“Look here, you bunch of basement noise,” Bob Dylan pronounces in one off-the-cuff lyric sung during a few late-1960s recordings that earned legend in rock-music circles as “The Basement Tapes.” But this jokey, admonishing dig likely summarizes Dylan’s own wrong-headed assessment of what has gone on to be some of the most sought-after and ultimately important tape reels in pop-music history.

Dylan’s dismissive feelings aside, “The Basement Tapes” are that rare kind of music that was unintentionally transformative on many levels — aesthetically, culturally and even economically. These recordings, which were initially only available on rock’s very first bootleg album, stand as a crucial pivot point for Anglo-American music. Their influence extends far beyond just what Dylan and the five musicians who constituted his once and future backing group, the Band, imagined they were up to during that fateful year nearly a half century ago in the Woodstock, N.Y. area. Alas, in a simple twist of fate, something was happening here, but now it’s Dylan and company who didn’t know what it is.

What it is was a casual musical exploration of American roots music (including folk, country, blues, R&B, gospel, mountain music, early rock ‘n’ roll and plenty of sub-variants from there) — just at the time that many in the West were drenched in psychedelia and consciously skewing the past for a brave new world. It was also probably Dylan’s most prolific writing period, yielding a killer lineup of his canon’s classics.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But for all “The Basement Tapes” accidentally achieved, the majority of these lo-fi recordings have remained largely out of reach for most listeners, the inaccessibility feeding their mystery. Fans only saw, read and heard about “The Basement Tapes,” listened to a cover song by the Byrds or Manfred Mann and they experienced the aftermath as this music seeped out into the culture — the kind of stylistic counter-revolution brought about just by listening. They witnessed the sonic and visual transformation in contemporaries like the Beatles, Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead. Or, as time passed, they saw the emergence of acts that had clearly learned from the open-minded example of “The Basement Tapes” or thrived in a music world that these recordings gave birth to. Everything from the mega-selling country-rock stylings of the Eagles to alt-country, neo-folk and contemporary country hybrids like Uncle Tupelo, Mumford & Sons, the Decembrists, Garth Brooks and Taylor Swift are traceable back to a batch of crude home recordings made by a pack of 20-somethings and whose purpose was ostensibly just “killing time.”

Because of Dylan’s ambivalence, the catalyst for all this change has been frustratingly unavailable. Some fans heard these recordings on bootlegs. Others heard a portion of the songs that was subsequently released on a critically praised but incomplete 1975 double album. A couple of tracks escaped purgatory for an afterlife on Dylan compilation records. Instead of these attempts satisfying demand, they only fed conspiracy theories and whetted demands for more. Poor-sounding bootlegs gleefully filled many of the gaps.

