Kenneth Farmer spent a lot of time in the courtroom as a public defender and prosecutor.

But Farmer’s first experience with a jury trial took place when he was just 19 years old, when he served as a witness at his brother’s commitment proceeding.

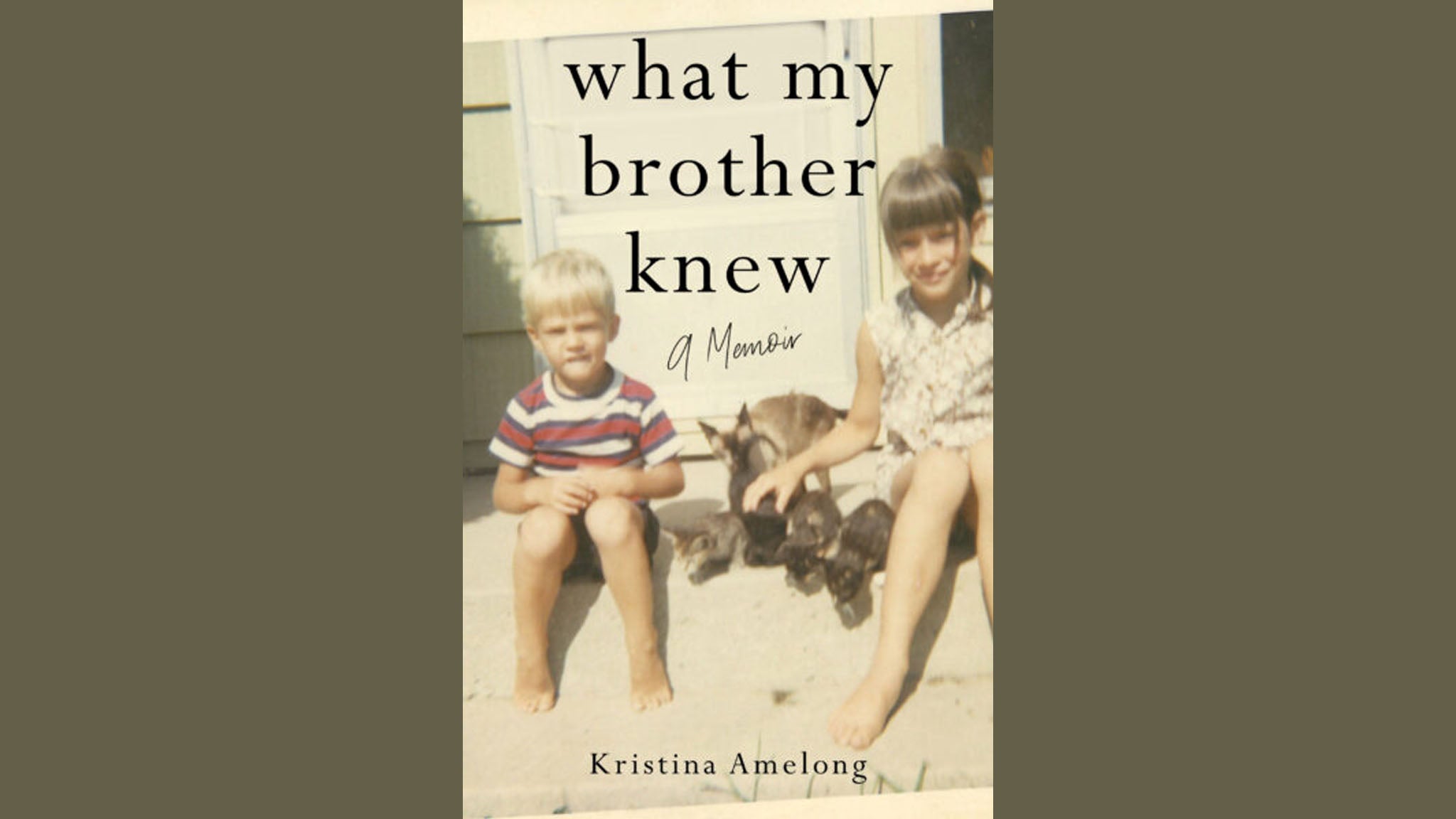

His brother suffered from paranoid schizophrenia. Farmer’s recent book — titled “Lee,” after his brother — chronicles his brother’s spiral into the serious mental health disorder that affects a person’s ability to think and act clearly.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

People who have schizophrenia may struggle with telling the difference between what’s real and what isn’t. Some may be prone to violent outbursts like Lee, who was eventually committed after assaulting his mother and others.

