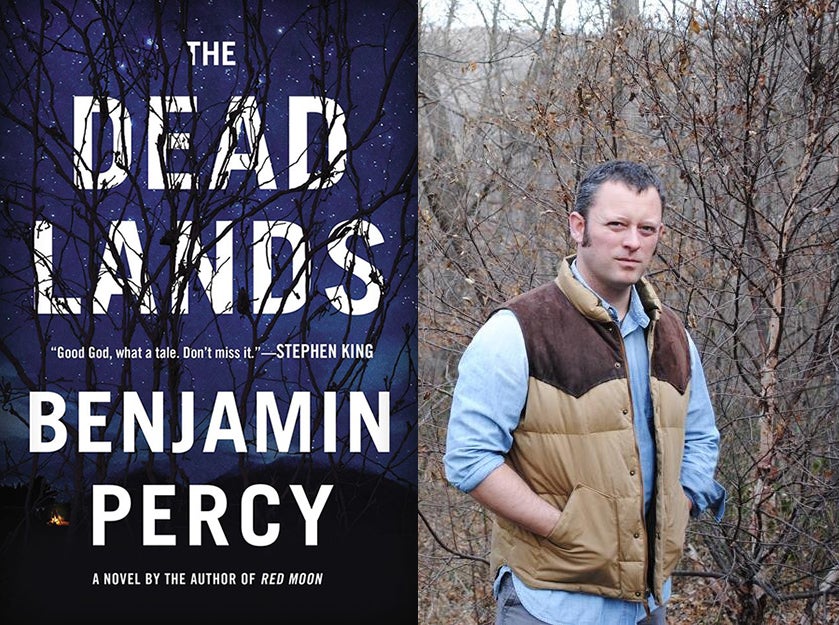

The latest novel from Benjamin Percy is a reason to keep the lights on. In the contemporary literary landscape, nobody writes fear the way he does — except maybe Stephen King, who is one of Percy’s many fans.

Percy’s latest is “The Dead Lands“, a frontier story with a twist: It’s set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, an America that’s been wiped clean by a combination of superflu and nuclear warheads. Into this devastated wilderness rides a small band of desperate heroes, led by none other than Lewis and Clark — fictionally reincarnated as Lewis Meriwether and Mina Clark.

Wilderness adventures are in Percy’s blood — he grew up hiking, backpacking and paddling in Oregon’s High Desert region before settling in the Northwoods territory of Wisconsin and Minnesota, where he passes the long winters by telling really scary stories to his kids.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Below are excerpts from a conversation with Percy that appeared on “To the Best of Our Knowledge.”

The state of Oregon — where you grew up — is Lewis and Clark territory. Was their story a big part of your childhood?

It’s been forced into my DNA to think of their story as essential. My mother is an amateur historian and every vacation we went on, every rock hounding expedition or camping or fishing or hunting trip, inevitably included a stop along either the Oregon Trail or the Lewis and Clark Trail. She’s been lecturing me since I was nine years old about how theirs was the greatest adventure story in American history. When I was 12, she gave me a copy of “The Journals of Lewis and Clark,” inscribed with a message: “Seek adventure.”

“The Dead Lands” reimagines their story through the eyes of their descendents, Lewis Meriwether and Mina Clark. Can you sketch things out a bit? What’s the situation when the book opens?

This is Lewis and Clark 2.0, so 150 years in our future. The world is a husk as we know it. St. Louis believes itself to be the last outpost of humanity. The downtown area has been fortified by a perimeter of stacked, rusted, mortared vehicles and an autocratic government rules this place. There’s a rebellion, of course, and out of the wastelands — out of the Dead Lands — comes a rider one day, proving that life still does exist and promising greener pastures in the Oregon territories. And so our expedition sets off.

Some of the scenes of this burned out world are so vivid: school buses filled with the skeletons of dead children, crazy lone survivors barricaded in ruined McDonald’s. Did you drive around your neighborhood trying to imagine what it would look like after a pandemic?

Falling off the grid has always been an active part of my fantasy life, so I guess it didn’t take too much of a leap of the imagination to see those skeletons lying all about and to see those radioactive, mutant albino bats swooping from the sky.

In some ways this is becoming a familiar scene. We’ve all seen the movies and TV shows: “The Walking Dead,” “Revolution.” Why is this post-apocalyptic wilderness such a powerful meme right now?

