In the world of health care, titles matter, and a dispute over how to classify nurses with advanced degrees in Wisconsin has many of the state’s health care groups at odds.

Groups representing nurses are making another push to create a new license for advanced practice registered nurses who perform many of the same services as physicians in Wisconsin.

Doctors’ groups remain opposed but say this could be the year the two sides agree to a compromise.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The back-and-forth is not new in Wisconsin. Gov. Tony Evers vetoed a similar bill last session, citing a lack of agreement in Wisconsin’s medical community. But nurses say the debate has taken on added urgency as a wave of physician retirements and an aging population has led to shortages of care, particularly in rural areas.

The bill lawmakers are considering this year would create a new license for advanced practiced registered nurses, or APRNs, in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Nurses Association says about 8,000 nurses would qualify.

While the plan spells out a variety of requirements people would have to meet for the new license, at its core, nurses who testified at a recent public hearing on the bill say one provision is key. It would mostly lift a provision in current law that requires advanced practice nurses to maintain oversight agreements with physicians.

“In essence, a permission slip to provide care,” said Tina Bettin, who has been a nurse practitioner for 35 years, including 30 years in rural areas.

Nurses say oversight agreements are more than just an annoyance. Due to doctor shortages, they say it can be hard to find physicians to sign oversight agreements at some clinics, particularly in rural Wisconsin. Should a doctor suddenly leave or retire, they say it can threaten a nurse’s clinic. Some doctors also charge fees that nurses argue are either too steep or unnecessary.

