As hospital beds start to fill up across Wisconsin, people wonder where and what kind of care they’ll get if they become ill with COVID-19. Treatments have improved since the beginning of the pandemic, but doctors across the state admit they’re still learning what works and what doesn’t.

“We’re still early in this,” said Dr. Mary Beth Graham, the medical director of infection prevention and control at Froedtert and a professor of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

There’s currently no vaccine to prevent COVID-19 and one isn’t expected to be widely available until next year.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The current treatments for COVID-19 are largely experimental. Only one — the antiviral drug remdesivir — has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Understanding The Trump Treatment

Anyone can get COVID-19, including President Donald Trump. When he came down with the ailment, the president received treatment few in Wisconsin or the rest of the country have access to: an antibody cocktail called REGN-COV2.

Trump hailed it as a “cure,” though it’s still being investigated in clinical trials. The drug manufacturer, Regeneron, was quick to point that out after the president touted it as something it isn’t. Doctors also chimed in.

“I don’t see it as being a cure, but I do believe it will end up being a very good medicine though,” said Dr. William Hartman, an assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

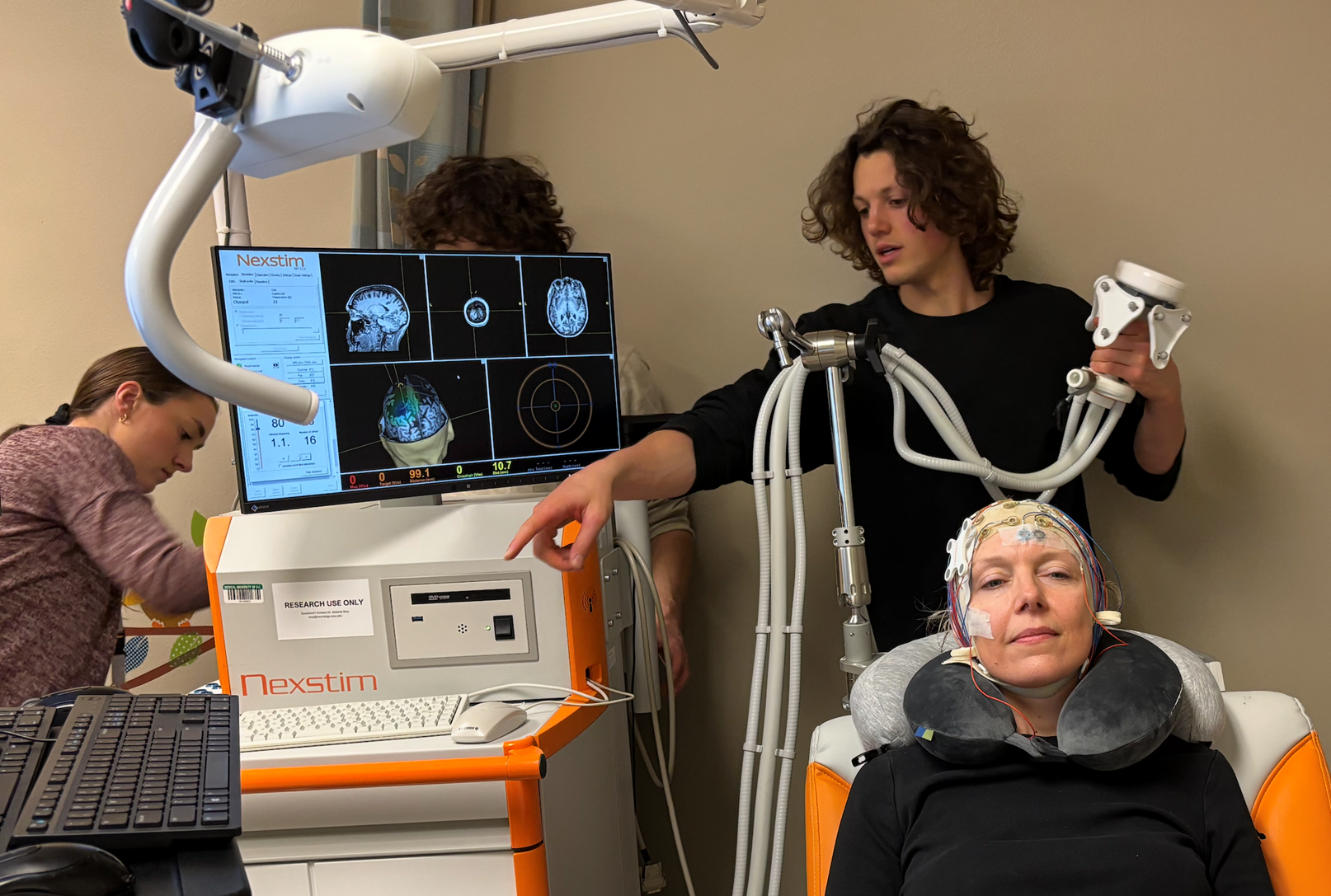

Hartman is overseeing three clinical trials for the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, including one for Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody cocktail. That’s what Trump got as part of his treatment.

But patients in clinical trials don’t know if they are getting a placebo or the medicine. That’s how researchers compare results to see if a drug works.

And that’s why the antibody made by Regeneron isn’t widely available. Scientists need to test it first for effectiveness and safety.

Patient: Decision To Enter Research Trial A ‘No-Brainer’

In mid-October, fewer than two dozen Wisconsin patients had received the antibody under the UW clinical trial.

Lane Manning, 46, was one them. He said he believes he was infected in September while in Florida for a weekend getaway, where he was visiting his mother and also helping his sister with a remodeling project. Upon returning home to Wisconsin, he didn’t feel like himself.

“I was a little fatigued, but I thought it was because I was working on the house for three days, right? Drywall, removing wall paper — it was stuff that would make you cough for a day or two. Nothing was out of the ordinary,” he said.

It wasn’t an ordinary cough, but a symptom of COVID-19. Manning and his sister had worn face masks while around their elderly mother, but not around each other. When his sister later told him that a friend who visited her Florida home had tested positive, “we kind of figured we had it, too,” said Manning. A test confirmed his suspicions, and Manning isolated himself from his family for two weeks in the basement of his Fitchburg home. Still, his 13-year-old daughter become infected. She lost her sense of smell. And even though Manning’s case was mild, he knows how devastating the disease can be.

