“You have to do more than just say what you’re going to do,” said Anthony Cooper. “You have to actually do it.”

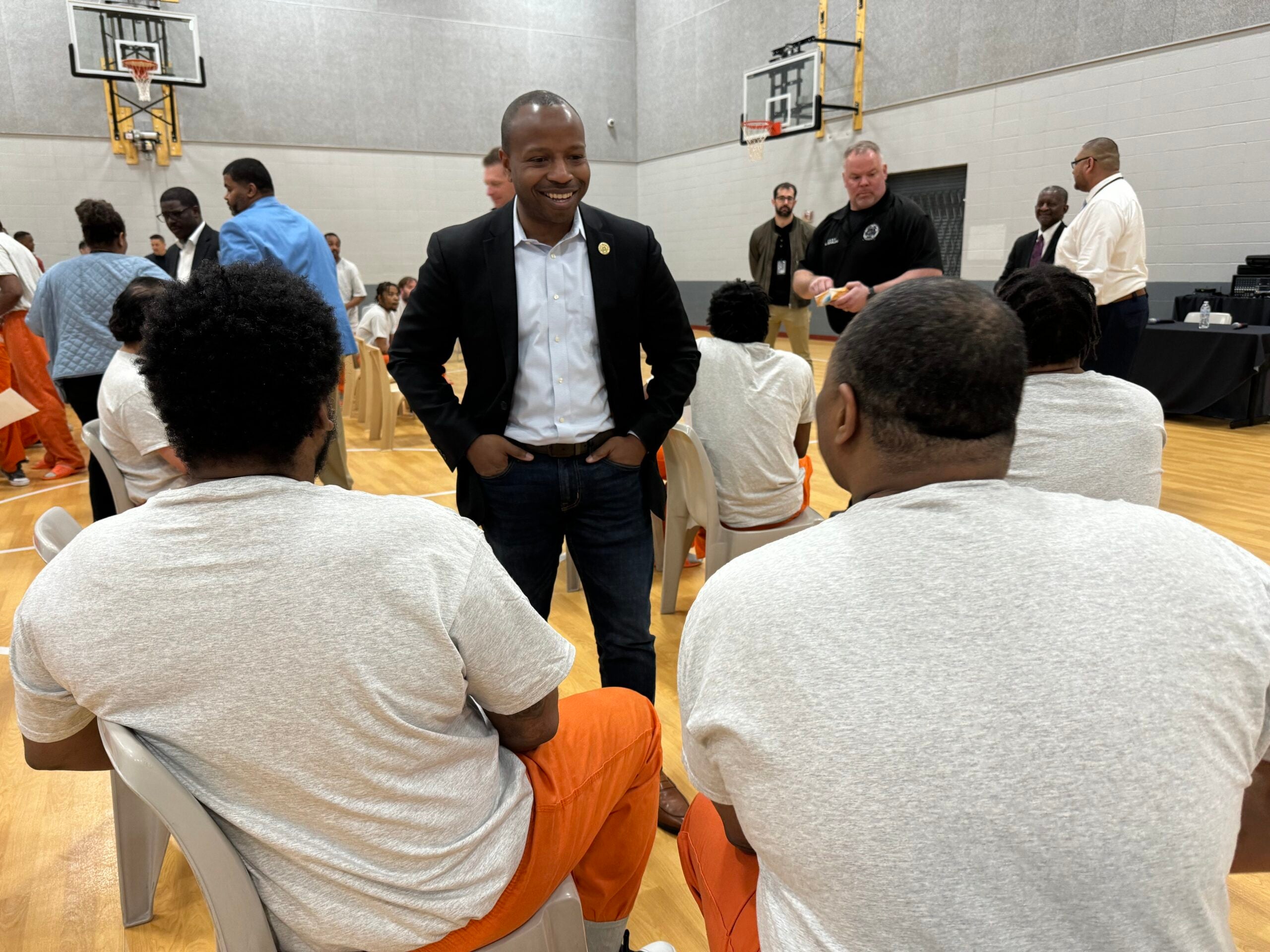

Cooper lives to help others. He coaches former prison inmates about the outside world through the Nehemiah Center Reentry Services program. He also runs an organization called Focused Interruption out of a tiny office on Madison’s south side next to the Neighborhood House Community Center.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“We work on/with violent crimes throughout our community and where there are shootings, stabbings,” said Cooper.

