Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic almost four years ago, millions of children around the world have gone without routine childhood immunizations.

Last year, 20.5 million children missed one or more routine vaccines, according to the World Health Organization. While better than the previous year when 24.4 million missed a vaccine, the rate remains worse than before the pandemic. About 18.4 million children missed shots in 2019.

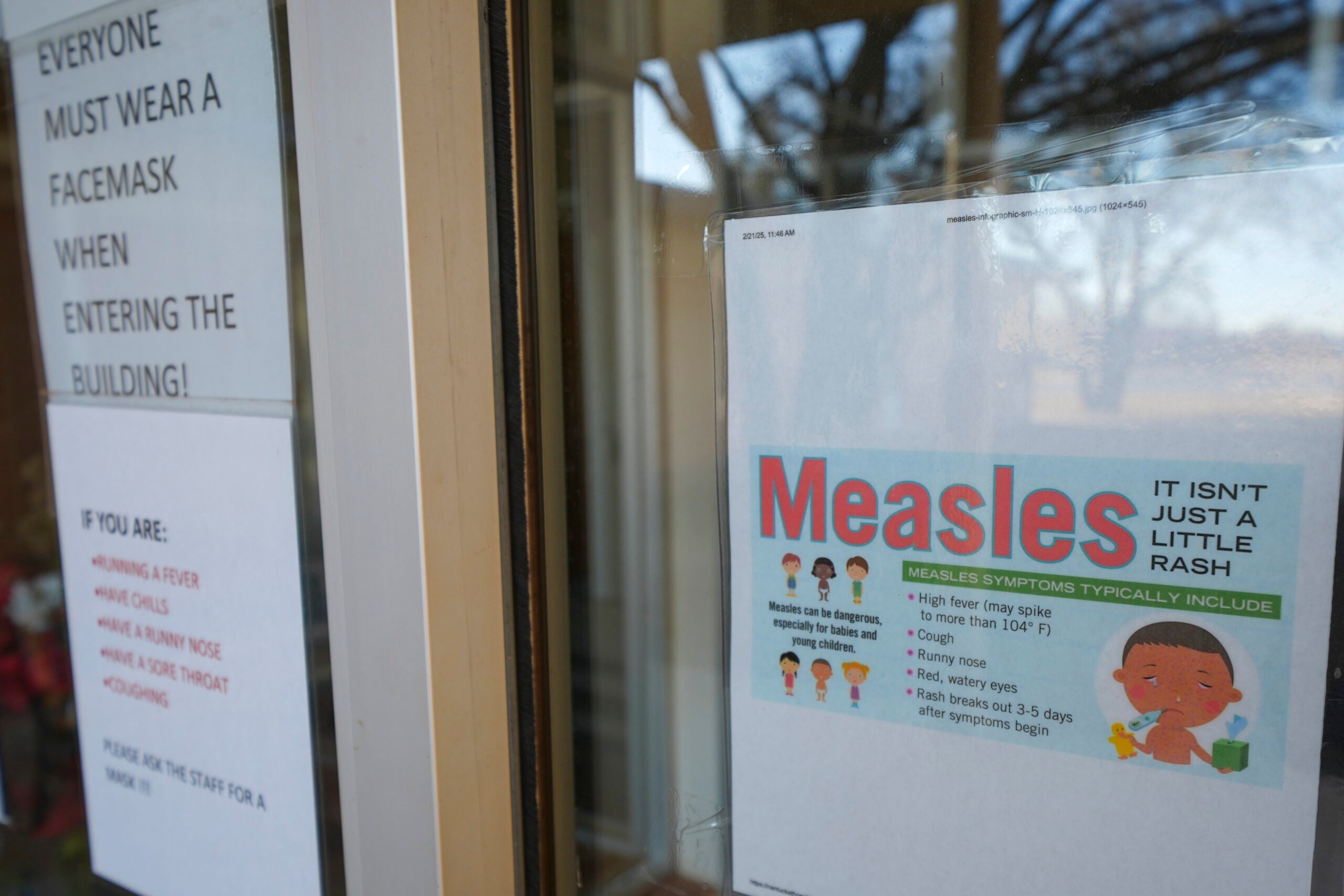

In Wisconsin, childhood vaccination rates are slightly lower than before the pandemic. In 2019, about 85 percent of children under 2 years old had at least one shot of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, according to the state health department. Last year, under 82 percent of children had the vaccine.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Statewide, immunization rates vary wildly. Last year, Manitowoc and Ozaukee counties had child immunization rates of 89 percent for measles, mumps and rubella. But Clark, Crawford and Pepin counties had rates below 65 percent. Vernon County had an immunization rate of 48 percent.

