Young children inevitably fall as they learn what they can do physically and experiment with their limits. If a fall results in a blow to the head, the child may have sustained a traumatic brain injury.

These injuries are caused by both an initial impact, such as when the head hits the ground after a fall, and a secondary impact, when the brain bounces back within the skull, causing internal bleeding and swelling. Traumatic brain injuries are the main causes of death and disability in children in the United States, accounting for more than 600,000 emergency room visits and around 18,000 hospital stays in 2013 among children aged 14 years and younger, according to a Centers for Disease Control & Prevention report.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

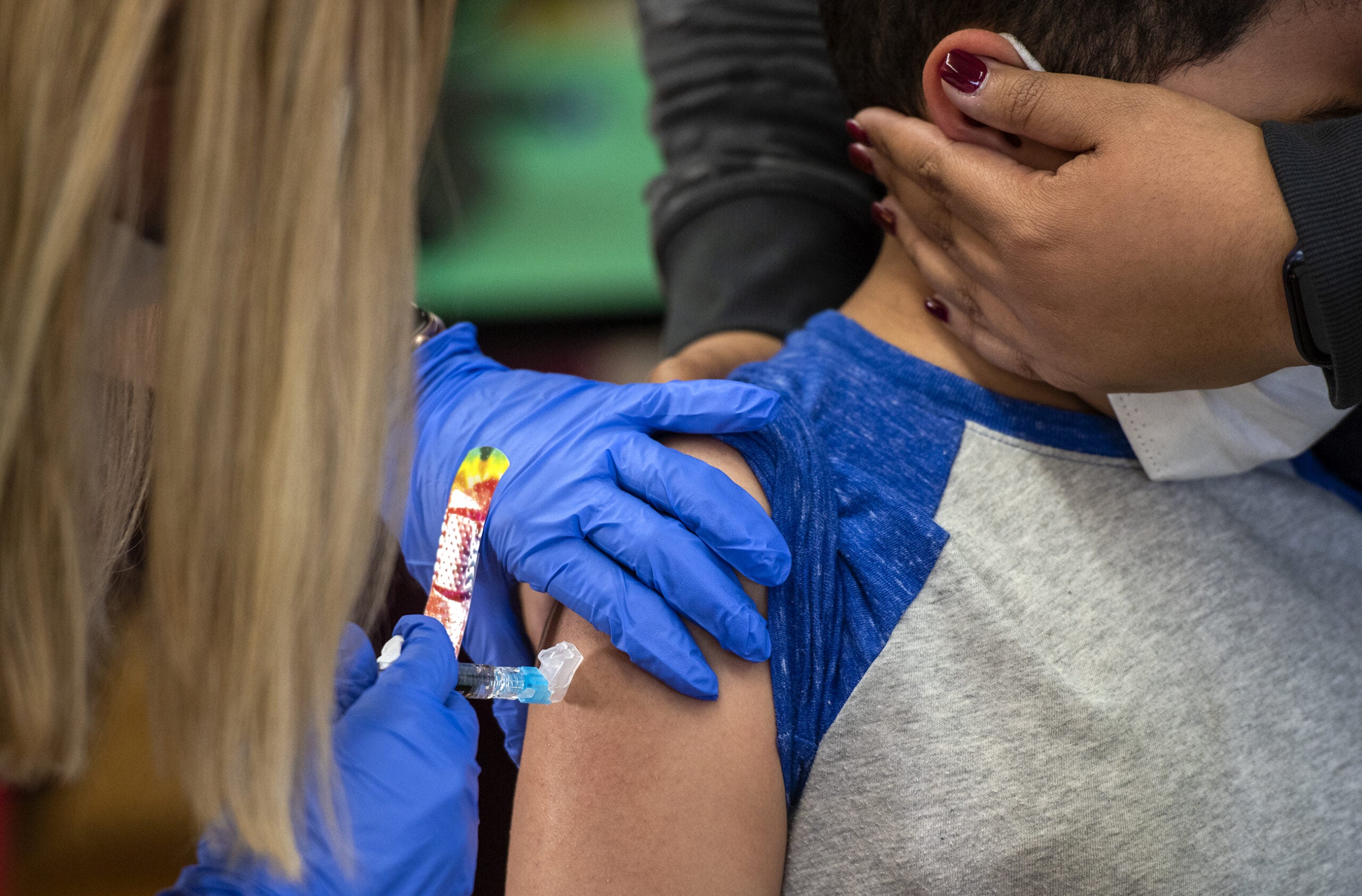

At the emergency room, health care professionals evaluate a child with a traumatic brain injury, and decide if it warrants a computed tomography scan, often called CT or CAT scan. For very young children, though, this approach might not be the best option for care. It’s an example of the innovations developed to help better care for children with disabilities, and the difficulties that can accompany them.

Walton O. Schalick III noted concerns about the use of CT scans to evaluate traumatic brain injuries in children at a Wednesday Nite @ the Lab lecture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison on Nov. 8, 2017. The talk, which looked more broadly at changing approaches to treating disabilities among children, was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s “University Place.”

