Beau Jammes sat inside Dodge Correctional Institution, a maximum security prison in Waupun. It was late March 2018, and he was 25 years old.

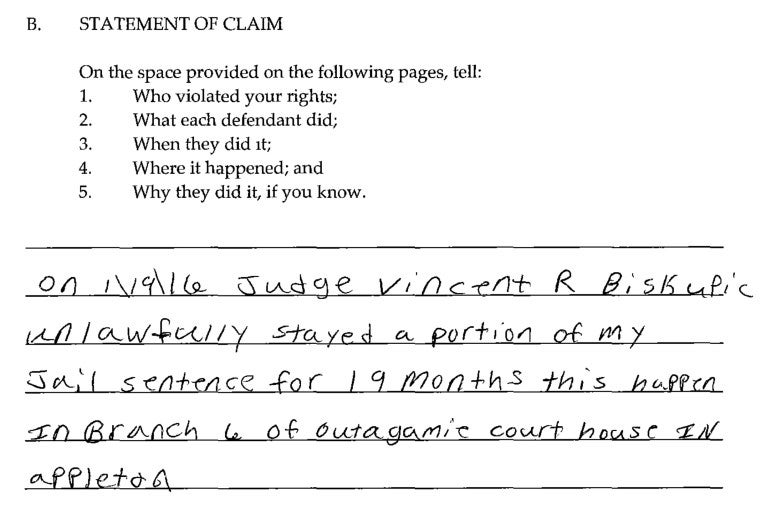

Jammes looked at the form before him, picked up a pen and began to write: “Judge Vincent R Biskupic unlawfully stayed a portion of my jail sentence for 19 months.”

