2020 has left us all with plenty to be angry about — lost jobs, stress over the election, feeling stuck, grief or isolation during the pandemic, to name a few.

As uncomfortable of a feeling as anger can be, it isn’t necessarily bad and shouldn’t be dismissed, particularly if it can inspire action or change, said Ryan Martin, a professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and co-host of the podcast, “All the Rage.”

The key is learning to manage and control the negative effects of the emotion.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“I like to think about anger from an evolutionary perspective,” Martin said. “It served our ancestors … in this really valuable way. It alerted them to unfairness or injustice, and then it actually energized them to confront that injustice.”

“When our fight or flight system kicks off, which is what happens when we become angry … if we can think of that as fuel, we can harness that fuel and use it in positive and pro-social ways. We don’t have to swing a club, we don’t have to be aggressive,” he continued.

To help rethink anger and overcome the harmful side effects, Martin shared advice on how to better manage it with WPR’s “Central Time” host Rob Ferrett.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rob Ferrett: 2020 has thrown a lot at us. Are we angrier now than we have been before?

Ryan Martin: I wish we had a good, solid answer to that question. I think there’s reason to believe we are right now.

The pandemic is a great example of this; it’s leading to this underlying level of stress for, I think, ultimately everyone. Some people are going to be more anxious than others. Some people are experiencing more negativity than others. But the job loss, the financial challenges, being trapped at home, all of those things are leading to this sort of underlying sense of discomfort that makes you more on edge and is likely to lead to increased episodes of anger.

RF: How do we practice dealing with anger better, so we’re ready for it when it comes along?

RM: I think the first step is being able to recognize it in yourself and think through what it means. One of the first things I encourage people to do is ask themselves, “Why am I angry?” And sometimes that answer is really obvious, “I’m angry because ‘X’ happened.”

The next thing to do is to find a way to stop and take a little break. Whether that’s deep breathing, counting to five or 10 — whatever it takes to get yourself to a place where you’re thinking a little more clearly about what you want to do or what the goals are.

Then start thinking about how to solve whatever the problem is that led to the anger in the first place. How can I direct this anger to fix it?