Focused Interruption looks to holistically reduce trauma from gun violence to the people, families and neighborhoods in Dane County impacted the most.

“We go in and then work on as far as providing intervention strategies, prevention strategies and also being able to provide support to families in the moment,” Cooper said.

In the community, Cooper is a leader. He’s the 2019 recipient of Dane County’s coveted Martin Luther King, Jr. Humanitarian Award, given to those who serve their community in the spirit of King.

“Growing up on the north side of Chicago, that was, I think, and where we lived, we had a village. Madison is my village. Because of that, I know how to act as a village,” he said. “I would have never thought I would be at where I’m at now.”

Where Cooper is now comes as a surprise to a lot of people, especially when you consider where he’s been.

“There’s an old saying,” he said, “if I knew if I knew what I know now, back then, who would I be?”

Back then, in the late 1990s, Cooper was a different man.

“When I think about how I navigated life — there was definitely some things that I wish I could have done differently,” he said. “I was a man child. Even being a man in age, there was still childlike qualities I had as well.”

Cooper recalled more about where he had been.

“I was a high school dropout. I wasn’t able to provide in the way I really wanted, to provide for my kids,” he said. “I didn’t see the light. I didn’t see that it was possible to be able to get a functioning job, to be able to have a functioning family.”

Cooper remembered earlier aspirations.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but I thought about being a nurse … getting into IT,” he said. “I always wanted to be a fireman. That was my ideal job … I would have been the best warehouse worker, I would have eventually moved up to become a supervisor of some sort.”

With all of those and more as career options, eventually Cooper took an unexpected route to quick cash.

“How hard is it to get out there on a block and, you know, if you know the right people, to go and sell drugs? he said.

Cooper became a hustling drug dealer on the streets of Madison.

“Those were some of my darkest days,” he said. “I thought then in the thick of it, like, ‘OK, I’m providing, I’m doing something … I’m trying to find a better job.’”

According to police, in February 1999, he sold heroin to a confidential informant in a parking lot outside an east side Madison restaurant and several other locations around town, including a local park. Court records show days later, he led police on a short car chase through downtown during rush hour before being arrested by Madison police.

“My mother didn’t raise me to sell drugs,” said Cooper. “My mom’s gave us all that what she could.”

At the time, he said he felt selling drugs was his only option to provide for his mother, son, and his then-pregnant girlfriend.

“I can get a job, but if a job is still leaving me struggling, I know at the same time if my pager, phone or whatever, and every time they call is $20, $50 here, $100 here — eventually then that grew. Then what happens?” Cooper said.