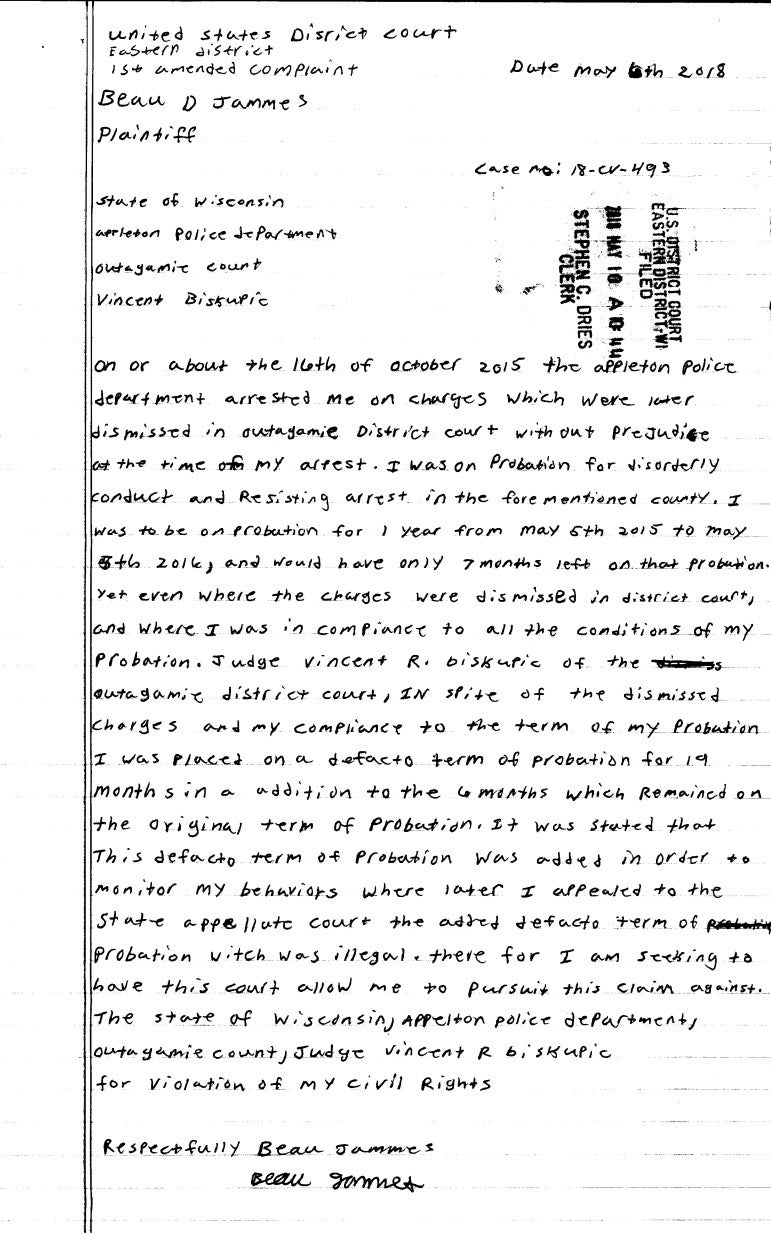

The complaint to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin requested lost wages, employment and housing, along with “mental stress” and “pain and suffering.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The young man elaborated later in an amended complaint. On lined paper in a dark, squat script, he wrote that the Outagamie County judge had placed him “on a de facto term of probation … in order to monitor my behaviors.” It was, Jammes alleged, “illegal.”

Jammes’ case was among 31 such cases between 2014 and 2020 in which a Wisconsin Watch investigation found Biskupic offered to stay or furlough defendants’ jail time if they complied with his conditions.

A stay formally pauses or postpones a person’s sentence. State law restricts judges’ ability to issue them. A furlough allows an incarcerated person to temporarily leave confinement to attend events such as funerals.

Biskupic’s supervision departed from traditional probation overseen by the Wisconsin Department of Corrections. It is not spelled out in state law and has no sunset period. Several attorneys said they consider these arrangements advantageous. Others argued they make defendants vulnerable to uncertainty through shifting demands and protracted timelines. Some legal experts questioned whether the practice is lawful.

Wisconsin Watch found Biskupic ordered four defendants arrested for failing to show up for these legally dubious review hearings.

Jammes objected to Biskupic’s lengthy supervision and shifting demands. In filing a federal lawsuit, Jammes was among a rare few defendants who challenged Biskupic’s arrangements. A magistrate judge dismissed Jammes’ claim, saying judges generally have “absolute immunity” when performing official duties.

Biskupic did not answer detailed questions about his practice, writing in a statement that state Supreme Court rules limit his comment on specific cases. He noted the cases in question “resolved mostly in the four-year period of 2015-2018” — the latter being the same year Jammes filed his complaint. Biskupic did not answer a question about whether he has stopped the practice.

Biskupic’s attorney, Daniel T. Flaherty of Godfrey and Kahn, provided information on some defendants’ additional criminal records, like Jammes, and he defended the judge’s actions.

Biskupic’s Offer Welcomed

At first, Jammes and his lawyer, Gary Schmidt, a seasoned private attorney appointed by the state public defender’s office, felt optimistic — even grateful — for the stay Biskupic offered.

They appeared before the judge in December 2015, after the DOC revoked Jammes’ probation primarily for a weapons violation — later proven unsubstantiated. In Wisconsin, when people get revoked from probation, they generally are sent to jail or prison to serve their sentence.

Jammes faced up to two years in prison for his original crime: Resisting an officer as a repeater. The DOC recommended six to nine months. The prosecutor recommended that range’s higher end.

“I will do anything to prove to you that this is not what it is,” Jammes said. “Even if you have to put me back on probation, if you want me to prove it to you. I’m not this person.”

Under Wisconsin law, circuit judges cannot reinstate probation after revocation. So Biskupic gave Jammes a year in the Outagamie County Jail — “a straight jail sentence” with work release and ability to earn good time. But then, he raised a possibility that Jammes’ attorney had neither requested nor ever experienced.

“This isn’t a deal, but this is what I’m going to offer you,” Biskupic prefaced.

Biskupic explained that if Jammes kept a job and provided a letter sharing his progress, the judge “might stay some of that remaining time.” A temporary stay would freeze Jammes’ jail sentence, letting him out while the remaining incarceration loomed; a permanent stay would erase the remaining days.

At the hearing, Biskupic did not explicitly state which he would issue.

“You stay focused and do the things that you have the ability to do, this one-year sentence can get reduced based on a petition and a follow-up hearing,” he said.

