The move to keep older people in their own homes as long as possible has meant more demand for home health care workers — a job that is not only tough, but that can be low-paying as well.

Home health care workers go into an older or disabled person’s home to help them with tasks that range from the mundane, like shoe-tying, to the intimate, like baths and going to the toilet.

It’s work that Shelly Waltman enjoys.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“It’s not like a job over there,” said Waltman. “It’s just like having another family out there.”

Waltman is a certified home health provider who works through N.E.W. Curative, a nonprofit based in Green Bay. Four mornings each week, she works with a couple who are in their 70s.

“Right now I wouldn’t call them ‘elderly,’ but aging,” she said.

The husband has Alzheimer’s disease. She gets him cleaned and dressed and monitors his medication.

Waltman has done the work for years and said it takes patience and compassion.

“One minute, like a lamb — the next minute, you could be getting hit,” she said. “So, you’ve got to be able to take the tough with the good.”

Caregivers like Waltman might be hired by family members who need a break, or they could be the client’s main source of help. They can work through private companies, or places like N.E.W. Curative.

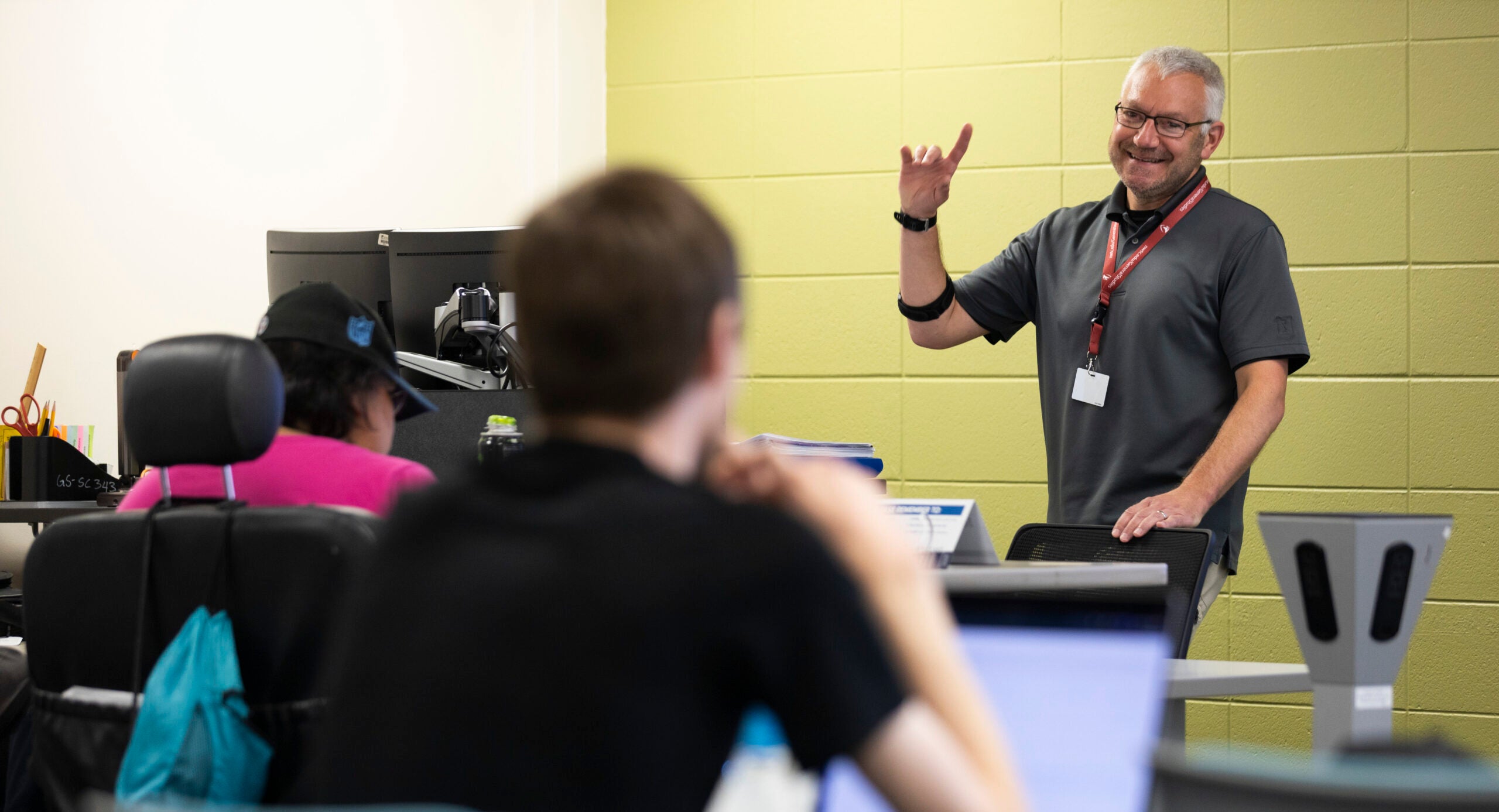

All in-home caregivers need some level of certification. Green Bay’s Northeast Wisconsin Technical College graduates 700 certified nursing assistants each year. Students can also get a short personal care worker certification.

Cindy Theys, the school’s associate dean in the health sciences department, said the work is rewarding, but nursing assistants deal with people when they’re not at their best.

“You can’t curl up your nose if something doesn’t smell pretty, because that’s what is going to happen,” said Theys. “Even the ability to touch other people — there are people who are very uncomfortable being touched, and there’s people who are very uncomfortable touching others. But you will have to be touching people.”

NWTC claims an 85 to 90 percent placement rate for its health care graduates. Starting jobs pay between $10 to $12 an hour.

Those numbers sound good to Erica Huettl, who is pursuing a registered nursing degree. She is looking to get experience dealing with patients and is considering a job as a nursing assistant in either an in-home setting or at a nursing home. She said there’s a lot to choose from, and it’s a good way to get experience — but not to get rich.

“Obviously, with more education and the higher you go with nursing, that pay goes up,” she said.

Using a CNA as a launching pad can pay off over time. A recent NWTC survey of its graduates shows RNs can make about $50,000 dollars a year within five years of graduation.

For those who aren’t pursuing a higher degree of nursing, home health care seems to be more of a lifestyle than a career. Shelly Waltman said it’s easy to get attached to clients, even those who are rather difficult.

“Watching somebody fail; knowing that some types of the things they’re going through will progress,” she said. “(Knowing) how hard of a time the family has with it and being able to empathize. Because I did have a grandma who had issues like that. That’s the hard part.”

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a six-part series on aging and elder care in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.