Republican lawmakers on the Wisconsin Senate’s natural resources committee have approved changes to a bill that would create grants for local governments to address PFAS pollution, but Democrats opposed provisions that limit regulators’ authority to address the chemicals.

The committee voted 3-2 in favor of the plan Wednesday, with all Republican lawmakers supporting the changes and all Democrats voting against. The legislation is sponsored by State Sens. Eric Wimberger and Rob Cowles — both Republicans from Green Bay. Reps. Jeff Mursau, R-Crivitz, and Rob Swearingen, R-Rhinelander, are sponsoring the bill in the state Assembly.

The vote clears the way for the full Senate to vote on the bill before it would be sent to the Assembly, although a spokesperson for the governor hinted that the plan is likely headed for a veto.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The plan sets the framework for doling out $125 million for PFAS mitigation included under the current two-year state budget by the Legislature’s budget-writing committee and Gov. Tony Evers.

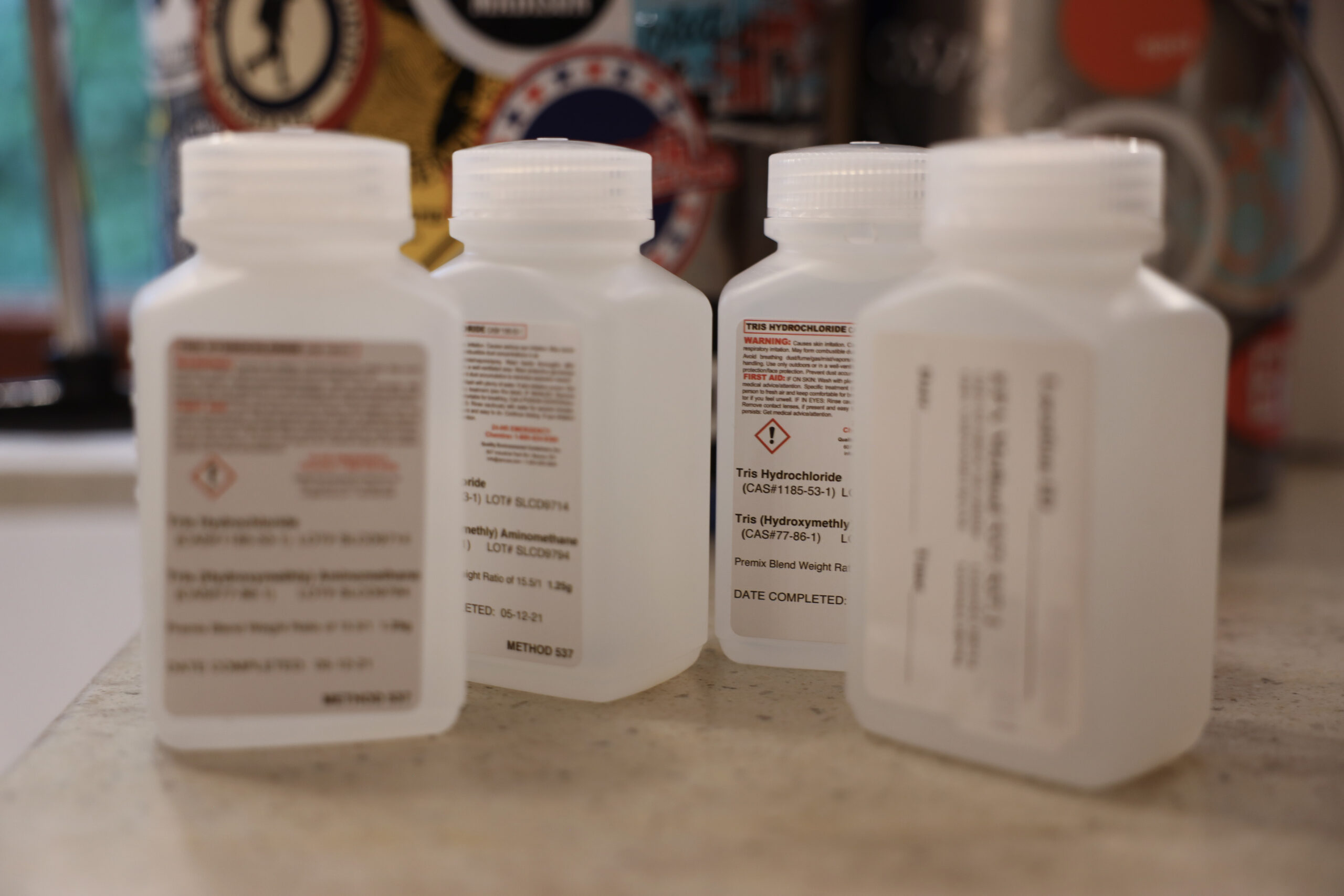

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals used in cookware, food wrappers and firefighting foam. The chemicals don’t break down easily in the environment. Research shows high exposure to PFAS has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines over time.