A month later, Schmidt filed a motion asking Biskupic to reduce Jammes’ sentence to time served, meaning his incarceration would end. In the motion, Schmidt emphasized that Outagamie County prosecutors had found no evidence of the crime for which he was revoked and had dropped their charges.

Biskupic convened a hearing. But instead of modifying Jammes’ sentence — a standard practice spelled out in state law — he reverted to his initial offer and temporarily stayed his jail time.

“You are not completely where I want you to be on stability, but you are going in the right direction. To help encourage you in the right direction I am going to give you a break,” the judge said. “That doesn’t mean (the jail sentence) goes away. It’s just put on hold.”

Biskupic ordered Jammes to follow several conditions: A full-time job, counseling or addiction meetings, sobriety, take his medications, continue GED classes and stay out of trouble. They’d review his status in March, several months later.

But Biskupic warned, “If I hear that you got arrested in the meantime, I am going to get a warrant for you to come back here even earlier.”

Jammes told the judge the arrangement sounded fair. Neither Schmidt nor the prosecutor objected.

“I thought it was an opportunity for him to stay out of jail,” Schmidt said in an interview. “(Biskupic) was dangling a carrot in front of Beau to try to encourage him to be employed and to get his GED so that he could get better jobs and survive better in society.”

Jammes said in an interview that he was initially pleased.

“I got to save my home. I got to save what I’ve earned, what I’ve worked so hard for, and I was kind of grateful.”

‘The Judge Was A Probation Agent’

But Jammes’ outlook darkened as time dragged on. The March hearing yielded another — “one more review” — plus a new directive: follow his landlord’s rules. But then, Biskupic again scheduled “one last review date.” And that hearing yielded another. Even more followed.

“The fact that it continued on for months and months … It pissed me off and everything,” Jammes said. “I felt like I was still locked up. I didn’t feel free.”

Biskupic summoned Jammes for a total of seven review hearings — a purgatory that lasted around 19 months. Through it all, Jammes remained tethered to Biskupic. Slipping up could trigger a return to jail.

Eventually, Jammes said he gave up trying to follow Biskupic’s rules. He got arrested yet again for disorderly conduct and incarcerated by another Outagamie County judge. Biskupic called Jammes in and lifted the stay. After more than a year and a half under Biskupic’s gaze, he at last learned his fate; he was back in jail.

In retrospect, Schmidt thinks Biskupic went too far.

“I think the judge wanted to keep Beau under his thumb,” Schmidt said. “The judge was a probation agent.”

After Biskupic sent Jammes back to jail, Schmidt challenged the judge’s authority to craft the unconventional sentence. Biskupic requested that he draft a legal memo on “how long of a furlough is allowed.”

Court records show he never filed the memo. “My best guess,” Schmidt said, “is that I decided not to appeal because it would be a drawn out process, and Beau’s case would have ended before the matter got in front of the appellate court.”

Probation — The Usual Way

In Wisconsin, judges impose probation which the DOC monitors and enforces. Through this so-called community supervision, the DOC holds people accountable for law-breaking without locking them up. The DOC says it is designed to “strengthen the family unit, encourage lawful behavior, and provide local treatment programs.”

The agency lists 18 standard rules for all probationers, which emphasize following the law, public welfare and rehabilitation. Agents also set specific conditions, as do judges, who have broad discretion to set any “which appear to be reasonable and appropriate” according to law. Throughout probation, participants must regularly check in with the DOC agent assigned to monitor their behavior.

Judges may require a person to return to court to provide updates; Milwaukee’s Domestic Violence Courts have a longstanding policy of compulsory probation review hearings. While these resemble Biskupic’s mandatory review hearings, there’s a crucial difference — the person is on probation, and a DOC representative attends.

According to the Wisconsin Criminal and Traffic Benchbook, which provide courts with legal guidance, judges should only forgo probation if they deem someone likely to commit future crimes, outside “rehabilitation services (have been) exhausted” or community supervision would “unduly depreciate” the crime’s gravity.

“Often, probation is sort of the default sentence,” said Cecelia Klingele, associate professor at University of Wisconsin Law School, where she teaches criminal law, including sentencing.