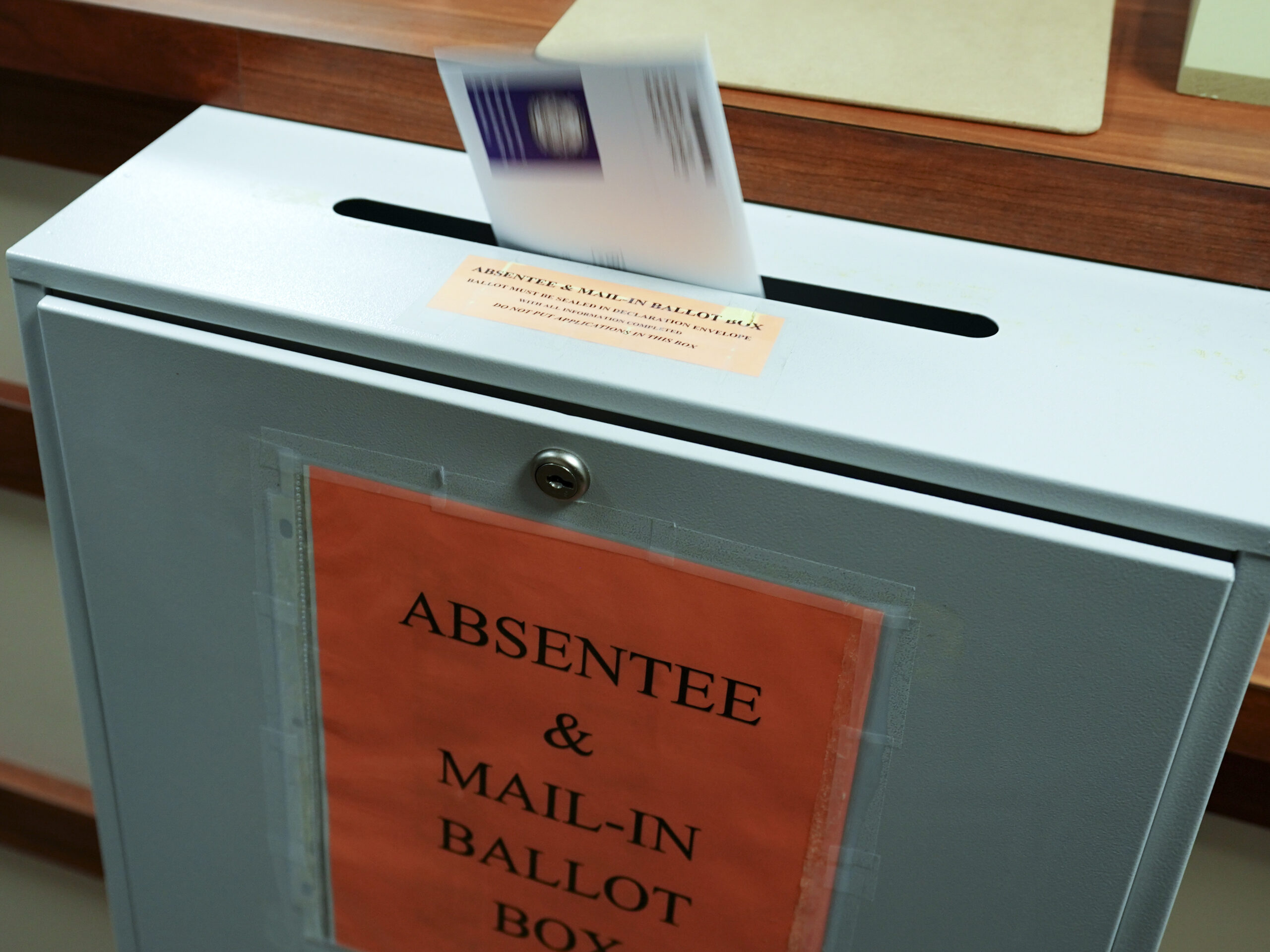

RF: How do we translate underlying anger that can feel out of our control into action? For example, if we’re frequently upset by politics or the news, how do we use it to do something constructive now or in the future?

RM: This is what people commonly refer to as outrage fatigue. You know, I’m just outraged all the time over politics. I keep getting mad. And so I’m now at a point where I’ve just turned off the news, I want to bury my head in the sand a little bit.

It’s OK to want to not feel angry all the time and to turn that off sometimes. But it’s also worth noting that there is some value in staying mad if my anger can be the fuel that gets me to run for office, the fuel that gets me to go out and protest or write letters to the editor. Having a healthy emotional life is about being able to sort of bring that anger up when I need it, and not just decide it’s in my best interest not to feel this way, so I’m going to push it away.

RF: Looking at the road rage moment — when somebody cuts us off and then honks at us — how, in that quick moment of anger, can we dial down that instant response?

RM: This is probably the hardest and takes the most practice. We respond quickly, and we respond in the ways that we sort of grew up responding. Try to think about it ahead of time and reflect on some of those situations after the fact, asking yourself, “Am I glad that I did this? If my gut instinct was to give someone the finger, or honk back or whatever, am I glad that I did that? What could I have done instead?”

Reflecting a bit on some of those situations, thinking through what you wish you would have done that would have been more productive and more adaptive can go a long way to shaping how you’re going to respond the next time that happens.

RF: One approach is the idea that we can’t just bottle up our anger, we have to express it in some way, like by punching a pillow. Does that actually work?

RM: No, it does the opposite. It’s actually really bad for you. It’s so bad for you that we have a whole area of study referred to as the catharsis myth in psychology, which essentially has identified that those approaches exacerbate anger problems.

I had a soccer coach once who used to say, “Instead of practice makes perfect, practice makes permanent.” And he said if you practice things incorrectly, then you will do them incorrectly. And I think some of what’s going on when we punch pillows and when we break stuff is we’re practicing our anger incorrectly. And it makes us more likely to do those things later on when we’re in another interaction.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.