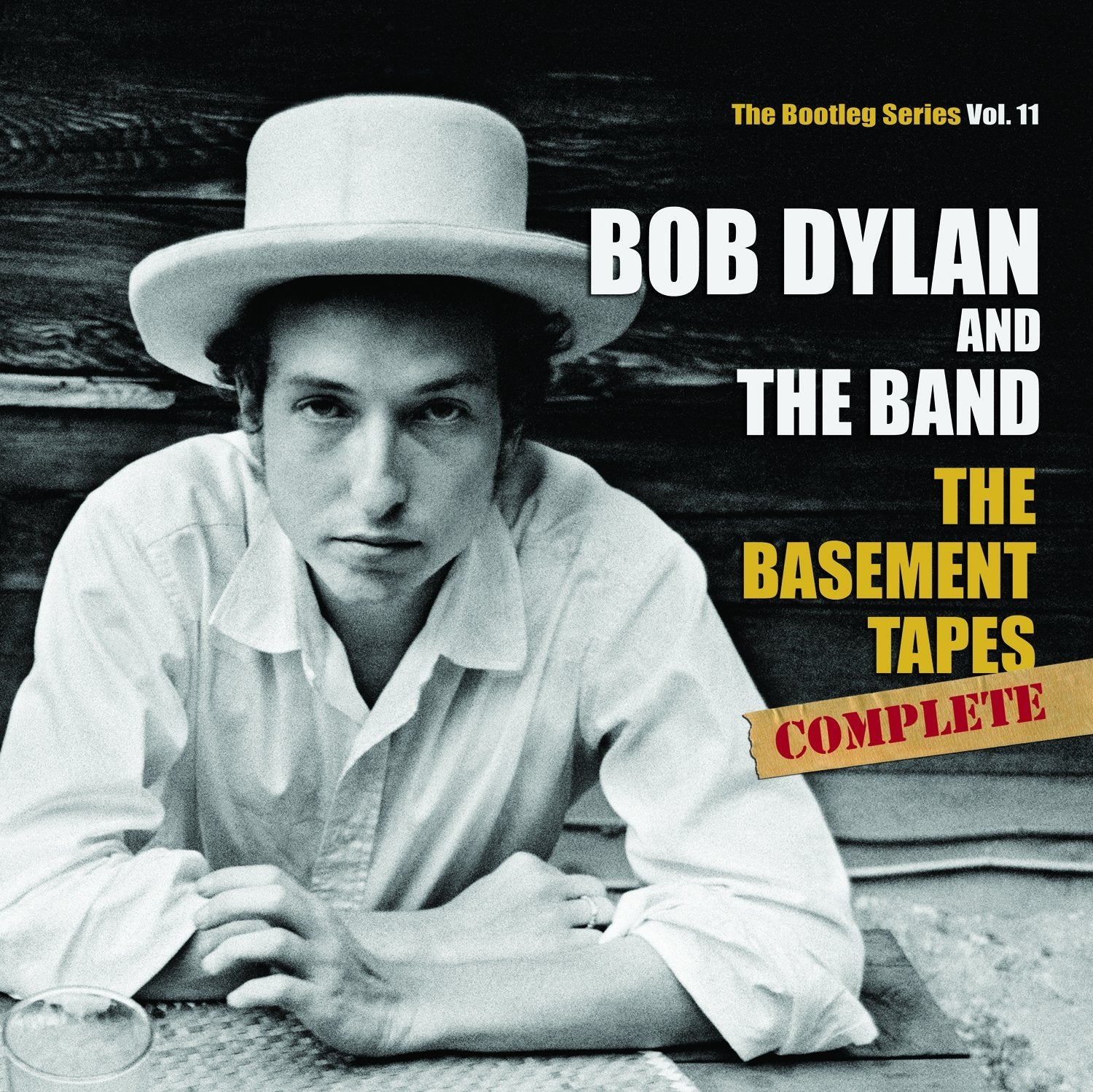

And so, after all this time, Dylan and his helpers have finally opened the vaults to release a comprehensive collection of what he and the Band recorded during those months of 1967 and early 1968. “The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11” is a six-CD set sporting 139 songs that asserts it includes nearly everything recorded during the dozens of informal songwriting workshops, song-swapping sessions and rehearsals that were held chiefly in a pink-painted split-level called Big Pink. (A two-disc “Raw” version of the box set is also available.)

Why now? The box set’s release was likely due to pure business synergy: two related projects were slated to hit the marketplace in November and going now was the surest way to achieve maximum splash. The first, “Lost On The River: The New Basement Tapes, Vol. 1,” is a “Mermaid Avenue”-like album spearheaded by producer T-Bone Burnett and featuring Elvis Costello and a slew of younger, roots-rock luminaries tag-teaming to add music to unused Dylan lyrics from the “Basement” period. A Showtime documentary, “Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued,” examining both the Big Pink antics as well as the “Lost On The River” recordings is coming later in the month.

No matter why they were finally released, that they exist at all is the important part. All the hype is right. Frequent comparisons between the “Basement” recordings and Harry Smith’s seminal “Anthology of American Folk Music,” which was so important to the ’50s and ’60s folk-music boom, are spot on. Reviewers like Robert Christgau and others famously noted when the 1975 double album came out that these songs could have been the best songs of 1975, 1967 and maybe 1867. They surely still rank among the best in 2014.

‘Basement Tapes’ Born During Period Of Recovery, Restoration

Going back in time, Dylan and the Band recorded these loosely arranged songs during a lengthy period of self-imposed seclusion. In the preceding two years to arriving at Big Pink, Dylan was both an artist on fire and one at the center of a firestorm. He had jettisoned his earnest, protest-singer image for a wilder, lyrically-abstract rock ‘n’ roll sound — provoking outrage among many fans and political ideologues. At the same time, Dylan was writing and recording some of his most revolutionary work. During those years of 1965 to 1966, Dylan released rock’s most definitive single, “Like A Rolling Stone,” and a holy trinity of great albums – “Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde On Blonde” – which typically rank as the singer’s creative and commercial zenith.

