Hmong pilots who served in the United States Army played a pivotal role in the Vietnam War — but their story has largely been hidden from the public, says Chia Youyee Vang, history professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and director of its Hmong Diaspora Studies Program.

Vang lets the pilots tell their own stories in her new book, “Fly Until You Die: An Oral History of Hmong Pilots in the Vietnam War.”

“Many things were classified until the 1990s,” she said. “You have the CIA officials who worked with the Hmong, the U.S. Air Force and also many American pilots who flew with them in Laos beginning to acknowledge that they actually have worked with these pilots.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

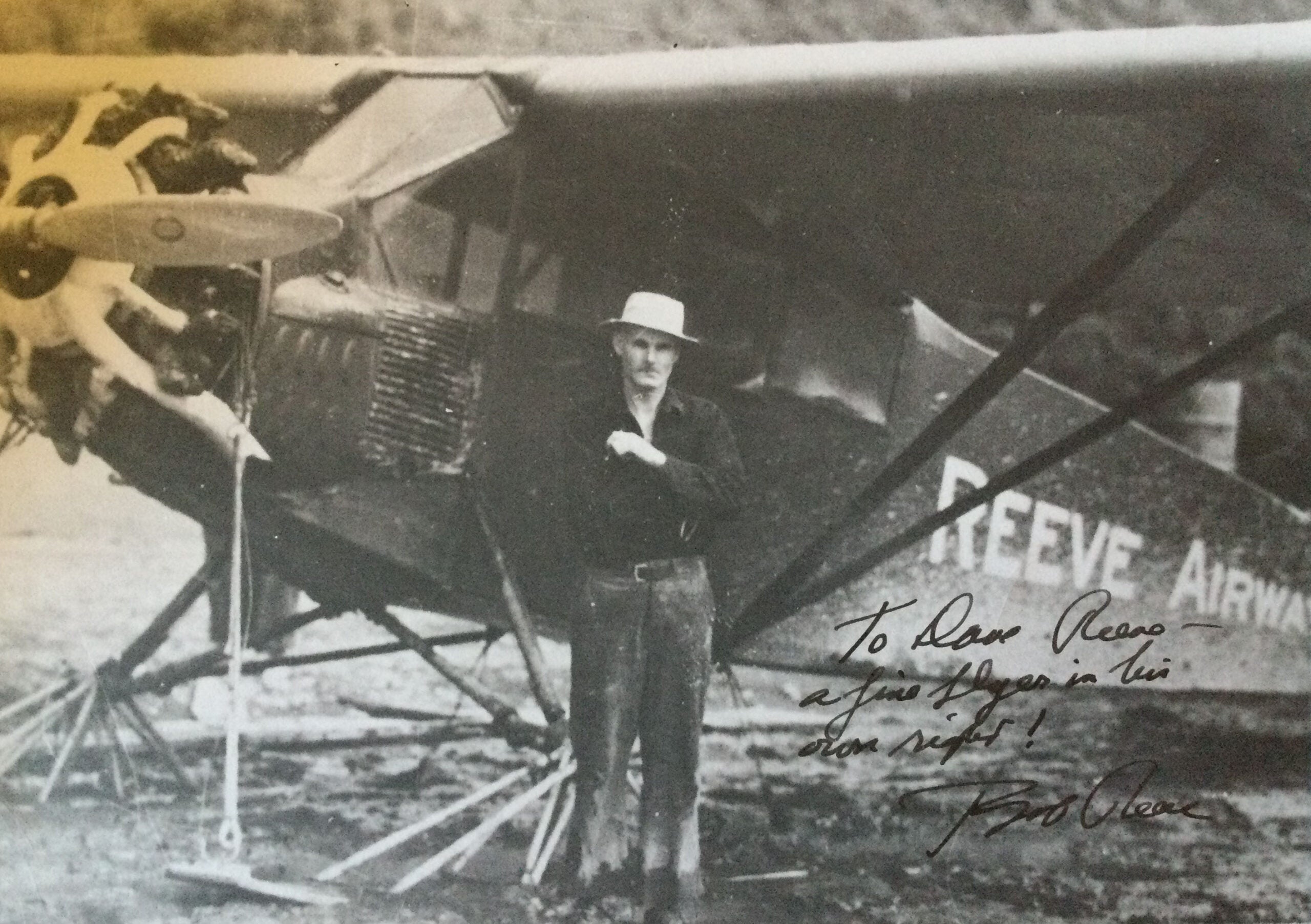

Tou Xiong Lee next to a T-28 aircraft shortly before he died in a crash. Photo courtesy of Chianaw Lee

It was a deadly task for the 36 Hmong men who were secretly trained to be fighter pilots — more than half were killed. The rate was so high because the men provided air support for ground troops, which meant they had to fly very low, Vang said.

When the CIA floated the idea of Hmong pilots it faced tremendous resistance from the U.S. military and civilian leaders, as well as Lao leaders, she said.

“The characterization of Hmong people has always been they were primitive, backwards, they don’t know much about technology or modern society,” Vang said.

Which led many to believe they couldn’t be trained to be pilots, she said.

“But because of the nature of the war … and in particular General Vang Pao who worked directly with the CIA … they let a few Hmong begin to train,” Vang said. “And the Hmong men did really well.”

The men who were selected to train were the elite of Hmong society at the time, she said. On average, the men had a middle school education, and several went on to get degrees from the National University of Laos.

But it wasn’t easy, she said.

“They had to learn English … and the men had to overcome a lot of barriers in terms of being an ethnic minority group that people felt weren’t suitable to fly these modern planes,” Vang said. “But then also to overcome all kinds of ethnic animosity and I think racism, as well.”

After the war, the majority of the Hmong pilots came to the U.S. and rebuilt their lives, she said, many of them wanting to forget about the war.

But Vang said the pilots she spoke to for the book said talking about their experience was “healing.”

“It’s very painful to remember because they have tried to forget for so many years, but now that they’re able to remember and to make sense of that particular time … it was a healing process for them,” she said.

But it also brought back pain and anger, she said, both at U.S. military leaders and policy makers and within the Hmong Army.

“Because they know now more than they did back then, back then they thought the war was about something different,” Vang said. “And then once they got to this country they better understood the larger geopolitical issues, and that brought some anger into some of the pilots who spoke.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.