Lee has since died of lung cancer.

Farmer, who is from Stevens Point, joined host Shereen Siewert on “Route 51” to discuss his experience over four years writing “Lee,” and his own coming to grips with how his family coped with the diagnosis.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Shereen Siewert: Ken, this is not your first book. It’s not even your second book. In the preface to “Lee,” you say it was very difficult for you to make this decision to even write this. So what left you feeling so conflicted, and what persuaded you to finally put this into words?

Ken Farmer: Well, my mother was against committing my brother until the day she died. And I think that I felt like if I wrote the book, I would be exposing my family. And to a certain extent, there was a stigma that I was still feeling over that, not only because of my mother, but in general the embarrassment about what had happened to our family. And I thought that, boy, you know, maybe someday I’ll see my mother again. I don’t know if there’s an afterlife, but if I saw her, I would be condemned by her for having come forward about this.

SS: You said in your book that your mother had had this feeling that committing him would “ruin him.” How prevalent are those kinds of feelings, do you think, with other families who are dealing with this very same thing, that feelings of shame, the feelings of embarrassment?

KF: Well, it’s something that occurs just about in every family that deals with this. There are certain patterns of dysfunction that families engage in when it comes to this disease that are pretty patterned things.

One of the things that occurs is anger, perhaps by some family members that the person that has the disease is taking all up the money and not the attention that they should have. I had that pattern.

Another pattern is where somebody tries to compensate and be the family hero, like you would find in any dysfunctional family.

But one of the major things is stigma. It’s the embarrassment about it. And I can’t say that I’m proud of the way I dealt with my brother at times because of that stigma. I was so embarrassed about the way he was. I mean, literally, there were times where I would walk on the other side of the street rather than talk to him if I saw him in public.

SS: Lee was your only sibling. He was your older brother. And you’ve mentioned that your home was somewhat dysfunctional. In your book after his death, you said Lee was everything to you, that you would be nothing had it not been for him. Talk a little bit about that. What is your relationship like, especially in the early years?

KF: My father wasn’t really involved with us that much. He was gone a lot. He was a professor. He taught at different places. His only relationship with us was as a disciplinarian. He often engaged in physical discipline with us. And my mother had her own mental health issues. She was paralyzed on the right side of her body from an assault that had occurred before we were ever born. And she had a stroke as a result of that. And so she was very paranoid herself, probably should have been treated in some way for it. So we had that dysfunction.