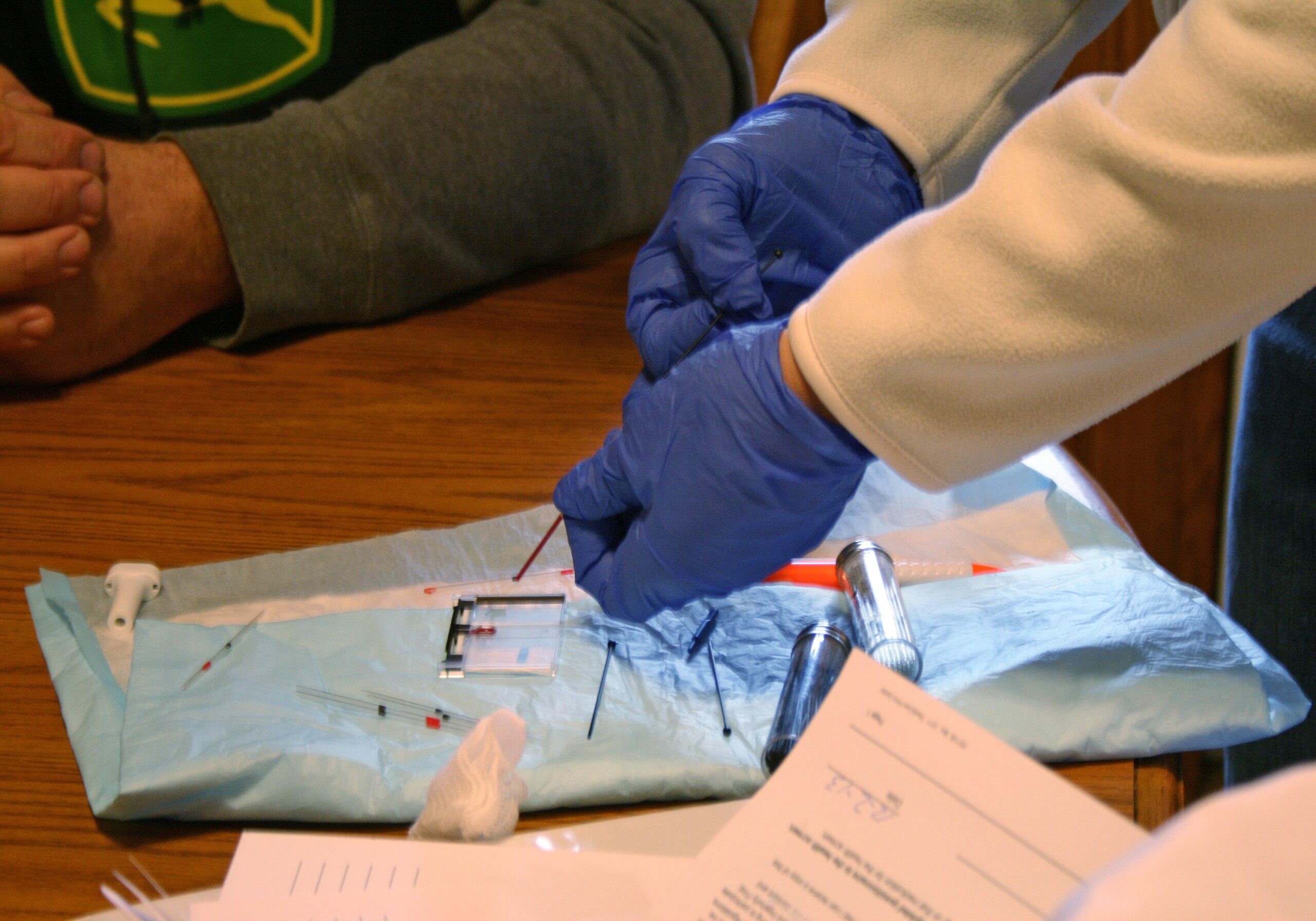

Terri Vandenhouten has been a family nurse practitioner for 27 years and was a registered nurse for another 13 years before she earned her master’s degree. At her rural family practice clinic in Franken, she said she performs wellness visits, physicals, and treats patients with a wide variety of chronic conditions from diabetes to depression. She uses diagnostic testing, including lab work, to prescribe treatment ranging from medications to physical therapy.

Despite her experience and expertise, Vandenhouten said her health care system pays $1,000 per month for a physician oversight agreement.

“Typically, I spend less than one minute per month collaborating with my designated physician about a patient issue,” Vandenhouten said. “And typically it’s needing his signature on a patient’s form a patient he most likely has never met.”

Advocates say 27 states and the District of Columbia have now lifted that requirement, giving advanced practice nurses more authority to practice without a physician’s oversight.

The physician oversight requirement was relaxed for the past few years under an executive order issued by Gov. Tony Evers near the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic that has since expired. Nurses say the fact “the sky didn’t fall” shows the requirement is unnecessary.

Doctors’ groups have successfully fought efforts to lift the requirement in Wisconsin. But they say they’re open to the idea this time, with some caveats.

“We have such a great health care system,” said Mark Grapentine, a lobbyist for the Wisconsin Medical Society. “But any changes that are made to the system, we want to be very cautious about.”

In addition to lifting the physician oversight agreement requirement, the bill lawmakers are considering would require registered nurses to hold an accredited graduate-level or postgraduate-level degree in a relevant field. They’d also have to maintain medical malpractice insurance, meaning most would pay into the state’s Injured Patients and Families Compensation Fund.

One potential sticking point in the bill is the years of experience required for the new licenses. The version backed by nursing groups would require two years of experience while the Medical Society wants to require four.

“What we’re trying to guard against is just brand new people coming out of nursing school or having some kind of rapid access to an APRN designation, and then starting to practice completely independently right away,” Grapentine said.

But nurses say the four-year requirement would make Wisconsin an outlier among states that offer what’s sometimes called “full practice authority” for advanced practice nurses.

“In my opinion, this four year requirement that is being discussed is just a clever way for the Medical Society to state their ongoing argument, which is advanced practice registered nurses are not physicians,” said Barbara Nichols, executive director of the Wisconsin Center for Nursing and a nurse since 1959. “Amen. We want to be nurses. And understood as nurses.”

While negotiations over the bill are ongoing, early indications suggest Evers is on the same page as the Medical Society when it comes to the four-year experience requirement. The governor included that benchmark in a proposal to license nurses he introduced as part of his budget. GOP lawmakers have since removed that provision from the budget along with hundreds of other policies.

As part of a give-and-take, the Medical Society is also asking lawmakers to approve a separate bill that would ban people who are not licensed physicians from describing themselves with terms like “medical doctor” or dozens of other titles. Grapentine told lawmakers “credentials matter” when it comes to health care, and there’s confusion right now among patients.

“They want the expertise, the training and the education that comes from being a physician, by passing medical school,” Grapentine said. “Medical school matters.”

The “truth in advertising” bill has stoked opposition from groups representing everyone from chiropractors to nurse anesthetists to veterinarians.

“I don’t care about turf battles,” said Sen. Mary Felzkowski, R-Irma, one of the members of the Senate’s Health Committee who heard testimony on both plans Wednesday. “In fact, when you’re sitting up here, they’re very exhausting.”

Felzkowski is one of the co-sponsors of the advance practice nurses bill, which is mostly backed by Republicans but also includes some Democratic support.

Nearly 30 groups have reported lobbying on the plan, a high number for a proposal that was formally introduced less than two months ago.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.