Poet and author Kevin Young traces the history of the hoax. Also, writer Susan Orlean shares the story of the biggest library fire in American history. And we explore “the front page of the Internet,” Reddit, with journalist Christine Lagorio-Chafkin.

Featured in this Show

-

Author Kevin Young On Why We're Attracted And Appalled By Great American Hoaxes

When The New Yorker’s poetry editor and author Kevin Young was an editor for Harvard’s “Let’s Go” book series, his publisher was Ravi Desai. Desai was so well regarded in the offices that it wasn’t surprising that many of his peers cried when Desai announced he had cancer.

Years later, it would be unveiled that the diagnosis was a hoax. Desai went so far as to shave his head to mimic receiving chemo treatments. He would go on to perpetrate several large-scale hoaxes including defrauding universities and duping online publications.

Thus began Young’s rabid interest in America’s deep-rooted history in hoaxes. What began as a “slim mediation” on the subject ballooned into a comprehensive treatment of great American hoaxes that became Young’s book, “Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News.”

“For me, it wasn’t even so much personal as I became fascinated by the history of this. I started to really realize that the hoax had a long history, especially in the U.S.,” Young told WPR’s “BETA.”

Young asked himself if the idea of the hoax was a “particularly American” phenomenon. While he acknowledges that it didn’t originate in the United States, we’ve long embraced it.

“The idea of the con artist and con man is an American phrase and idea and we sometimes go back and forth whether we admire con men like in ‘Catch Me If You Can’ or other movies that glorify that or if we’re really upset with that,” he said.

Young traces this human instinct to be attracted, awed and angered by a hoax back to the 19th century. Young argues that famed showman, P.T. Barnum, was able to channel this appetite for curiosity into a successful spectacle.

“That’s when the hoax really takes off and goes from something some one individual might conjure up to something P.T. Barnum perfected and turned not only into a show, but a national treasure and technique,” Young explains.

Young identifies how this time-period also overlaps with the evolution of our societal definitions on race. He argues that race and hoaxes go hand in hand because they are both fake entities pretending to be real.

“I came to really understand that in the 19th century – where I traced the hoax from and P.T. Barnum – is really when our modern ideas of race and different races and what the particular races are and these kind of hierarchies of race evolved,” he said.

“Race itself is this way that people separate themselves and divide themselves and they use it often to fake from and with,” Young said. “That kind of divide that people use is one the hoax goes to all the time.”

More recently, Young turns to famous journalistic hoaxes like those of Jason Blair, Stephen Glass and Janet Cooke.

“Those figures are fascinating and they hoaxed at The Washington Post and The New York Times and The New Republic, so across very prestigious journalism,” Young said.

“Why do people believe these stories, that when you look back on them are so obviously fake,” said Young. “But, one of the things I realized about the hoax is believability is actually not what it’s going for. It’s going for the outrageous so it’s so unbelievable, you hardly have time to stop and think.”

“I started the book really trying to understand why we deceive each other. By the end, I really started thinking about why we believe. Why do we believe the worst of each other? Why are things as bad as we fear they are in the hoax,” Young said.

The popular journalistic hoaxes serve as a natural progression into our current climate of “fake news” and misinformation with the crowd having ready access to a platform.

“I think what’s interesting about the moment now that we’re in is that it isn’t just that fake news is something that people are concerned about, but it’s an accusation that then invalidates all news,” said Young. “Instead of saying, ‘I’m going to hoax you,’ I’m going to call you a hoax. That’s the ultimate insult right now.”

Young hopes his book outlines why we are susceptible to hoaxes as a culture and how we arrived at this point so we can better operate in a world that perpetuates fakery.

“Working on this book has made me hopeful about it. It sort of gives us a sense of at least where we’ve been and that sometimes we’ve been in bad places of fakery,” Young said, “but also that means there’s a chance that we can get past that.”

-

Author Susan Orlean Uncovers Story Of Most Devastating Library Fire In US History