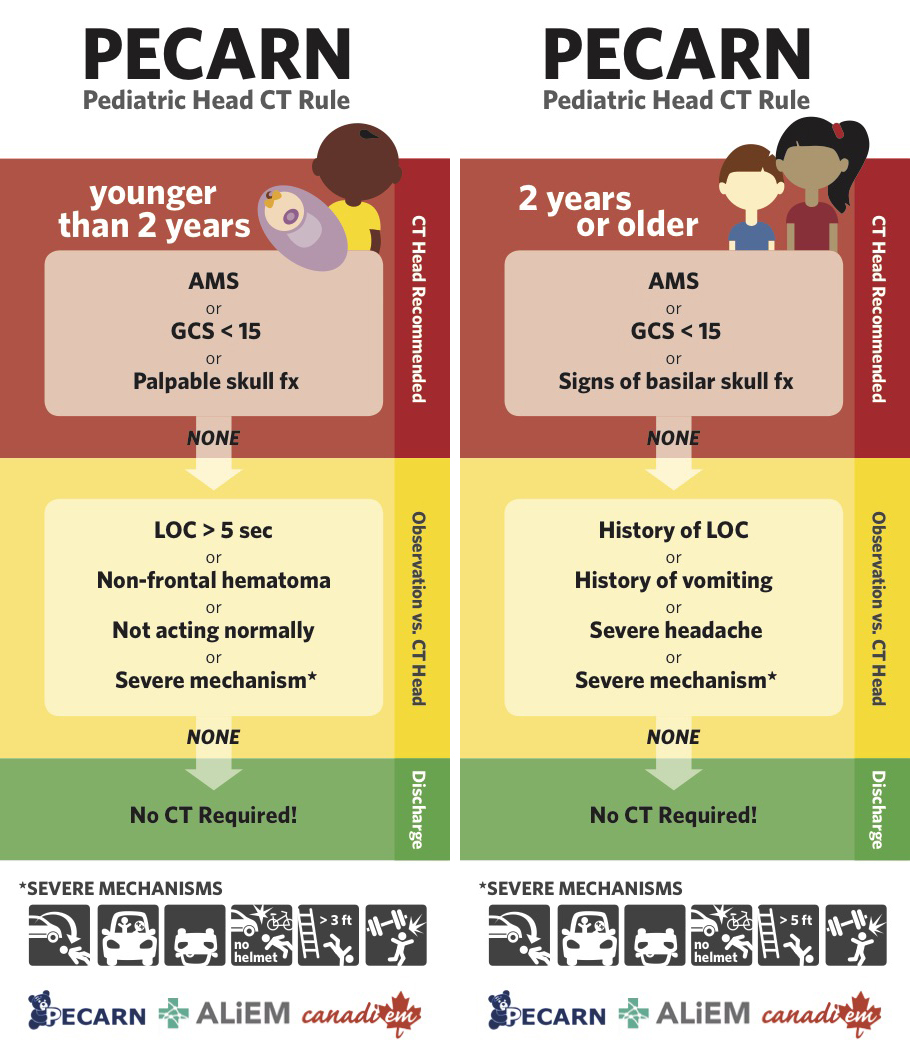

A clinical associate professor in the Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Schalick worked with a network of twenty-five pediatric emergency rooms to standardize a best practice guide for investigating the extent of the brain injury while minimizing CT scans. The study, conducted through the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, examined 45,000 children, divided into two groups — younger than 2 years old and older than 2 — to determine when to administer a CT scan.

Based on the findings, the researchers created a reference chart for pediatric emergency personnel to help determine whether to scan the youngster’s head.

The biggest change in attitude towards and resources for children with disabilities, Shalick explained, was the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935. It allocated funding and other resources to doctors, nurses, social workers and therapists to help children with disabilities.

“Disabilities are a matter of definitions and perspectives,” Shalick said.

Key facts:

- Some 600 million people around the world live with disabilities, 400 million of whom are in developing nations.

- Researchers have been seeking pharmacological alternatives that can lessen bleeding and swelling associated with traumatic brain injuries.

- Ian Roberts, a researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, tried to reduce swelling in traumatic brain injury patients by administering steroids, but after studying the effects on more than 1,000 adults, determined that they didn’t work.

- Donald Stein, a professor of emergency medicine at Emory University, discovered that pregnant mice had less trouble with traumatic brain injuries than non-pregnant mice and experimented with the hormone progesterone. The outcome of clinical trials looked promising but also resulted in negative outcomes.

- The National Institutes of Health approved a study of a synthetic molecule called tranexamic acid, which breaks down blood clots, and may have the potential to interrupt bleeding in the brain.

- According to the National Cancer Institute, the radiation in CT scans may cause cancer in children if the settings are not adjusted for their smaller body size.

- Title V of the Social Security Act was devoted to allocating new resources from the federal government to help children with disabilities.

Key quotes

- On who society blamed for a child’s disability: “Up until the middle of the 20th century, parents were often blamed for the crippled child and most frequently, as you would expect given the misogyny of our culture, it was the mom who was blamed.”

- On defining a social model of disabilities: “The social model of disability argues that even though there can be physical differences, the bigger feature here is whether somebody has or does not have a disability and that it comes from the barriers the native prejudice and exclusion that society generates itself.”

- On defining a medical model of disabilities: “The medical model argues that disability stems from some fundamental aspect of an individual, either an illness or an intrinsic disability that represents a physical condition.”

- On computed tomography scan usage: “The number of CAT scans that have been used has doubled over the decade from 1995 to 2005, but fewer than 10 percent of minor head injuries actually show trouble on CAT scans.”

Rethinking Treatment Of Traumatic Brain Injuries Among Children With Disabilities was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.