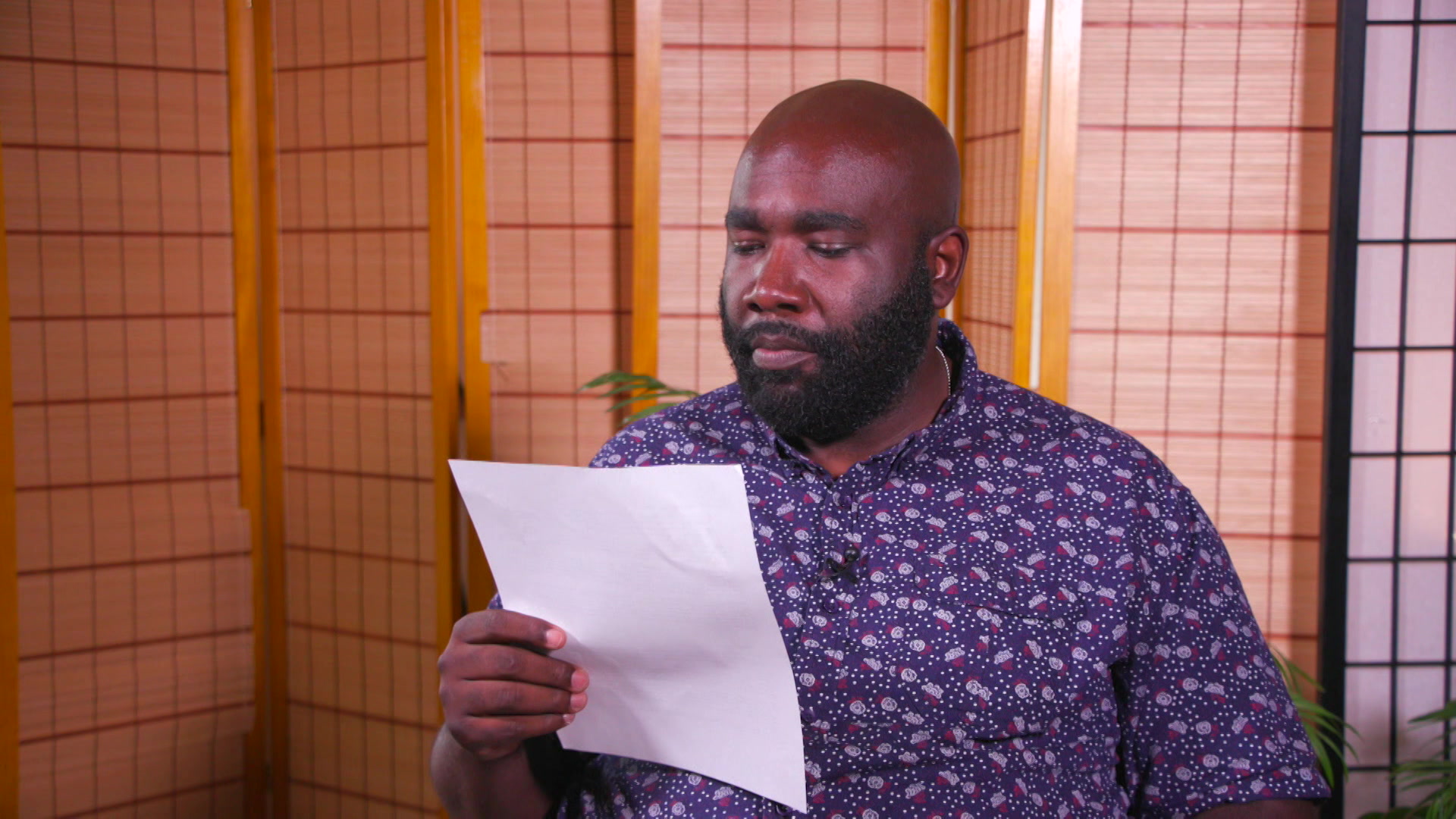

“In 1999, when I was 22 years old, I was convicted of three felonies,” read Cooper, sharing his own written words about when his drug-selling days came to an end near a street corner not far from downtown Madison.

“The things that I’m writing, isn’t writing for you all,” he said, “but for me, I will always have that memory. That’s always going to be in the core of my heart.”

Cooper sometimes wonders if getting caught may have saved his life.

“I could have got caught with more than what I had. I could have got killed,” he said. “My son is growing up without a father. My mom’s growing up, you know, she’s getting older, growing up and not having a son. My sister’s not having a brother.”

After pleading guilty, Cooper did two years in prison. Some of it in Portage, Black River Falls and the Challenge Incarceration boot camp in New Richmond.

“Nothing about prison I liked,” he said. “When someone is incarcerated, it doesn’t just affect you, it affects everyone that’s connected to you.”

But Cooper was looking to change his direction.

“When they called my name to be able to go to boot camp,” he said, “that’s the hope for me to be able to go with boot camp and successfully complete it.”

Right out of prison, Cooper said he found himself fresh out of luck in finding a good paying job. After being turned away from what he estimated to be hundreds of jobs weekly, he would settle for a gig making pizzas. Honorable work, but in his words, it didn’t pay enough to feed his family.

“When I came home, I knew I wasn’t going to sell pizzas for the rest of my life … I knew I wanted more,” he said. “I went through my own stinking thinking.”

Cooper said he fought temptations to go back to the crooked lifestyle that landed him in prison.

“The thoughts are still there,” he said. “The thought was still there.”

Cooper thought about the future for his children.

“When I look back at my sons, I never wanted my sons to come back in prison, to come and visit me there,” he said. “If I allowed them to continue to see me go back-and-forth from prison, eventually that’s going to become normal for them and then eventually they’re going to follow the same route.”

But Cooper quickly learned his status as a felon crippled his opportunities to create a better life.

“From housing, from loans … government subsidies to government grants,” he listed. “You’re still looked at as less than.”

Cooper said his criminal record seemed to always come up when he was searching for a job.

“Can you explain this to me about my background, even though it’s so many years, it’s almost a restart on life, a restart of me trying to explain and trying to convince people that, hey, that’s who I was at 19, 20 or 21, 22 is not the same person who I am today.”