“Yeah, I have total respect for it That’s why I’m doing the study. That’s why I’m doing this research,” said Manning, who was recognized by the Madison Area Leukemia and Lymphoma Society for his fundraising efforts this year. His father died of cancer and he said his mother, who is in her late 70s, also has cancer.

“We’ve always been big fundraisers for medical research. That’s why me jumping on this trial was a no-brainer,” said Manning in regard to the COVID-19 clinical trial.

Available treatments for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 include dexamethasone, a common steroid to control the body’s immune response to the COVID-19. They can also get the antiviral drug remdesivir and convalescent plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients.

Because of these treatments, a patient who gets COVID-19 now is likely to be better off than those who got a serious case of the disease this spring, said Dr. Hartman.

“When we started in March it really felt like we jumped out of the plane first and then decided to build a parachute. We didn’t know what was going to be effective and what wasn’t,” he said.

While treatments have improved, so has testing, according to Dr. Michael Landrum. He works at Bellin Health in Green Bay, one of the areas hit the hardest by the pandemic.

“Back in March and April, testing was constrained. So you had to be really sick and needing hospitalization before you could get a test. So we were only detecting those patients who were sickest. And so, naturally, the death rate appeared to be quite high back then,” said Landrum.

Doctors Worry As Cases Climb, Death Rate Will Rise

Currently, death rates from COVID-19 are low in Wisconsin and across the U.S., but infectious disease experts say that could change.

“This is what everybody always feared. Although the death rates aren’t currently up, with hospitalizations and ICU rates up, you can assume deaths will follow,” predicted Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine advocate and pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He spoke during a Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) livestream recently.

In Wisconsin, the death rate from COVID-19 is highest in Florence County at 3 percent. Statewide, it’s currently less than 1 percent.

But as the pandemic gets worse in Wisconsin, daily death counts are regularly breaking records. Last week, Wisconsin topped previous levels for daily case counts and deaths.

“When we see so many cases, a proportion of those are going to need to be hospitalized, and unfortunately some of those will not survive,” said Landrum.

Without a vaccine, doctors say the best way to prevent the disease is to cover your face, wash your hands and socially distance.

For those who contract the disease, some hospitals are near capacity, but doctors now have a better idea what they’re facing.

“We at least have somewhat of a playbook of how we’re approaching this illness. We still have a long way to go,” said Landrum.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.