Pages of single-spaced statutes and departmental rules detail how Wisconsin’s probation functions. These set out the maximum initial lengths, varying by crime, and articulate rigid processes and limitations shaping how judges may extend probation — and how the DOC may revoke it.

The law also explains that, technically, probation is not a sentence, but rather a sentence alternative.

Wisconsin places people on this form of community supervision at a higher rate than it locks them behind bars. But while probation is intended as an alternative to incarceration, it can facilitate a “pipeline” to imprisonment.

Klingele explained that rule violations can result in incarceration, “whether or not they’re relevant to the individual person and case.” As a result, she said, “probation is not nothing.”

DOC spokesperson John Beard said via email: “Revocation decisions depend on the violation and the individual’s risk and overall adjustment to supervision. Typically, only serious violations lead to revocation. … There are many possible responses to violations that include interventions, sanctions and alternatives to revocation.”

In Wisconsin, as elsewhere in the United States, strict requirements over long periods mean a significant portion of people on community supervision — an umbrella term for probation, parole or extended supervision — become incarcerated without committing new crimes.

A report from the Columbia Justice Lab found that in 2017, over one-fifth of adults in Wisconsin prisons landed there for violating a technical rule. In recent years, Wisconsin’s community supervision regime has sustained scrutiny and calls for reform.

“I think that courts and litigants are often frustrated by the constraints of the law and the ways in which probation in many ways has become a trap for the unwary,” Klingele said. “And I know DOC is making great efforts to try to improve supervision practices, streamline rules of supervision and address some of the criticisms that have been made about probation.”

But, she added, “It is true that the way we structure these standardized rules for people makes it easy for us to end up punishing behavior that actually isn’t even criminal in and of itself. And that often is indicative of poverty and lack of opportunity as much or more than it is about deviance.”

‘Probation … Through The Judge’

It’s in the shadow of this probation system that Biskupic operates something like it.

Of the defendants who took Biskupic up on his offer, almost all had been revoked from probation like Jammes. They faced almost certain incarceration, and having been extended a chance at freedom — no matter how tenuous — seized it.

“I thought maybe the judge was just going to run it for a couple of months to make sure that Beau stayed out of trouble for awhile, and then that would end it,” Schmidt said. “But he kept extending it and extending it.”

Over 19 months, Biskupic measured Jammes against an elusive benchmark: “stability.”

“I will decide what stable means, whether it’s a few weeks, a few months,” Biskupic said. Transcripts indicate the concept encompassed nearly all aspects of Jammes’ life, including work, housing, friends, health and — especially — education. But Biskupic never defined it, and its boundaries seemed to shift.

“We’re not going to keep this going forever,” he told Jammes in April 2017. “But I want to see some stability from you.”

At one hearing where Jammes appeared without his lawyer, the judge raised the bar. The stay’s original order said Jammes merely had to continue to make progress in the GED program. Now, Biskupic was telling him he had to get his GED.

“I know Mr. Schmidt still isn’t here; but it’s not like I’m doing anything of evidentiary value that’s adverse to your interests. The GED is going to open some doors for you,” Biskupic said. “So what I’m looking to do is give you one last review date. If you are doing OK and you have this GED, we can end this.”

Jammes, who says he has dyslexia, never got his GED. The transcripts indicate he worked toward it for months through courses and practice tests.

“I had everything going for myself, but he continued and continued and continued ’cause I didn’t have my GED.”

Jammes said that, in effect, the stay required him to “continue probation, just through the judge.”

And it meant the case lasted longer. Had Jammes just served the time Biskupic gave him, he could have left jail and closed his case in July 2016. But the stay caused a delay; Biskupic ordered Jammes back to jail in September 2017.

“I don’t think there is any actual statutory authority for the judge to act that way,” Schmidt said. “I think he was just using his discretion, what he thought was helpful for Beau. (But) I think once the maximum term for any kind of probation or confinement expires I think the court’s jurisdiction ends.”

He added, “There was no way to know how long this judge was going to continue to run this on.”

Nora Demleitner, professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law in Lexington, Virginia, says this type of court action can prolong involvement in the criminal justice system for people committing low-level offenses.