GOP legislators who sponsored the bill said during a press conference that the bill provides grants to municipalities and landfills, and it limits the state Department of Natural Resources’ power to order innocent landowners to clean up the chemicals.

“This bill is directed at getting all people clean drinking water and helping innocent landowners,” Wimberger said. “It accomplishes that.”

Wimberger and Swearingen said landowners and farmers are reluctant to test for PFAS and report results for fear of being financially destroyed.

Under the bill, the DNR wouldn’t be able to require a property owner to test for PFAS under the state’s spills law unless it had probable cause to believe PFAS levels would likely exceed state or federal standards. The Environmental Protection Agency has proposed drinking water limits of 4 parts per trillion for the two most widely studied PFAS chemicals, which is 17 times lower than the state’s current drinking water standard of 70 parts per trillion.

The DNR also wouldn’t be able to prevent or delay projects based on the presence of PFAS contamination unless there’s substantial risk to the environment and public health. The bill also allows exceptions in cases of negligence or requirements under the federal Clean Water Act.

Committee member Diane Hesselbein, D-Middleton, voted against the legislation even though she said there are many good parts of the bill that support municipalities and private well owners in addressing the chemicals.

“I cannot support legislation that limits the authority of the DNR to combat PFAS contamination around the state,” Hesselbein said in a statement after the vote. “Prohibiting the DNR from requiring action to address PFAS contamination unless PFAS levels exceed promulgated standards does not help when there are no promulgated groundwater standards.”

Groundwater standards for private wells are currently lacking, although the DNR is crafting limits for the chemicals. Around a third of state residents get their drinking water from private wells.

Prior to the vote, Cowles said the bill represented a “solid compromise” that didn’t give every group what they wanted, but met many needs. He noted the bill attempts to advance research to address PFAS, which would include a study on the cost and effectiveness of different methods to treat the chemicals.

“PFAS has been a tremendous concern for our communities throughout the state,” Cowles said. “We’ve seen more and more sites that these contaminants have been popping up on a regular basis, and it’s possible there’s more sites that we don’t know about.”

A spokesperson for Gov. Tony Evers said the vote was disappointing after working for months to reach consensus on the proposal.

“It’s unfortunately not surprising Republicans still don’t share our commitment to finding real, meaningful solutions to the pressing water quality issues facing our state,” said Evers spokesperson Britt Cudaback.

The bill would create a municipal PFAS grant program that would provide money for testing of public water supplies and wastewater treatment plants for the chemicals. The bill also includes an innocent landowner grant program that aims to provide aid to people unaware of PFAS pollution on their properties.

Opponents worry changes are too easy on corporations

Under the plan, the DNR could not take enforcement action against anyone that voluntarily lets the agency clean up their land at the department’s expense. The Legislature’s powerful Joint Committee on Finance would also be able to approve grants for any person the Wisconsin DNR deems eligible as an innocent landowner.

Some opponents of the changes, including the River Alliance of Wisconsin, say lawmakers made it easier to let corporations off the hook for PFAS pollution.

“The language could give too much power to the legislature and DNR leadership to broadly allow corporations to qualify as ‘innocent’ landowners who are eligible for clean up funding and let them off the hook for responsibility for clean-ups,” said Bill Davis, the group’s senior legal analyst, in a statement. “Changes would take resources away from individual landowners, homeowners, and families.”

The environmental advocacy group Clean Wisconsin said in a statement it’s disappointed the changes didn’t address concerns about limits on the DNR’s authority to test for, and clean up, the chemicals. The group also called on the Legislature to pass the municipal grant program as a standalone bill separate from the innocent landowner grant program.

“I think this is a little bit out of balance with regard to that because there are potentially going to be folks who are not going to be made need to chip in for cleaning up some of this pollution when we know that they were part of the problem,” said Evan Feinauer, a staff attorney for the group.

Wimberger said concerns over limiting DNR authority were “overblown.” He said the bill doesn’t have any implications for what’s going to happen to industry or manufacturing.

A coalition of business groups that includes Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, the Wisconsin Paper Council and the Midwest Food Products Association also opposed changes to the bill. The groups said they want to protect Wisconsin businesses from “overzealous regulators” and supported the creation of an innocent landowner grant program.

“Accordingly, we have sought clear program guidelines to ensure that businesses with property contaminated with PFAS through no fault of their own are eligible for the proposed program. (The latest amendment to the bill) fails to meet both of these reasonable goals,” the coalition wrote in comments to the committee.

Communities across the state, including Peshtigo, Marinette, Campbell, Wausau, Eau Claire and Madison, are facing PFAS contamination in public and private wells.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.