Destroying the world has never been more popular because destroying the world has never seemed more possible. You look at the news and you see a bomb exploding at the finish line of the Boston Marathon, you see the threat of Ebola, you see that California is crisping up into nothing. This is the safest time in history; we’re all safety-belted and helmeted and air conditioned and lotioned, and as a result of this anything that intrudes scares the hell out of us.

And the frontier for Lewis and Clark must have been pretty damn scary.

Yeah, I mean here was Louisiana, coveted by the French, by the British, by the Russians, by America. Everybody wanted it and then Napoleon sold it to Jefferson for $15 million, and in doing so he doubled the size of this country. But no one really knew what was out there — I should say no white people knew what was out there — and people truly thought that there might be woolly mammoths out there. It was the equivalent of an expedition to the moon. And so just think of the guts that would take and think of the wonder and the terror they would feel as they set off.

I love the way you’ve re-imagined the Lewis and Clark expedition a hundred and fifty years into our own post-apocalyptic future. Did you do that to get us back to what Lewis and Clark might actually have felt when they set off into the wilderness?

Initially, I thought maybe I should write this in a historical mode, but I didn’t know that it would be as relevant. I didn’t know if people would feel as tapped into it, so I thought the post-apocalyptic lands might give contemporary readers a viewpoint that felt more scarily real.

Did the landscape become a kind of character? Can landscape be a character in a way that goes beyond physical description?