Now almost 20 years out of prison, Cooper went all the way to the governor’s office seeking forgiveness and a pardon from the governor and his eight-person Pardon Advisory Board.

“None of us knew anyone that ever had a pardon,” he said, “We all knew what change looks like and they all knew the change that was within me.”

“When I was arrested, that was in 1999,” Cooper read. He wrote the words in 2019 as part of his application to the board.

“Even people that I knew from the streets say the same thing,” he said. “We’re just proud of you, who you’ve become.”

Former Madison Police Chief Noble Wray is a member of the Pardon Advisory Board, which typically meets in the finance committee room on the fourth floor of the state Capitol.

“We’ve had a number of people during COVID that have presented some very compelling cases.”

“Because of COVID, we had to do a virtual,” said Cooper. “But now it’s about what have you done to change your life around? Who are you now that you were not 20 years ago? Fifteen years ago? Seven years ago?”

Cooper’s case was one of many brought before the board.

“They’re impacted by their employment. A lot of times they’re impacted by where they can live and cannot live. There are limitations placed upon you — if you have a felony — to be able to travel outside of the country,” explained Wray.

“You can take out an 18-year-old in northern Wisconsin that decided to drive through a cornfield. Based upon the amount of damage that they create, that was a felony,” said Wray. “But they’re 18 and 19 years old, and they walk into a pardon board and they’re 55 or 56. And they look you in the eye and say, ‘Hey look, all I want to do is to be able to tell people around me that I’m not a felon.’”

Wray said the board hears directly from 25 to 30 felons each month.

