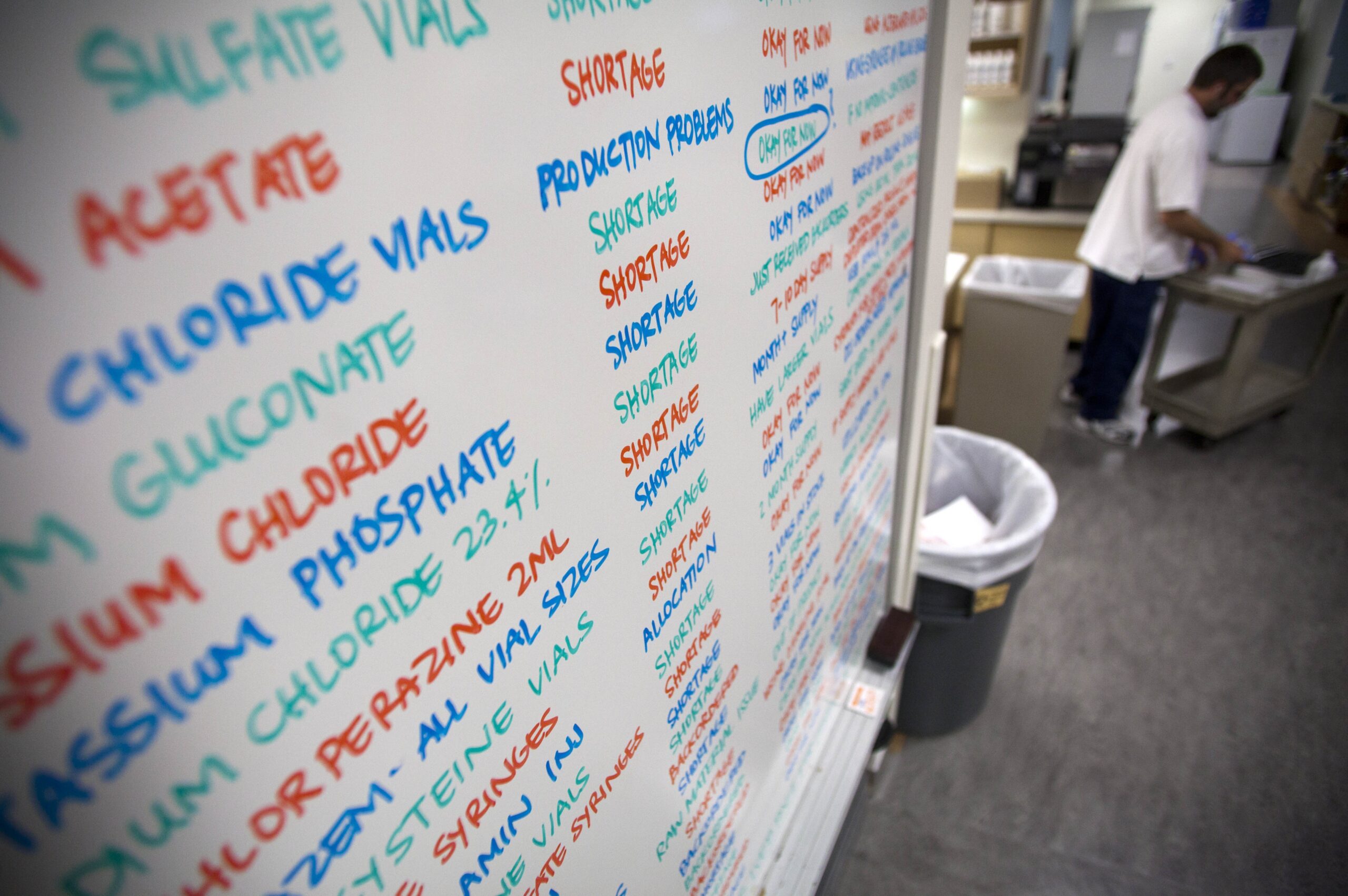

Hospitals in Wisconsin and around the country are dealing with medication shortages, forcing them to make do with what they have. And because they’re unable to get certain medications — or sometimes the most suitable drug — hospital pharmacists are having to scramble to find medications that will work out of what they have on hand.

“Once or twice a week we are short on some medication: local anesthetics, painkillers, antimicrobials. It’s not unusual to be short on a weekly basis,” said Laura Alar, director of pharmacy at Bellin Health in Green Bay.

But it’s not always possible to substitute a pill or shot for medication delivered intravenously.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“There are some antimicrobials that are only available IV (intravenously) and there are some anesthetics available IV, so route interchanges are possible but not always allowable,” said Alar.

Hospitals have also had to deal with a shortage of injectable painkillers — ironically at a time when many communities across the country are struggling with an opioid epidemic, which local hospitals are mindful of.

“If a patient for example is allergic to morphine and they’ve gone to hydromorphone and that’s not available, then the only alternative is fentanyl and based on a patient’s history, if they have abused opioids, you wouldn’t want to (use) a more potent opioid,” Alar said.

A variety of drug shortages over the last six months have hospitals across the state seeking alternatives.

“So hospitals have been struggling to keep up with things. At UW Health we’ve been able to weather it without any impact to our patients, however some hospitals around the country are running out of morphine or other drugs they’d use in their emergency department,” said Philip Trapskin, program director for medication use safety and innovation with UW Hospitals and Clinics.

Nine in 10 emergency physicians responding to a recent nationwide poll said they have experienced shortages or absences of critical medicines in their emergency departments.

Supplies become short when there are problems with the production of generic sterile injectable drugs. And not many companies do it because it’s not very profitable.

“We’re always kind of chasing our tail. One product goes short so you switch to another but by the time you’re caught up with that you have to switch to the other and vice versa,” Trapskin said.

One bit of good news: Trapskin said UW Hospital and Clinics was told this week by a vendor in Puerto Rico the hospital would no longer be limited in purchasing IV bags. Hurricane Maria damaged manufacturing facilities there last year.

Recently the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced it would form a task force to address drug shortages that peaked in 2011 and have been a persistent problem.

In June, the American Medical Association released a statement calling it a public health crisis and called for greater manufacturer transparency regarding where drugs are produced and problems that could lead to drug shortages.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.