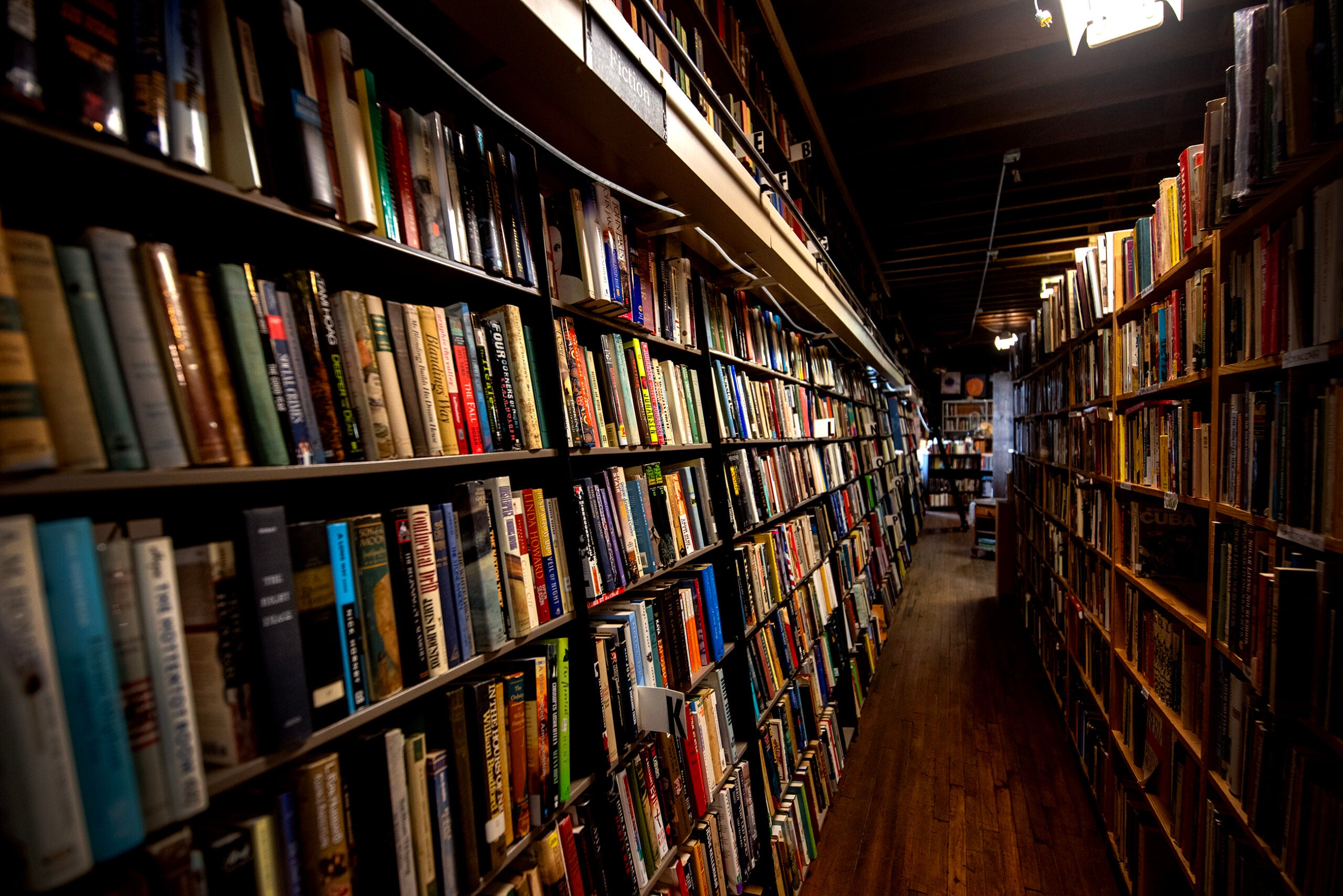

Susan Orlean is an author and a staff writer for The New Yorker. Her latest book, “The Library Book,” is an intoxicating mixture of true crime, history, biography and immersion journalism.

It tells the story of the most devastating library fire in American history — the Los Angeles Public Library fire in April 1986. The fire burned for more than seven hours and destroyed 400,000 books. Orlean found out about the story accidentally, while on a tour of the Los Angeles Central Library.

“As we were walking through the building, the gentleman giving me the tour pulled a book off the shelf, took a deep whiff of the book,” Orlean told WPR’s “BETA.” “I didn’t really understand what he was doing. And he, after a moment, said, ‘You can still smell the smoke in some of them.’ I thought he meant that they allowed people to smoke in the library. I really had no clue about anything that would be referring to a fire. And he said, ‘No, no, no. From the fire, the big fire.’ And I said, ‘What fire?’ And he said, ‘Well, the big fire in 1986 that shut the library down for seven years.’”

Orlean was astonished that she had never heard of the fire. She said that was a big reason why the story appealed to her. The more she learned about it, the more surprised she was that she wasn’t familiar with the story of the biggest library fire in American history.

It happened on the morning of April 28, 1986. The library was open and there were about 200 patrons inside along with about 200 staff members.

“When the fire alarm went off, nobody was especially concerned because they had a lot of false alarms,” Orlean said. “The building was in bad shape, the fire alarm system was very touchy, so people thought, ‘Oh God, here goes another false alarm.’ They evacuated the building, the fire department showed up, looked around, didn’t see a fire, couldn’t reset the alarm, thought they better look again and found a little tiny sort of tendril of smoke in the fiction stacks. Very quickly, it exploded into an enormous fire that ended up reaching 2,500 degrees. It burned for seven-and-a-half hours — just fierce, fierce fire that was burning in the stacks of the library, which are almost like big chimneys that are lined with books.”