To support his new electrified musical vision, Dylan hired a formidable Canadian bar band formerly known as the Hawks. (The proto-Band’s name came from the fact they had originally been assembled by Arkansas rockabilly also-ran Ronnie Hawkins.) Dylan and the Hawks would eventually tour the U.S., Australia and Europe, where they nightly faced booing and other audience disruptions. The blur of tour dates, nightly abuse and the amphetamines they were likely dabbling in forged this combo into a bruising live unit. It forced the musicians to discover an exciting and explosive version of Dylan’s music — melding folk-music structure, Chicago blues, Southern R&B and country influences — under the harshest of battlefield conditions. (A previous Dylan box set, “The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The ‘Royal Albert Hall’ Concert,” captures one of these incredible performances and is easily one of the greatest concert albums of all time.)

With the European tour concluded, Dylan and the Hawks seemed locked to continue their frenetic pace with slate of creative projects (more recordings, a book, a concert/art film) and more U.S. tour dates already in the planning stages. All of this literally came to a stop when Dylan was injured in a mysterious motorcycle crash during a July 1966 tour break in Woodstock. (Such is the Dylan mythos that many speculate the crash was only a cover for a) the singer weaning himself off drugs and/or b) the demands of his station.)

Whatever the truth about the crash, Dylan’s very public retreat upstate offered a break in the action and became a definitive marker in his career. “Electric” Dylan, the wild-eyed, poetry-spewing moppet of those years, was gone forever. With all future demands put off indefinitely, it would be nearly two years before a new Dylan and the rechristened Band appeared in public again.

Off the road, hidden from public view and enveloped in a closed-mouthed aloofness that Dylan’s circle always exudes, this was a time of recuperation, restoration and reflection. The singer only began to rouse to his calling in the late winter of 1967 by quietly doing a little songwriting. His manager, Albert Grossman, likely prodded Dylan to pen some new material for other artists to cover, as well as to make use of these musicians who had been sidelined for months but were still on the payroll. Perhaps Al Aronowitz, a New York music journalist who was Dylan’s go-to toady at that time, explained it best how the Big Pink activities got started during an interview with this reporter: “They’re musicians. They just play,” he said.

The group for most of the backwoods recordings included guitarist Robbie Robertson, bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel and keyboardist Garth Hudson. The Band’s drummer-vocalist Levon Helm was a late-comer to “The Basement Tapes” sessions. Helm had left the group in 1965 during the American leg of the tour because of the booing and, according to Robertson, doubts about the pairing with Dylan. He was eventually lured back to the group in October or November 1967 as the Band readied to record their debut album.

The sessions — first at Dylan’s house, then Big Pink and possibly other nearby locales — saw the musicians grow a sound that was the antithesis of the roaring ferocity of the ’66 tour. The new sound was quieter, tightly focused and had a pronounced country tilt. Squirreled away in the Catskill Mountains, this was a rediscovery of Americana in popular music.

These recordings also offer a rare glimpse of Dylan’s creative process. Many of the early sessions feature the musicians playing a lot of cover songs (Johnny Cash, Hank Williams, the Carter Family, Curtis Mayfield, John Lee Hooker, among others). While some of the songs are reminiscent of their original arrangements, others are reworked and reimagined. Committing these covers to tape were likely attempts at setting a tone from which like material would emerge or an effort to see if changing the chords, alternating tempos or adding different rhythms would allow them to pull another song out of the source material. Dylan and the Band’s musicality is impressive. The terrain the players covered veered across the map to include sea shanties, cowboy songs, chain gang work songs, weeping country ballads, Appalachia mountain hollers, urban electric blues, Spanish music, reverent gospel, New Orleans funk and traditional folk music. Vocals, instruments and ideas were easily shared (as was probably the weed). Eventually, new Dylan originals began to emerge in the middle and latter part of the period.

The sometimes daily sessions also awakened something new in Dylan as an artist and songwriter. Whether inspired by the Band members — particularly Robertson’s — fondness for rock and roll, blues and gospel or just a desire on Dylan’s part to simplify his songwriting, the tunes that came forward were the antithesis of the elusive, surrealistic poetry of the “Blonde On Blonde” years. These were stripped-back story songs, rich with Biblical parables and commonplace symbolism.

Dylan also sounded bolder in his singing than he had been in the past. One can clearly hear Dylan demonstrate the influence of country crooners and folk-music balladeers, especially with the Band’s hound-dog chorus behind him. (Listen to “Nothing Was Delivered” or “Ain’t No More Cane (Take 2)” for evidence.) He was comfortable and confident in stretching beyond his usual vocal modus operandi.

