardists continue to shine on lesser-known songs like “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” and “I Pity The Poor Immigrant,” which are so entrancing that Dylanophiles should recalibrate their playlists. Manuel’s piano converts “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” from a folk song rewrite into an elegant gospel hymn. Hudson, meanwhile, earns his pay — plus some — just on “I Pity The Poor Immigrant.” He straps on his accordion and decorates the song to give it a wonderful southern European mood. Hudson partners will Robertson, whose guitar notes ring like church bells before he makes it trill like an Italian mandolin. The song is already mysterious and now is nearly cinematic in scope. Both songs now lend Dylan’s croon plenty of room to maneuver, whether his purpose is sermonizing or storytelling.

If you seek a performance that will kick the doors down, the Isle of Wight concert might not be for you. It doesn’t have urgency and the ferocity of Dylan and the Band’s explosive shows during their 1965-’66 tours. But, that’s not the point. Both the performers and their audience were in fundamentally different places. In the mid-’60s, the musicians were smashing together influences, defiantly discovering new forms. By the late ’60s, it was about rediscovery and reinterpretation of the past and working within well-established forms. This mindset would continue to shape Dylan’s artistic worldview for the rest of his career.

It’s unlikely that this fumble will stop the Dylan machine’s desire to release future versions of “The Bootleg Series.” (Rumors circle that “Blood On The Tracks,” “Blonde On Blonde” and “The Basement Tapes” are next in the docket.) But with “Another Self-Portrait,” those guardians of the Dylan legacy invite another kind of second guessing — this time of their own decision-making. We now know they might not be any better than their boss at choosing winners and losers.