Orlean said the fire became so hot firefighters told her, “that the flame became colorless. It wasn’t red, it wasn’t orange, it wasn’t blue. It was just clear. And they said it was really terrifying.”

Four-hundred-thousand books were totally destroyed and 700,000 were badly damaged. But the building remained basically intact.

Aside from the incredible damage done to the books, Orlean said there was a lot of psychological damage done to the people who worked there.

“It was really devastating. The librarians were traumatized,” Orlean said. “Librarians work diligently to build their collections. It’s not just that they click on the best-seller list and order those books. They’re developing collections that they feel are really interesting and comprehensive and relevant to their patrons. For them, seeing their work up in smoke literally because of the fact that they developed these collections, the fact that they had no idea what was going to happen, if the library would ever reopen, their concern about what was going to happen to their patrons, the people who use the library.”

Investigators began to suspect arson and the prime suspect was a young man named Harry Peak.

Peak grew up outside Los Angeles. With visions of movie stardom, he moved to the city and began working odd jobs, all the time imagining it was only a matter of time until he became a star. He even told his family that he was becoming friends with celebrities like Burt Reynolds and Cher.

“The thing about him is that he lied about everything but never in a way to harm anyone,” Orlean said. “It was innocuous, silly lies. But he was a liar. He may be the most unreliable narrator. I’ve never heard of an instance where someone provided so many different alibis.”

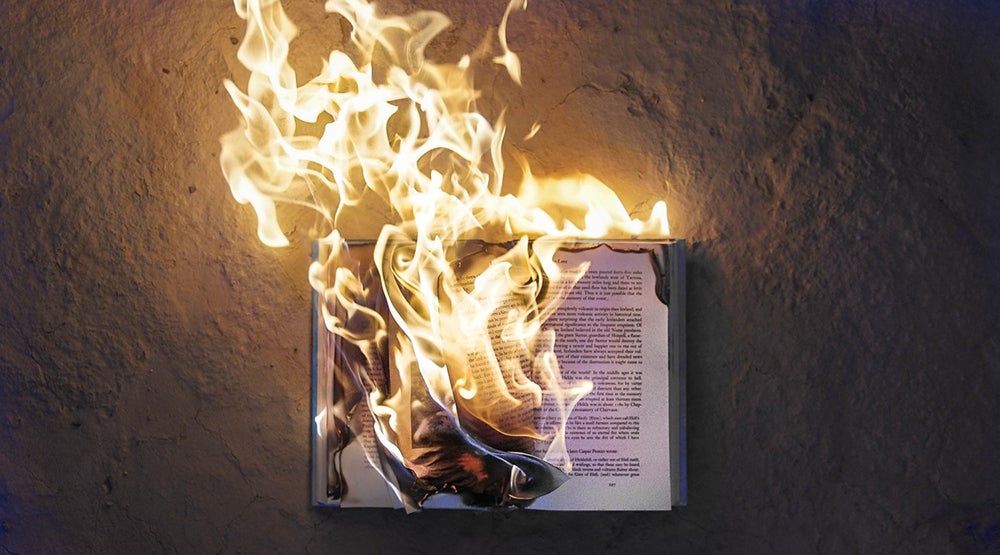

At some point during the writing of her book, Orlean realized she’d never seen a book burned and so she had no idea how to describe it. So she decided to burn a book.

“I was very curious about our relationship to books and libraries and why they feel almost sacred. And why there is such a taboo about not only burning a book, even throwing a book away. I realized that I couldn’t remember ever throwing a book away, including books that were literally falling apart. I just found it so uncomfortable as if it were a living thing,” she said.

Orlean had a difficult time deciding which book to burn. At first she thought she’d burn a book that she didn’t like, but that seemed harsh. Then she thought she’d burn a book that she really liked but then realized that she couldn’t do that either. After deciding she couldn’t burn one of her own books, she thought her experiment may be ill-fated. Fortunately, her husband made the decision for her.

“One day, my husband came home and he was just grinning ear to ear. And he handed me a copy of ‘Fahrenheit 451’ by Ray Bradbury and said, ‘Here you go.’ And I really did feel it was the perfect book to burn and Ray Bradbury would have appreciated it,” Orlean said.

So how did burning a copy of Ray Bradbury’s classic novel go?

“Well, I was very nervous because I was in L.A. and I thought burning anything in L.A. is a very risky undertaking. So I went to my backyard and I took an aluminum cookie sheet, which I thought would be a safe kind of base to burn the book on. I had my husband come out with me with a bunch of buckets of water. I was really nervous,” Orlean said. “I finally lit a match and held it to the corner of the cover. And it was slow in the beginning. It was just a little trickle of smoke and a little edge of orange. And then suddenly the book literally was gone. It was almost as if it had exploded, it burned so fast.”