This new boldness produced “Basement” songs with surprising emotional range and depth. The ramshackle musical marvels range from joyful larks to more serious explorations of love, faith and life. “Million Dollar Bash” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” are fun, carefree ditties while songs like “Tears Of Rage” or “Too Much Of Nothing” are major works that are just coming into being with ornate power and lyrical gravitas.

This seriousness at times crosses over to take on unanticipated religious overtones. Songs like “I Shall Be Released” and exquisite but incomplete song sketches like “Sign On The Cross” and “I’m Not There” clearly point the way where Dylan was to go with his next album, “John Wesley Harding.” Each song’s acoustic-guitar strum and the church-ified piano and organ combo was a bed for the lyric’s moralizing stories and spiritual imagery.

But, just as listeners might be nailing down Dylan and company’s purposes, they seemed to change the game plan. Other tracks, like “Goin’ To Acapulco” or “Quinn The Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn),” start with an screwball premise but showcase wonderful melodies. These and other raw tryouts suggest that lyrical silliness or lustiness walked hand in hand with Dylan’s fascination with righteousness.

Even goofy songs — tracks that are the musical equivalent of a recorded crank call or incidents when the drugs were apparently a little too strong — were treated with a seriousness and thoroughness that belie their ridiculousness. Dylan and Manuel are intent on making each other laugh with dueling silly voices on “I’m In The Mood For Love.” The pair then try to find something worthwhile between guffaws on the improvisational “See You Later, Allen Ginsberg,” giving it two takes before leaving it for never again. Only “I’m Your Teenage Prayer” seems to outgrow its dorky origins to become something approaching amazing. Dylan’s steady strum and deadpan vocals are trying to keep it all together while Manuel intones like a deadpan Frank Zappa with alternative rhymes — “I’m your teenage hair!” — before Dylan surrenders and lets Manuel and Danko’s vocal mugging destroy anything that he hoped to build.

Even old favorites like “Blowin’ In The Wind” and “One Too Many Mornings” were tried out in an attempt to discover an entirely new attack. “Blowin’ In The Wind” was recrafted as a smoldering, South Side blues rager. In the case of “Morning,” Dylan mostly keeps the arrangement the group had worked up for the 1966 tour, but with a few important tweaks. First, Dylan has Manuel beautifully crow the first verse (even though Dylan takes the rest of the song and is obviously more confident playing with the material.) He also adjusts Manuel and Danko’s ethereal backing vocals to make them less urgent and more like a church group. Hudson’s organ playing reinforces the religious vibe with stately swells to create a Sunday-morning ambiance despite Robertson’s Saturday-night blues licks. (For the most important performances on the new box set, read this related article.)

As new songs emerged, Dylan also seemed in a generous mood and collaborative mindset. While Dylan was developing his own song ideas, he also wanted to educate his disciples on the art of songwriting and ground them in the musical forms that weren’t typically a part of their routine in the dives, bars and honky tonks of North America. Robertson said he could tell Dylan had rehearsed many of the songs they played before arriving in Big Pink. Likewise, writer Greil Marcus, who wrote a convoluted essayist’s book about “The Basement Tapes,” has spoken about how he learned that Dylan had asked folk-musicologist and New Lost City Ramblers leader John Cohen to bring banjos and dulcimers up to Woodstock to inspire/educate the former Hawks.

That sharing extended even into true partnerships. For the first time in his career, Dylan shared co-writing credits — with Manuel and Danko — that yielded extraordinary results: “Tears Of Rage” and “This Wheel’s On Fire.” Throughout the recordings, Dylan can be heard encouraging Manuel to take verses or lead the band or pitch him rhyming couplets. A typewriter stationed in the living room above the basement (Hudson called it the writers’ room) likewise offered a place to trade ideas.

And so, there was a coaching and instruction going on that would serve the Band members well for the early part of their career away from their boss. One could argue only when they strayed from the spirit of Big Pink did rock-star cliches degrade the group’s abilities and rob them of reaching their full potential.

What’s also most remarkable about these songs is that these were in many cases something on the side as compared to Dylan and the Band’s own separate songs being prepared at that time. Many overlook the fact that Dylan wrote much of the material for “John Wesley Harding,” his last great ‘60s masterpiece, at the same time that he woodshedding with the former Hawks during the afternoons. Oddly, no one has ever sought or even spread rumors that Dylan demo-ed any of the “Harding” songs with the Big Pink guys. (Robertson has said that around that time, Dylan asked if he and Hudson wanted to put overdubs on the album, but the guitarist urged him to keep those songs’ streamlined production.) The Band, meanwhile, was compiling material for “Music From Big Pink,” which they recorded in early 1968.