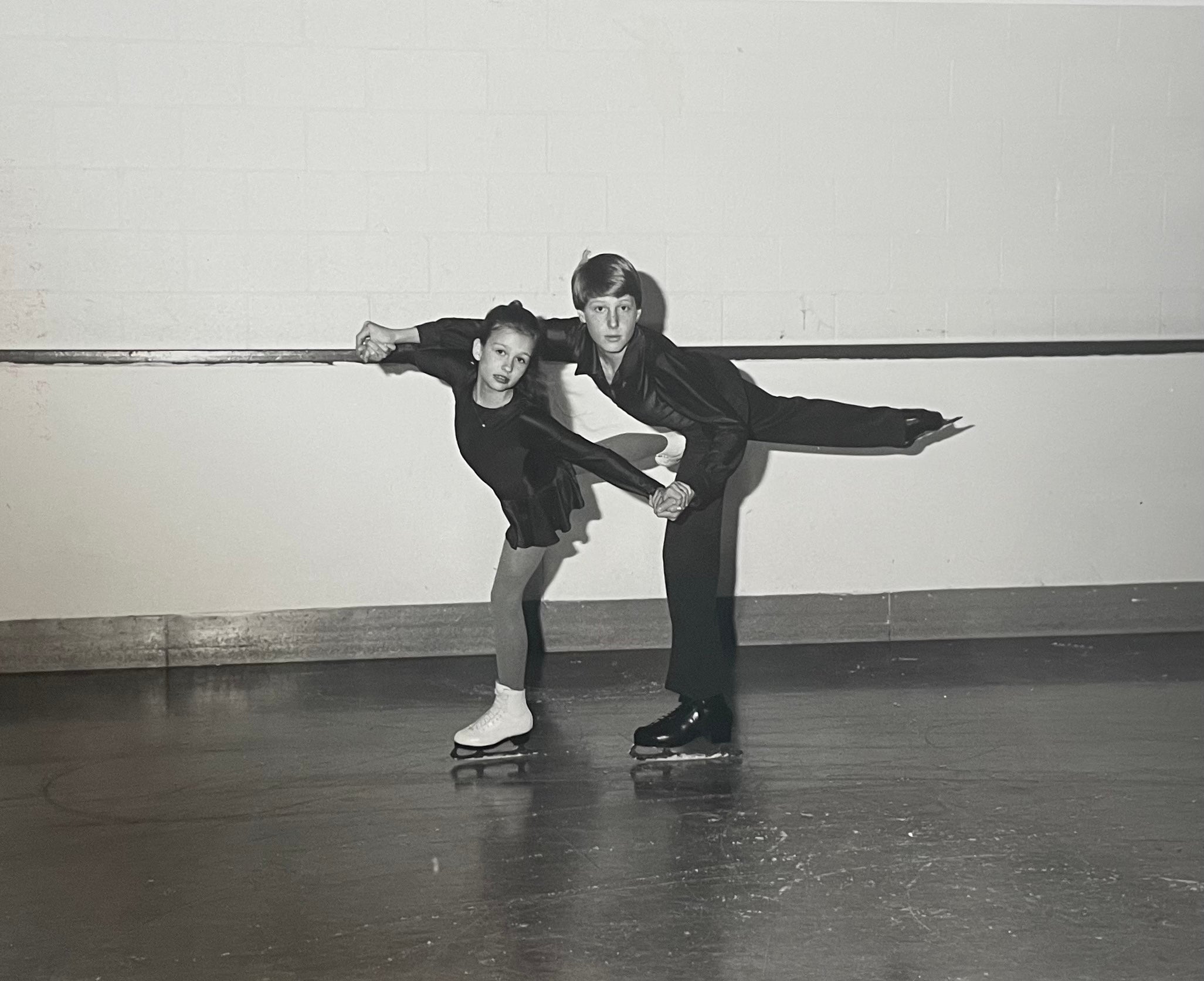

My brother was the rational person, ironically, in that whole process. He was my mentor. He was the one that got me to be an Eagle Scout. He was the one who taught me to read. He took the training wheels off my bicycle. He taught me how to throw a spiral. My dad had nothing to do with sports. My brother taught me those things.

And so my relationship with him was as a mentee to mentor. But once my brother started to have more and more symptoms, that role changed, where I was his mentor. I was the one that was counseling him. And that was a big change for me.

SS: Ken, when you finally made the decision to write this book, was it healing to you in some ways?

KF: I think so. Yes and no, for the most part. It was healing because I was able to express myself. And the whole process is healing because people come up to me and say, “I didn’t realize that you had been going through this.”

It feels a lot better as a result because at the time, no one seemed to care. And now they do. And that was good.

The bad part of it is … when you write a memoir, you’re pretty much exposing your life to the public. And I’m not sure if that’s a good thing. It can be a good thing. It can be a bad thing.

It gets you in a process of thinking about your life. And as a result of writing this, I’ve looked at all the things I’ve done wrong in my life, all the things I could have done better, all the regrets I’ve had, and perhaps I should have let those things go.

A lot of times we forget those things and so it doesn’t bother us anymore. But by writing a memoir, it…brings everything back. So there’s a price for that.

But I think at a certain point, maybe it’s better that you learn to let those things go. And part of the process of doing it is to confront it.

SS: When Lee died, you were surprised to learn how he touched the lives of other people. Talk about that a little bit.

KF: Well, initially, it’s like, what do I do for a funeral for my brother who’s schizophrenic, who I don’t think has any friends, and my parents were already dead? So I really didn’t do anything. I just had him appropriately buried by my parents and, you know, made the proper arrangements.

And I got a call a few weeks later, and it was from Lee’s group home director who said, “We want to do a tribute or a funeral for him at the group home.” I went there, we did it, and all the members of the group home were there.

And then we all sat in a circle and each had a chance to say something about my brother. And I just learned about all the ones that said good things about my brother. My brother taught them things in the way that he taught me things, so it was familiar to me. One of them said, “He taught me what E Pluribus Unum meant.” Another one said, “He taught me how to play chess,” which she did for me.

And so it kind of brought me back. And I was proud of my brother, for once.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.