Environmental and climate activists are calling on the U.S. Forest Service to halt logging of mature and old-growth trees that are crucial for storing carbon to combat climate change, including a project in northern Wisconsin.

The Fourmile Vegetation Management Project in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest is cited among the 10 worst logging projects on federal lands, according to a report released by a coalition of groups this summer. The project 7 miles east of Eagle River would log nearly 12,000 acres in parts of Oneida, Vilas and Forest counties. It’s expected to yield around 45 million board feet of timber.

President Joe Biden issued an executive order on Earth Day that directed federal officials to inventory older forests on federal lands. They’ll then have to coordinate strategies to reduce wildfire risks, analyze threats and develop climate-smart policies.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Environmental and climate advocates fear older trees will be lost to logging before that work is done, according to Andy Olsen, a senior policy advocate with the Environmental Law and Policy Center or ELPC.

“At ELPC, we are calling on the Forest Service to freeze all logging of mature and old-growth trees while this process goes forward, and especially in the Fourmile project area,” Olsen said.

Olsen said more than half of timber stands set to be logged are 80 years and older.

Wisconsin has nearly 17 million acres of forest land and roughly 1.5 million acres in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest. State data shows old-growth forests that are 120 years or older account for a little more than 1 percent of timberland.

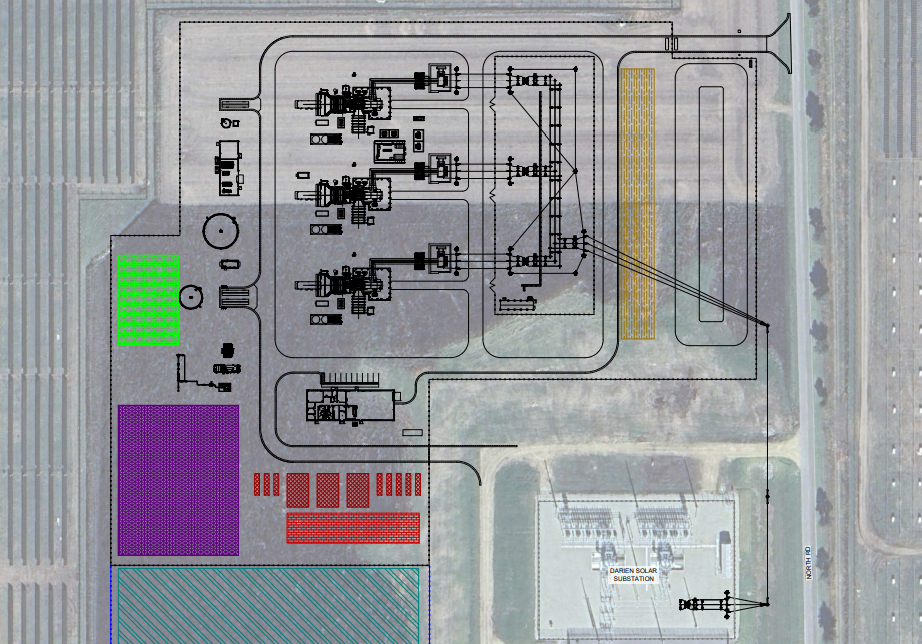

A map of the Fourmile project in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest. Courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

In an environmental assessment, the U.S. Forest Service said the Fourmile project would help meet demand for wood products, increase public safety related to wildfire risks and enhance recreation. The review said the area proposed for logging has an overabundance of older trees, saying too many could lead to reduced resilience to insects and disease or a decline in certain species.

Last year, multiple environmental groups, including ELPC and Clean Wisconsin, wrote a letter to the U.S. Forest Service asking the agency to suspend the project and conduct further review. They said the Fourmile plan was developed after the Trump administration issued an executive order to accelerate logging on federal lands with limited environmental analysis.

The groups argued the agency failed to fully address climate change in its review. The U.S. Forest Service said plans to log the area wouldn’t increase greenhouse gas emissions without any project-specific analysis, noting a full examination of efforts to mitigate emissions would be complex and broad. The agency issued a finding of no significant impact related to the project in late 2020.

Environmentalists say the U.S. Forest Service should reconsider its decision by examining the best available science to consider climate change, habitat and public health effects through a full environmental impact statement. Olsen said the project area includes sensitive species like the federally endangered northern long-eared bat and state-endangered American marten, which is a rare weasel-like species that thrives in old-growth forests.

“In terms of biodiversity, protecting the mature and old growth stands also maximizes biodiversity at a time when we’re facing an extinction crisis, globally and in North America as well,” Olsen said.

The project’s environmental assessment found logging in the area would immediately reduce suitable habitat for the American marten by 19 percent, which is expected to improve but not return to its current state within five years.

The U.S. Forest Service rejected concerns of environmental groups in a Jan. 20 letter this year, saying the project follows a 2004 plan that balances various uses of the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest.

“The Fourmile Vegetation Management Project will promote the long-term health and productivity in the Project area, and in tum its potential to continue sequestering carbon at current rates,” wrote U.S. Forest Service Chief Randy Moore.

A U.S. Forest Service study in 2014 found the rate of carbon sequestration is declining in northern Wisconsin forests despite an increase in carbon stocks in the previous decade. Since 2000, northern Wisconsin forests and wood products stored around 1.5 million metric tons of carbon per year.

Researchers concluded the level of carbon sequestration along with intensive logging for wood products could be sustained “unless climate change or natural disturbances increase significantly.” Olsen noted the same study said there’s potential to increase carbon stocks by allowing more trees to mature. Yet, researchers said any increase, though substantial, would be limited over the long term.

Wisconsin’s Green Fire also recommended changes to the project, but the conservation group found the U.S. Forest Service followed standards and guidelines set forth in its 2004 plan. Critics have said that plan is vastly outdated. Ron Eckstein, the group’s co-chair of its forestry work group, said they had concerns about management of roughly 1,600 acres of trees that dated back more than a century.

“We are recommending that they apply certain standards and guidelines that are currently in the forest plan very carefully to some of the older stands, so that they’re not compromised and that they continue to develop and maintain old-growth characteristics,” said Eckstein.

Eckstein said they recommended smaller timber stands of 10 acres or less of white pine, red pine and hemlock be left alone, highlighting the difficulty of regenerating hemlock trees.

Related to climate change, he said the biggest thing managers can do is keep forests intact rather than converting them for agriculture or development, as well as extend their range. Eckstein added the agency’s plan for managing the forest meets climate change objectives.

“The way they developed the forest plan to be (a) fairly diverse forest with all different kinds of age classes, that is in line with how we should manage forests through the lens of climate,” said Eckstein.

A U.S. Forest Service spokesperson said in an email that current land management plans include conservation of old-growth timber stands.

“We use the best available science, rigorous environmental analysis, and extensive public engagement to guide our decision-making,” wrote E. Wade Muehlhof, a spokesperson for the agency.

Moving forward, the agency said it recognizes the value of mature forests and their benefits to biodiversity, carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat, water quality and recreation. The U.S. Forest Service acknowledged they’re threatened by climate stressors and may require interventions to reduce risks, including wildfire, as it works to inventory old-growth trees.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.