One of the true pleasures of my job is that I sometimes get to pick books simply because I love them. One of the great perils of my job is that I sometimes get to pick books simply because I love them.

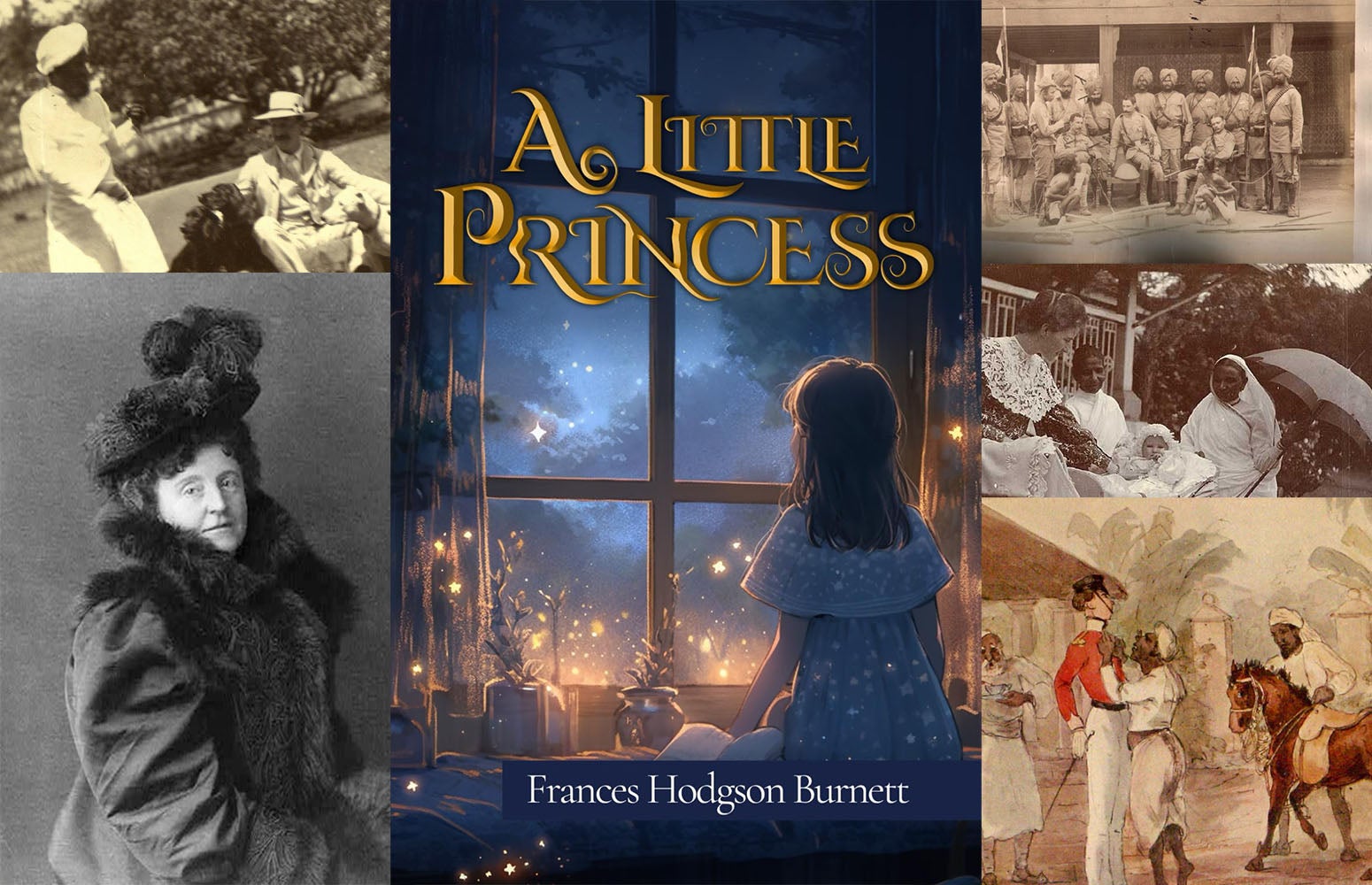

Case in point: “A Little Princess,” written by Francis Hodgson Burnett, currently airing through Dec. 29 on WPR’s “Chapter A Day.”

I love the movie and have wanted to air the book on the program for quite some time. It has a lovely message — especially for the holiday season — of kindness, generosity, and being positive in the face of adversity. It teaches lessons about perseverance and self-belief.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That said, I always hesitate because reading it through a modern lens starts to reveal how many potential “landmines” there are in this little book I love so much.

Poor little rich girl

The first lies in the fact that “A Little Princess” is basically a book about privilege. A little girl who lives a privileged life, loses that life and then regains it.

“Honestly, do we really need be hearing books about privilege… now… with everything that’s happening in the world?” I hear you say. But Sara’s story is a lesson in privilege used for good.

She shares her toys, treats, dolls with all the other students and even the servants. When she loses said privilege, that benevolent spirit remains. She wants to “spread largess” even though she has nothing to offer her friends except her kindness and imagination.

One potential landmine defused.

