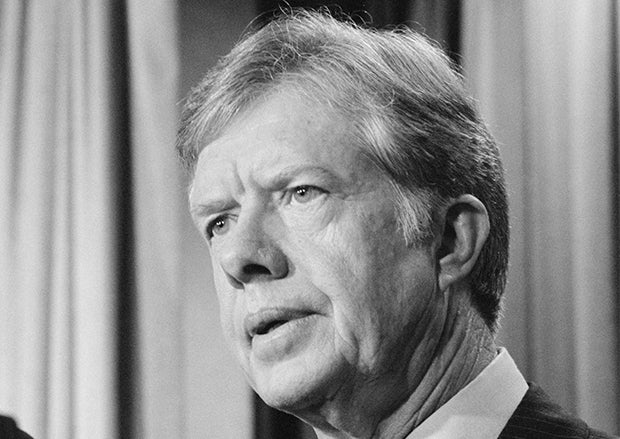

None of the broad identities attached to Jimmy Carter — beaming humanitarian, peanut farmer, UFO spotter and, at least since Ronald Reagan’s victorious 1980 campaign, ineffectual president — were on display when he visited La Crosse in September 1975. Carter faced a panel of local journalists on radio station WLSU’s “Newsmakers,” which re-aired the discussion in 2014 to celebrate that program’s 40th anniversary.

Carter was still a relative unknown in national politics in fall 1975, running in a race that would resemble the 2012 and 2016 GOP primaries in their protracted length and crowded fields. Carter announced his candidacy in December 1974 while wrapping up his single term as Georgia’s governor, becoming one of 17 candidates to seek the 1976 Democratic nomination. In Wisconsin’s primary on April 6, 1976, Carter narrowly edged out U.S. Rep. Morris Udall of Arizona, and the former governor would go on to carry Wisconsin’s then-11 electoral votes in his general-election victory over incumbent President Gerald Ford.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Despite the different roles supporters and critics have assigned him, the Carter who showed up in La Crosse was a disciplined, confident political strategist. The panel asked substantive questions about subjects like foreign policy, desegregation and grain exports. But when his answers are considered together, it suggests that Carter’s purpose more than a year before Election Day was to lay out what he clearly saw as a shrewd path to the nomination.

“I’m not interested in being vice president,” Carter said early in the interview, before rattling off details about the convention, polls and likely scenarios in early primary states.

Yes, Carter did talk policy, with enough detail to illustrate his grasp of issues like American leadership in global commodities markets. (It’s a safe guess that in a word cloud of 21st century political speeches, “bauxite” would be tiny.) But what he really talked about was his ability to walk the lines between different constituencies and political ideologies. Carter played aggressively to small-government fiscal conservative ideals, noting his record of consolidating state agencies in Georgia and even suggesting a federal balanced budget.

Carter also defended his “voluntary integration” approach to racial conflicts and opposition to busing. This stance helped him get elected in Georgia as it emerged from the Civil Rights Era, but has fueled criticism since.

And not unlike 2016 Democratic Party hopeful Hillary Clinton, Carter talked about his ties to Henry Kissinger. The difference is that Carter was more eager to criticise: “He’s a brilliant personal negotiator. I think Kissinger’s quite often inclined to create a much greater disturbance than would ordinarily exist and then have the appearance of being a savior for mankind,” Carter said on Newsmakers.

Despite his measured praise for Kissinger, Carter knew Democrats were eager to strike at a Republican Party reeling in the wake of the Watergate scandal, and he delivered the clincher later in the interview.

“I think that by the time next year comes around,” Carter said, “Ford is going to be quite vulnerable to someone like me, to someone who can tie together the various elements of the Democratic Party in a common effort.”

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.