Stephanie Schauer, manager of Wisconsin’s Immunization Program, said immunization rates even more locally than the county level can affect spread of disease.

“It’s important what the rates are where you’re shopping and working and playing and going to school,” Schauer said. “We know that there can be pockets where folks are not nearly as vaccinated as we would like, and those rates can drop lower than we need to prevent disease transmission.”

Schauer and Lily Caprani, the head of global advocacy at UNICEF, recently appeared on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Morning Show” to discuss declining immunization rates in Wisconsin and around the globe and what it means for public health.

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Lily, does UNICEF approach childhood vaccination as a local community issue?

Lily Caprani: Absolutely. We know that it doesn’t matter where you live in the world. What you choose to do for your child’s health is one of the most important decisions you can make. And … it’s affected by who’s around you, what’s being said in your family, what’s being said in your friendship group, your community with other parents around you. And therefore, it’s a very, very localized issue, quite a personal and quite an emotional issue for all families when they think about their child’s health.

That means we have to really understand what’s going on when parents are deciding not to take their child to get those really important early vaccines for the young child. There’s lots of complicated reasons about why people make different decisions about that. What we want to understand is, what’s happened during the pandemic that’s changed the numbers so much?

I will say a lot of the numbers we look at around the world are improving in most countries. In the poorest countries of the world, they’re having the biggest struggle to catch up, largely because of not having the resources to do so and because those health services had so little in the way of resources in the first place.

But the U.S. and a lot of the rich countries are also facing challenges with where parents are getting their information from. And every institution and every health care worker and professional has a role in making sure that we tackle this issue now.

KAK: Stephanie, I’m wondering, as we talk about trust, is vaccine hesitancy a piece of this?

Stephanie Schauer: Yeah, it certainly is. There’s two pieces that affect vaccination rate. One is that willingness or the desire to be vaccinated. We know that parents have questions, and rightly so. The problem is not having questions. It’s really making sure that they’re getting the answers that they need.

We trust our health care providers regarding the health of our children. We take them there for regular checkups, and it’s important that we ask them the questions that we have about vaccines so that we feel comfortable making the decisions to protect our children.

For example, there’s lots of misunderstanding about how vaccines work and how long they stay in the body. They’re really a way of teaching your body to recognize a particular virus or bacteria and allow your immune system to build up. Having folks understand how vaccines work and what they do and don’t do is key.

The other piece is that we are very fortunate here in the U.S. and in Wisconsin to have the Vaccines for Children program. This is a federal program that covers children who are uninsured. And they can access the vaccines free of charge. It’s a network of 720 locations throughout the state, including health care providers and local and tribal health departments. And nearly every place that serves children for primary care is part of this program, and they screen every child to see if they’re eligible.

We really want to make sure that once a parent has gotten the information and made the decision to have their child vaccinated, that cost isn’t a barrier.

KAK: Lily, if a disease — measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria — is not present in families’ lives, in their community, there is that question: Do I still need to vaccinate my child?

LC: Maybe we don’t see the risk of these illnesses because they just haven’t been a common part of everyday life in the richer world. We’re starting to see a few of these measles outbreaks where it’s just remarkable how quickly they can spread when a community isn’t vaccinated.

If you live in a pocket of a community or a neighborhood where the majority has not had a measles vaccine, you will see that spread around like wildfire. It’s one of the most infectious illnesses. And it can really damage children. If they don’t die from measles, they can certainly suffer from long after effects from the illness. But we don’t see it as often and therefore, perhaps we don’t see the root cause.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.