Orlean said her personal experience with book burning gave her a better understanding of how the library fire became so fierce.

“Books are perfect fuel and particularly, when they’re in what is essentially a chimney,” she said.

-

The Tumultuous History Of Reddit, 'The Front Page Of The Internet'

Christine Lagorio-Chafkin grew up on a sheep farm in rural Wisconsin. Now she lives in New York City where she works as an award-winning journalist.

For the last 15 years, Lagorio-Chafkin has covered culture, emerging technologies and entrepreneurship. She’s also the author of a book called “We Are The Nerds: The Birth and Tumultuous Life of REDDIT, the Internet’s Culture Laboratory.“

Christine Lagorio-Chafkin. Image courtesy of Westin Wells“Reddit is kind of this sprawling universe of communities online for just about everything under the sun,” Lagoria-Chafkin told WPR’s “BETA.” “There are 140,000 (communities). And it’s everything from a massive community for women called ‘2XChromosomes‘ to stop-smoking communities. There’s humor, there’s talk about movies and video games. And every sports team that’s ever existed has a subreddit. It’s the fifth most popular site on the American Internet. And people type into it more than 50,000 words every minute.”

Lagorio-Chafkin said one of the reasons we don’t hear as much about Reddit as we do about Facebook and Twitter is that there is a dark side to some of Reddit’s content.

“Where Facebook and Twitter don’t, Reddit does host pornography and has all sorts of conspiracy theory communities. It’s got a lot of political discussion and a lot of ultra-conservative political discussion. So there are dark corners to the site in the way that you might not encounter those sorts of things if you just visit Facebook to look at your friend’s stuff or Twitter,” she said.

But Lagorio-Chafkin points out how user-friendly Reddit is because the subreddits are organized by subject into user-created boards which are kind of like sub-websites within websites.

“Basically any user who comes to the website can ‘upvote’ or ‘downvote’ … on any single post,” Lagorio-Chafkin explained. “Now an upvote is not the same as a Facebook like, it is not endorsing the viewpoint of the content. It’s simply saying this is important. So by giving Redditors — the name Reddit calls its users — the power to determine what rises up on a page or what sinks down … it basically democratized the job of say editors at a newspaper.”

While Lagorio-Chafkin admits there are both benefits and downsides to user-controlled prominence, the Reddit model essentially showed the rest of the internet the value of community input.

But as Lagorio-Chafkin explains it, Reddit’s co-founders, Steve Huffman and Alexis Ohanian, had something completely different in mind in 2005 when they first set about developing a new kind of website. Instead, they hoped to create a mobile food-ordering app called MyMobileMenu — or MMM.

“It was basically … any kind of food-ordering app that you might use on your phone. But back in 2005, apps did not exist. So they had no way of actually creating a way to get your phone to simply give an order to the restaurant and get that food back to you,” Lagorio-Chafkin explained.

Huffman and Ohanian took their idea to the prolific programmer Paul Graham who would go on to become very famous for founding the influential Silicon Valley incubator, Y Combinator. Graham sold them on the idea of a completely different business venture: “What if you build only a page where the most popular headlines and posts from around the internet for that day will live. It’ll be the front page of the Internet,” Lagorio-Chafkin said.

Huffman and Ohanian agreed and Reddit was born. As the website grew, Redditors took advantage of the site’s open-source, pro-free-speech philosophy.

“One of the sort of taglines that arose out of that was ‘freedom from the press.’ And Reddit gained the reputation as being a super free-speech haven. And therefore, avid Redditors decided constantly that they were going to try to test the limits of what was free speech, you know, what was OK to post. And therefore entire ecosystems of sort of the darkest stuff that you can imagine — photos of highway crashes, very strange pornography sort of emerged in dark corners,” Lagorio-Chafkin said.

As Lagorio-Chafkin writes in her book, “Reddit was a place where the crowd decided what was deeply interesting. To avoid that ‘gatekeeper’ effect, the people operating the site should be hands-off and let the community be self-organizing.”

Which raises the question: How did the community managers at Reddit deal with the creation of offensive content?

“These (community managers) are exposed to horrific images every day. They are the people who when you get sent a photo that you would not like to see and report it to a social network, those people have to look at that image and say, ‘Oh,yes, I’ve got to tell that guy not to send that kind of image anymore,’” Lagorio-Chafkin said. “At that time, the job was a very new thing. They did not have therapy sessions for community managers built into their business model at the time. So as it evolved, these people were actually kind of making the job up as they went along. They were reporting suicide attempts to the FBI, they were reporting bomb threats, they were doing their best to kind of help humans help each other. And yet they were subjected to kind of horrible things every day during their job, making it very, very difficult to make those content decisions.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Doug Gordon Producer

- Adam Friedrich Technical Director

- Kevin Young Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.