The Raj

Then we run headlong into an entire minefield — namely, the British Empire. Let’s face it, “A Little Princess” is peppered throughout with Orientalism, particularly in descriptions of Ram Dass — his “dark” face, “black” head, his ability to scamper over rooftops, and his “magic.”

The “Indian Gentleman” (who may or not be truly Indian) is imagined to be a “heathen.” Not to mention the use of specific and offensive Indian words.

I needed to talk to an expert. Enter Mou Banerjee, assistant professor of history with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

“Chapter a Day” host Bruce Bradley and I sat down with Banerjee to discuss how to navigate this minefield. You’ll find links to our discussions down below.

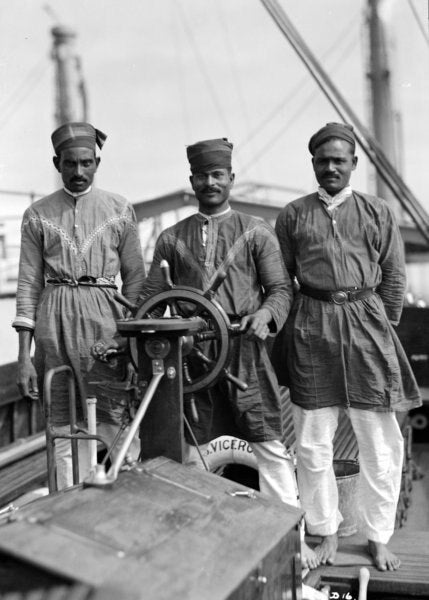

Banerjee gave us some context to a couple of potentially troubling words: Lascar and Sahib. Lascar has a long and varied etymology beginning as an Arabic word meaning army. But in the 18th and 19th centuries with the coming of the seafaring British, the term referred specifically to “sea men from particular parts of India, including what is now Bangladesh in an area called Chittagong,” Banerjee said.

She explained, “We find that reference in ‘Wuthering Heights’ as well, when a little wild child is brought and it’s a Lascar child. So, obviously it’s a Bengali child who’s been on a ship and is now adopted. Heathcliff is Bengali which has always given me some sort of shiver.”

Banerjee continued, explaining Lascar is “no longer in the common parlance but has remained in memory. Chittagong is now Asia’s largest shipbreaking yard but it’s also the world’s largest Rohingya refugee camp. So certain kinds of connotations around those words keep remaining.”

The word Sahib, according to Banerjee, “has a very, very complex origin … in Arabic it is someone who is a friend, and someone who is a friend of the Prophet.”

In the 17th and early 18th centuries in India, “Sahib” was used as a sign of respect for anyone of higher standing. But, Banerjee continued, “by the time it’s the mid-18th century, at least in Bengal where the British Empire actually begins, it has come to mean very specifically a white man in a position of authority.”

Since the fall of the British Raj, “it has entered the lexicon,” Banerjee added. “Anyone in a position of power, of authority is a Sahib. The Burra Sahib is someone who is the boss.”

The Jewel in the Crown

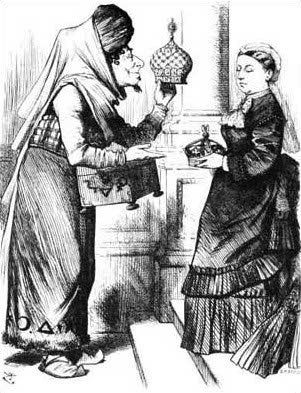

Another landmine is Burnett’s perceived use of Orientalism. Banerjee said we need to understand England at the turn of the 20th century.

When Francis Hodgson Burnett — the author of “A Little Princess” — put pen to paper in 1905, Britain controlled nearly 25 percent of the world’s land mass and population. The British Raj had succeeded in subjugating the Indian populace, while romanticizing the process for the “folks back home” by calling their newly conquered land “The Jewel in the Crown.”

In order to conquer groups of people, Banerjee said, those groups need to be dehumanized — which in this case was done by making them mystical. Newspapers, popular fiction, Evangelical Christian missionaries and returning soldiers depicted the subcontinent as a world of strange people with magical powers and odd customs.

We know that Burnett fell under the lure of this propaganda because although she’d never visited India, her books are filled with the romantic, mystical imagery of the time. Many of those popular depictions are influenced by, as Banerjee put it, the “colonial fear of the unknown”.

This is the wonderful thing about literature. If you actually read something as moving as ‘A Little Princess,’ it opens up a very, very interesting world for you. A world that we still hear haunting echoes of in the modern day.

Mou Banerjee, assistant professor of history at UW-Madison

Banerjee said because of the attitudes of the British toward the subcontinent and its peoples at the time “A Little Princess” was written, landmines cannot be avoided or explained away, but should be discussed.

“This is the wonderful thing about literature,” she said. “If you actually read something as moving as ‘A Little Princess,’ it opens up a very, very interesting world for you. A world that we still hear haunting echoes of in the modern day.”

By the way, Banerjee is also well-versed in 19th- and 20th-century English literature and was delighted to compare and contrast those authors and their use of Indian imagery in their works. A snippet of our discussion is included at the end of Chapter 1. But I urge you to listen both the original 17-minute discussion, as well as the follow-up discussion about the intertwining of religion and colonialism. It is a mini masterclass in the British Raj and 19th-century British literature.