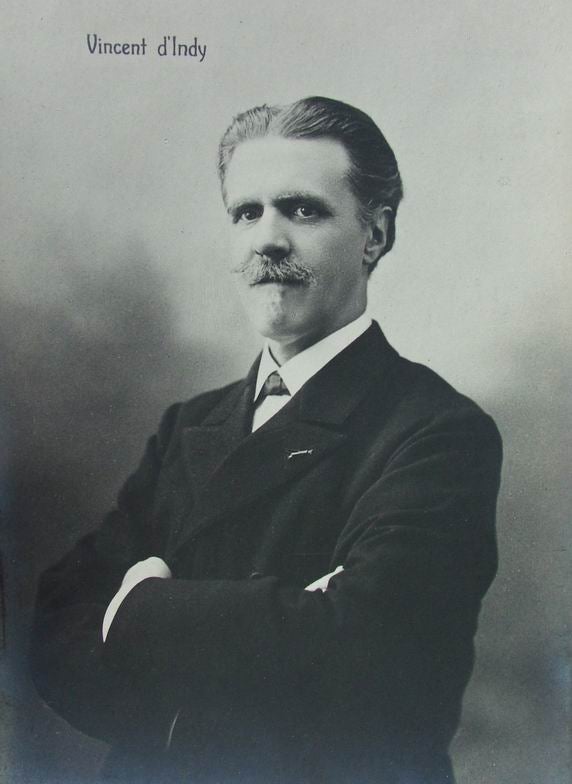

How direct should an established composer be when appraising the work of an up-and-comer? Vincent d’Indy would’ve had two answers to the question — one before and one after getting advice from Cesar Franck. D’Indy recalled:

“Once I had played a movement of my string quartet for him — which I naively thought would win his approval — he was silent for a moment. Then, turning toward me with a mournful look, he said something that I’ve never been able to forget because it’s had a decisive influence upon my life.

“He said, ‘there are some good things in it. It shows spirit and a kind of instinct for dialogue between the parts. The ideas wouldn’t be bad — but that’s not enough. The work isn’t finished.’ Then Franck added, “in fact, you really know nothing whatsoever.’

“Seeing that I was shocked and horrified by his opinion, Franck went into some specifics and concluded, ‘Come and see me if you want to work together. I could teach you composition.’

“The visit had taken place very late in the evening. When I got home, I lay awake, balking at the severity of his opinions. I told myself that Franck was an old-fashioned musician who knew nothing of youthful and progressive art. And yet, in the morning, after I had calmed down, I picked up my poor quartet and went over the master’s criticisms one by one as he had scrawled them on the manuscript. And I had to admit to myself that he was completely correct. I knew nothing.

“I went to him, a bundle of nerves, and asked if he would be good enough to take me on as a student, and he let me into the organ class at the conservatory, of which he had just been appointed professor.”

Vincent d’Indy, soon to become a major French composer in his own right, describing his first encounter with a blunt but effective teacher, Cesar Franck.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.