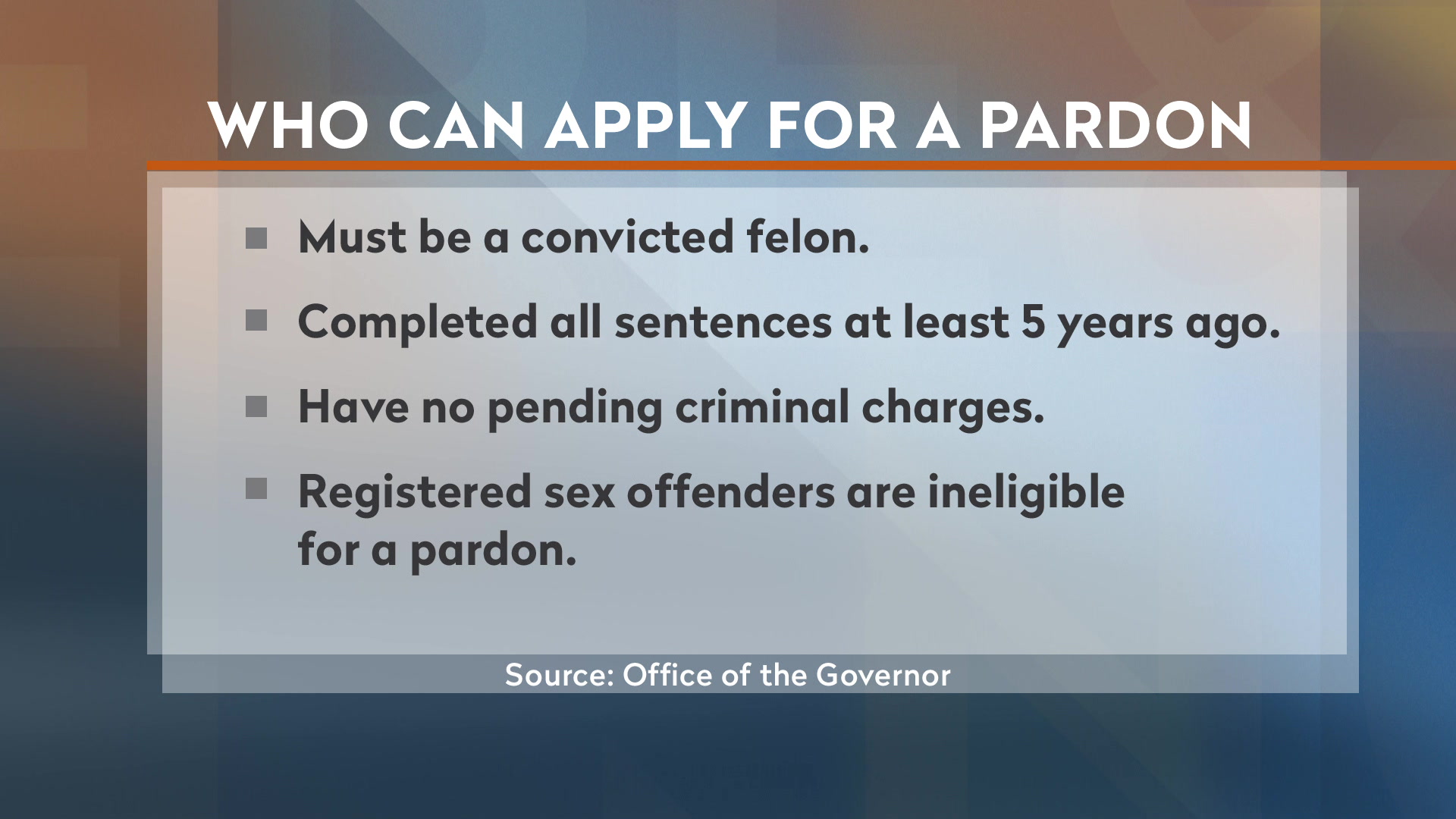

To be eligible for a governor’s pardon, you have to be a convicted felon who’s completed all your sentences at least five years ago and you cannot have any pending criminal charges or cases. Registered sex offenders are not eligible for a pardon. While the board makes the recommendations, Gov. Tony Evers has the final say.

“All that is about corrections isn’t about punishment,” said Evers. “It’s about getting people ready to reenter life outside of corrections.”

The governor explained his approach toward pardons.

“I am one of those people that believe in redemption,” said Evers. “Both my parents were in the medical field and they spent their lives trying to give people second chances physically,” he recalled, and described pardons as a way of “giving people second chances spiritually.”

The governor pursues granting pardons as a proactive solution to ease prison overpopulation.

“We have too many people in our prison right now, and whatever I can do to help those that have exited the system and are doing well in their lives, recognizing that,” said Evers.