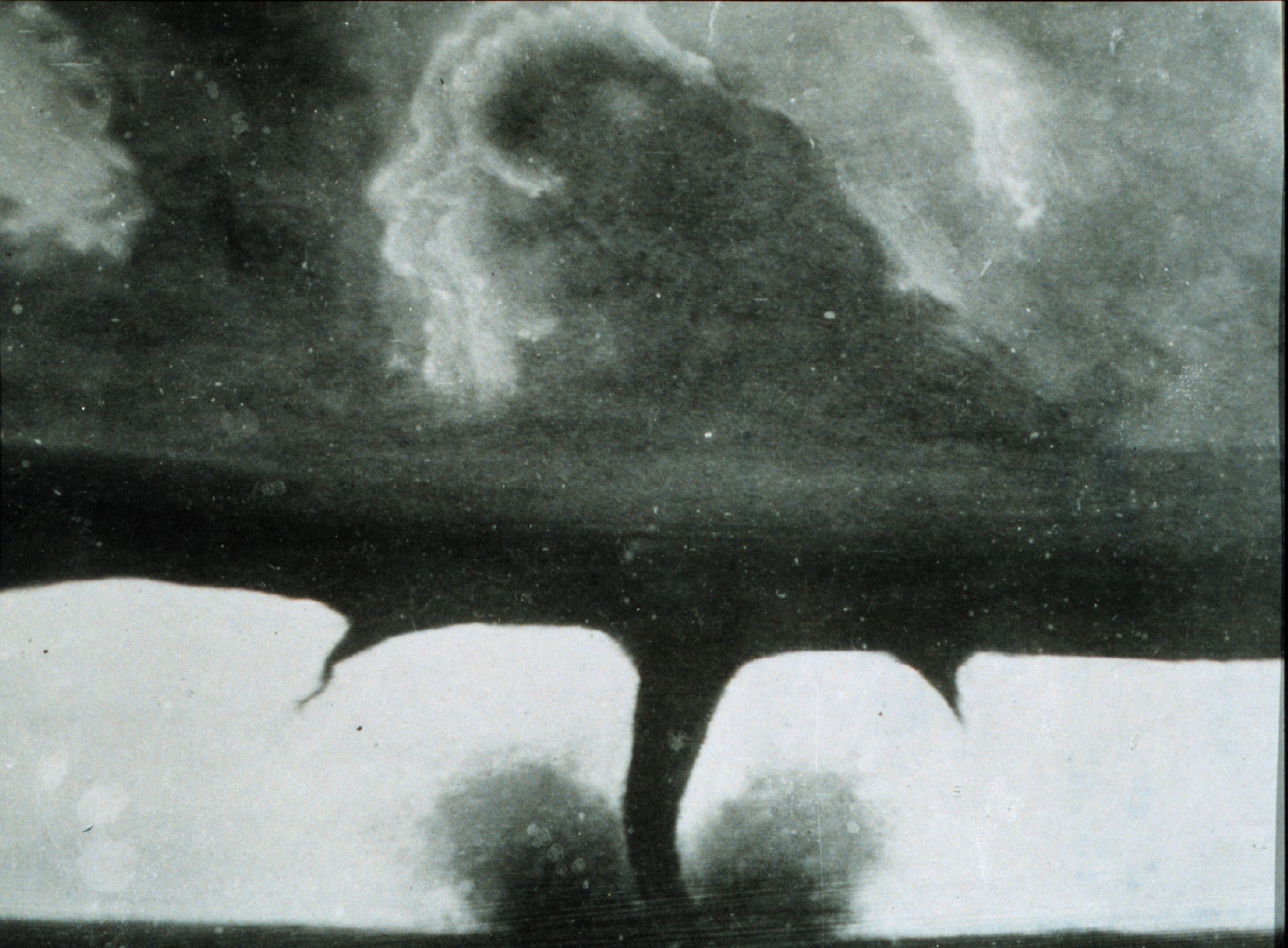

Absolutely. I don’t teach anymore, but when I was teaching, I would always tell my students to write about their own backyard, to write about their own 40 acres. And I’m not just talking about the geography of the place; I’m talking about the history of the place. I’m talking about the politics, the culture, the myths of the place. In Iowa, for instance, when I was teaching there, we’d talk about the way that at any moment a tornado might come unfurling from the sky and vacuum up the earth, or the way that, in certain places, the air smelled like blood near a hog-butchering plant, or the way that the floods would come and wipe out a town, like an inland ocean. And every town has these stories that you can mine onto the page. The places you know best are the places you grew up.

You’re talking about developing a literary geography or sense of place. Maybe that’s what we’re all hungering for, in our increasingly homogeneous landscapes. The way things are now, you can drive from one end of this country to the other and eat at the same restaurant the whole way.

It’s a weird thing. Maybe we always want to feel like we’re home, no matter where we are? It’s really boring, the idea that you would go to some new city and eat at Applebee’s.

But how do you find that sense of place you’re describing? Because a lot of us would probably say that where we live is boring or uninteresting.

And that’s probably encouraged by the fact that so many of us are full-time indoorsmen, the fact that we rarely get out-of-doors anymore, that we go from our living rooms to our cars to our workplaces and back, maybe with a stop at the grocery store or shopping mall. If everything in our life is fluorescent-lit, then we have no sense of connection to the world that has shaped us. That bothers me. It’s why every chance I get, I try to force my kids out the door. We live on four acres of woods in Minnesota and we try to get to the lakes as often as we can, or go camping, or visit my in-laws’ family farm outside Eau Claire. I want my kids to have a sense of the world that goes beyond the screens held in their hands.

Did you spend a lot of time outdoors yourself, as a child?

Well, I grew up in a sort of strange way, although I didn’t realize this at the time. My parents were back-to-the-landers. My father harvested all the meat that we ate: elk, venison, bear. I grew up on a steady diet of bear, which is why I sound like this. My father was an obsessive rockhound, so our weekend adventures involved excavating geodes and petrified logs from scat land. I guess because of this I have a better sense than some about the world that has shaped us. I have a better sense of being dwarfed by the landscape. I’m messing with that in my writing, and with the way landscape can call attention to human activity.

You play with that in your writing and even in social media. I remember seeing a Facebook post of yours last winter; somebody had asked you about your writing routine and you wrote this hilarious thing about swimming naked in frozen lakes before writing every day.

Dont’ forget that I rode naked on the back of my dire wolf named Grue to get to that frozen lake.

Now I’m remembering you also posted something not that long ago about “man camp.”

Oh yeah, man camp. This guy in town felt frustrated by the fact that dudes never really interact the way women interact. We don’t have social gatherings, or if we do, we watch football and don’t say anything except “Rah, rah.” So the idea for man camp is to get outdoors. We do this in the middle of winter and we head up to the shores of Lake Superior. The last time, I think it was 26 of us and it was cross-country skiing and snowshoeing and lots of boozing, of course. The highlight was the midnight sledding with the nimbus of clouds around the full moon, and then all of us going down this incredibly, suicidally steep hill with our headlamps glowing and — just one after the other after the other — making this slick blue ribbon, this track that we all move through, and our voices hooting all around, joining up with the chorus of wolves in the woods. It was pretty amazing.

It’s so romantic but it also sounds a bit Ernest Hemingway. The men, the wilderness, so many things to hunt and catch and trap.

I was just worried it was going to end with a shirtless drumming circle. Thankfully that didn’t happen.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.