“This sentencing strikes me as a prime example of net-widening,” said Demleitner, who reviewed several cases at Wisconsin Watch’s request. “Some of these people, it looks like they could have been just discharged. But he (Biskupic) is hauling them back in and then sometimes putting them, it sounds like, it’s under quite a bit of pressure or even sends them to jail.”

‘Probation Is Not Permitted’

In at least two cases, the state public defender’s office appointed counsel to represent people at Biskupic’s self-styled review hearings while characterizing the nature of the case as “probation modification/extension.” But court records show neither of those defendants were on probation at the time.

The state public defender’s office declined to explain the discrepancy. Spokesperson Willy Medina said in a statement: “Ethical requirements and the passage of time make it very difficult for SPD to go through the specifics of past cases.”

In 2016, an Outagamie County assistant district attorney motioned to lift a stay issued by Biskupic “based on the revocation of his probation, the fact that this is a sentence after revocation and probation is not permitted.”

In an email, Flaherty said this defendant “was never placed on probation to the court,” but rather was “monitored through his various treatment programs and through the efforts” of a substance abuse specialist contracted with the county. However, he acknowledged: “At review hearings, the court received updates on the defendant’s progress with treatment programs.”

Flaherty also characterized the time spent out of jail as a “furlough,” rather than a stay. Though a slippery term, multiple legal experts said a furlough is a temporary, authorized absence from an incarcerative institution, typically for events like funerals.

‘Legal Fictions’

About two dozen legal experts consulted by Wisconsin Watch and WPR had a wide range of views about Biskupic’s use of review hearings. Some said the practice is legal, some called it a gray area and some said it has no basis in state law. Others had never heard of it before.

“The little secret of criminal justice is sometimes we do legal fictions because it benefits the client and we all think it’s OK,” said Brandt Swardenski, a private defense attorney and former state public defender. “Imposing and staying sentences and having someone come back in for reviews … gets a little fuzzier because there’s limited situations when a court’s supposed to impose and stay a sentence.”

The state public defender’s office said in a statement that statutes do grant judges “broad discretion at sentencing” but failed to elaborate.

But Michael O’Hear, a professor at Marquette University Law School, said in an interview, “We’ve got case law, apparently, that says once the judge imposes the sentence that the judge simply needs to turn the matter over to the executive branch of government for implementation of the sentence, unless one of these (few) recognized exceptions apply.”

Some See Benefits In Biskupic’s Practice

Nevertheless, some attorneys and defendants subjected to the practice said they considered it helpful and that Biskupic acted with good intentions.

In many cases, Biskupic stayed incarceration so people could attend drug or alcohol addiction treatment.

One defendant, Kristen Gurholt, said she was grateful that Biskupic stayed her jail sentence so long as she wrote a letter to her son apologizing for the behavior that landed her behind bars. She called Biskupic “amazing,” adding, “”I don’t have a single bad thing to say about him.”

Former state public defender Amanda Skorr, who now works as a private defense attorney, said Biskupic’s supervision was less restrictive than probation supervised by the state DOC.

“He’s not depriving people quite as much of some of their rights and liberties that they (would) have if he were to put (them) on regular probation,” Skorr said in an interview. “It’s not as awful as it sounds because probation to the court is really very, very different than probation to a probation agent.”

However, she acknowledged: “The risk is you don’t know when it’s going to end and what the consequence is if you don’t do it.”

Said Craig Mastantuono, a private defense attorney and adjunct law professor at Marquette: “If a judge routinely engages that practice without clear statutory definition, then you’re really subject to that judge’s discretion without … guardrails. That could be a dangerous thing if the discretion utilized becomes more outlandish and judges are making up wish lists without much statutory guidance for what they want to see accomplished.”

Schmidt, Jammes’ attorney, called the case “an example of the court overreaching.”

“There should be some status completion and conclusion here,” he said. “Beau never got to that point. There was always something more that the judge wanted.”

Phoebe Petrovic is a Report for America corps member. This piece was produced for the NEW News Lab, a local news collaboration in Northeast Wisconsin. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, Wisconsin PBS, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.