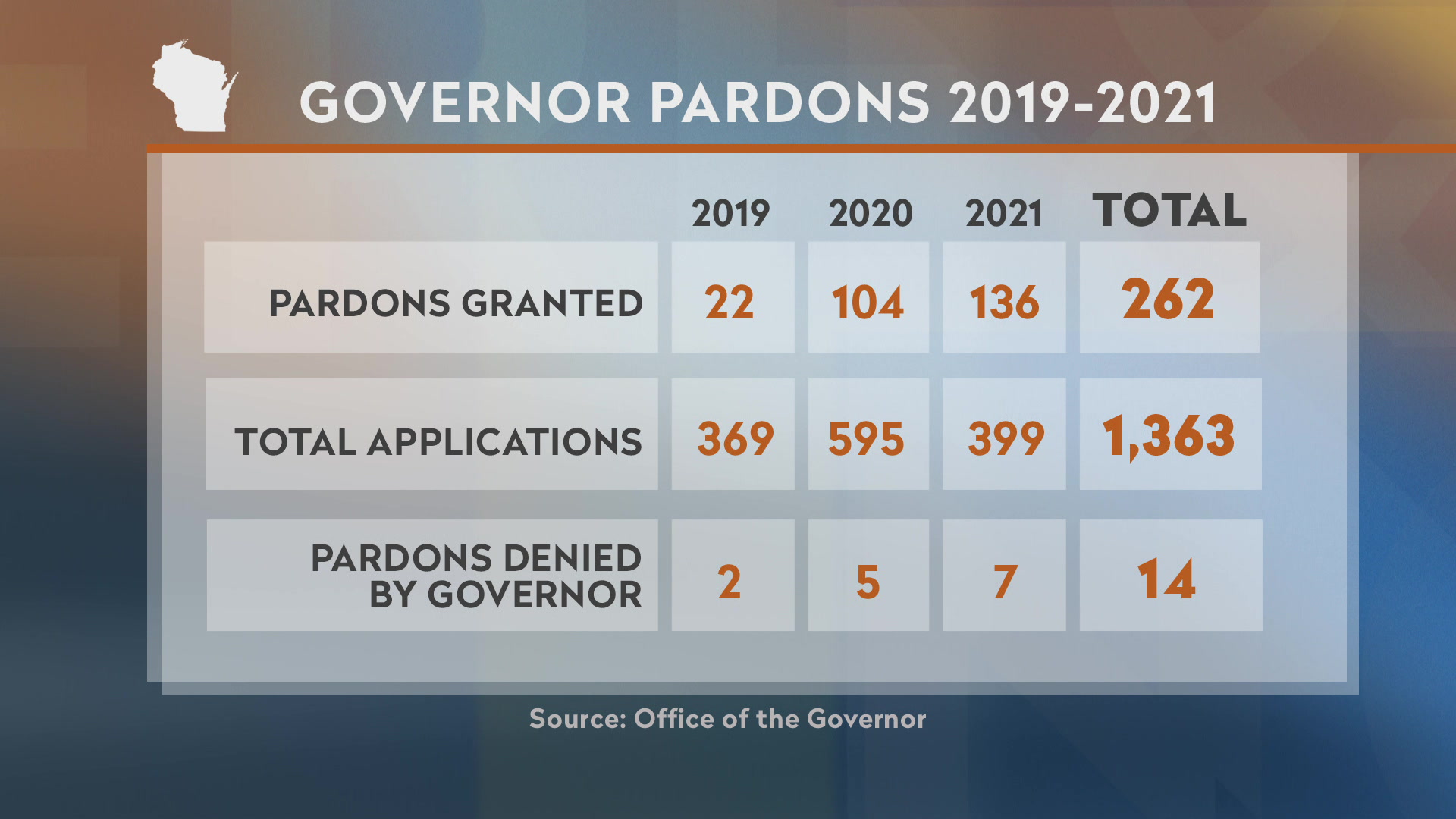

So far in just over two years in office, numbers show the governor is granting more pardons each year, approving 262 out of over 1,300 applicants and counting through August 2021, only denying the board’s recommendation 1 percent of the time.

If reelected, Evers said he will continue approving pardons. His predecessor, Republican Gov. Scott Walker, didn’t deliver a single one in his eight years as governor.

“That’s a lot of people that didn’t get that chance for many, many years,” said Evers about his reversal in this policy.

“I review every single one that’s recommended to me,” he explained. “It is one of the most heartwarming exercise that I go through as governor.”

Evers said most pardon recipients are drug offenders who have stayed clear of trouble for decades.

“Many of them, frankly, are people that these crimes were committed 20, 30, 40 years ago, and they’ve been clean for 20, 30, 40 years,” he said. “We can’t afford to throw anybody away.”

The governor said he knows it’s politically risky to grant pardons, and if someone reoffends, he expects his opponents will blame him.

“I have no doubt at some point in time, somebody will goof up,” Evers said. “There are people every day in this state and this nation that make mistakes that may end up being a criminal offense. But at the end of the day, I feel confident that 99 percent … are the right decisions.”

More than two years after submitting his application for a governor’s pardon, on Feb. 3, 2021, Cooper got news he’d anxiously been waiting on.

“Whether or not if you’re going to get it, ” he recalled, “that was the scary part for me.”

Cooper received his pardon at an important time.

“It happened on the day of my son’s birth,” he said. “I was a ball of emotions.”

Cooper said he takes his hat off to the governor for giving people a second chance.

“The fact that the governor, again, is saying, hey, you know what, let’s give this person … a new start in life. Right? That’s huge,” he said.

“If you can think of yourself as someone right now that committed a felony, and you’re asking yourself, will I ever be able to connect back with society and feel like a full citizen, a Wisconsinite in the state of Wisconsin, when you see someone like Cooper, he provides that North Star,” said Wray.

“He is hardly the only one,” said Evers. “Think about that, somebody that was just, you know, in such a bad place that they ended up being incarcerated because of years of buying and selling, and now they’re one of the leaders in their communities.”

Evers said most pardon applicants present their cases with passion.

“People are applying for this because they feel, A, they deserve it; B, they think that they can be role models in their community; and C, they feel that it can heal wounds in their family,” the governor said.

“My kids are my angels, hands down. There’s no ifs, ands, buts about that, my kids are what made me change,” said Cooper. “I had to be able to say, when I look back, I could tell my sons, I love something more than I love myself.”

“We need more Anthony Coopers,” said Wray. “People know him, they see him and they’ll look at him and say, if Anthony can do it, I can do it.”

This story was produced for WisContext, a collaboration between WPR and PBS Wisconsin.