The lines separating all of these projects weren’t once so clear. As the box set’s liner notes suggests, this release was an attempt to completely document the “Basement” period. In the case of the 1975 double album — 24 songs in total – were compiled by Robertson and issued to mass acclaim. While critics hailed the material, some grumps took issue with the number of Band-only recordings that appeared on the album, arguing that it supplanted Dylan material. (Missing were such fabulous songs as “I Shall Be Released,” “The Mighty Quinn,” “Sign On The Cross” and “I’m Not There.”)

Their grumblings only grew in subsequent years as stories came forward of how Robertson had included songs that weren’t even recorded in the basement (but in fairness to Robbie, whose origins date from the period), added overdubs to some “Basement” tracks prior to release and in a couple of cases, completely re-recorded two or three songs for final inclusion. The criticisms are fair, if in most instances, the opinions of obsessive Dylanologists. While “The Basement Tapes” double album still serves as an excellent entre to this material, one can’t escape the idea that there was unfinished business here.

If there are any criticisms with this box set, it’s the collection’s scholarly mindset and specifically, how the Band-only “Basement” material has been excised completely. Gone are any stuff the Band tried out when their employer was elsewhere (even though the songs appear interspersed on the actual tapes with the Dylan material) or oddball sessions the guys did with ’60s novelty artist Tiny Tim. In particular, all those controversial Band songs that appeared on original double album have been removed. Top-notch songs like “Orange Juice Blues (Blues for Breakfast),” “Rueben Remus,” “Katie’s Been Gone,” “Long Distance Operator,” and “Yazoo Street Scandal” were likely recorded as demos or studio outtakes ahead of “Music From Big Pink,” but probably not in Big Pink or sessions in which Dylan participated. Three other “Basement Tapes” album cuts — “Bessie Smith,” a Helm-sung version of “Basement” track “Don’t Ya Tell Henry” and a sublime Band take of “Ain’t No More Cane” — were material from the era, but allegedly recorded in 1975 to boost the group’s profile on the joint release. (Rumors of another Band box set focused on the outfit’s early years are the only salvation for this jettisoned material.)

Born In The ‘Basement,’ Songs’ Influence Went Global

Surely, not even rock’s most popular stars heard all of the “Basement” music, but they sure understood what it meant. Hearing this music pushed many to junk their sitars, ditch the trappings of psychedelia and let their beards grow long.

Under the “Basement” influence, the Beatles recorded “The White Album,” “Abbey Road,” and particularly “Let It Be.” After embarrassing themselves by trying to copy “Sgt. Pepper,” the Stones realized they could embrace their fascination with Southern music to fill their great run of albums, like “Beggars Banquet” “Sticky Fingers,” “Let It Bleed” and “Exile On Main Street.” The always opportunistic Byrds recorded a full-blown country album while the Dead and Crosby, Still & Nash were smitten because a folksy sound allowed them to return their own roots. Generations of musicians afterward likewise realized genres weren’t lines of demarcation, but measures of degrees. This allowed industry-imposed categorization to bend and break for artists bold enough to straddle the lines.

And while musicians heard this music, the fact that these recordings were verboten left a ravenous public with no alternatives until rock’s first bootleg, “Great White Wonder,” plundered many “Basement” songs and essentially created the recording industry’s black market. It isn’t too much of a stretch to trace the origins of Napster, BitTorrents and file downloading to this very point in time.

Whether it’s the evils of file sharing or cruddy country-rock performers (Poco, Billy Ray Cyrus, among others), “The Basement Tapes” deserve all of the credit and none of the blame for what came after. It would be hard to imagine today’s pop music without them. If critic-created hype has always threatened to exaggerate anything that Dylan and the Band collaborated on, these recordings are the one instance where — defects and all — no hyperbole is an overstatement.

That Dylan and the guys would feel gun shy about releasing this “basement noise” is an understandable impulse, if a mistaken one. “Nothing is better, nothing is best,” Dylan cries on “Nothing Is Delivered,” but if we extend what that lyric means to “The Basement Tapes,” he’s proven wrong again and again. These songs were a corrective action for the music world that they never thought would escape the basement’s concrete walls. They offered American music back to those who’d overlooked its glories and even expanded upon that tradition with a few Dylan masterpieces.

Now that these songs have been delivered, it’s only right to see them take their deserved place in American musical history. Born out of tradition, “The Basement Tapes” are destined to become part of it.