For a four-person crew, managing 3,200 acres of property can be daunting. Add climate change to the mix, and it only complicates matters.

Yet for Justin Nooker, a 32-year-old habitat biologist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, this is a project of a lifetime. He’s one of many partners working on implementing the state’s first grassland climate adaptation site at the Rush Creek State Natural Area.

“For me, it’s been inspiring,” he said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

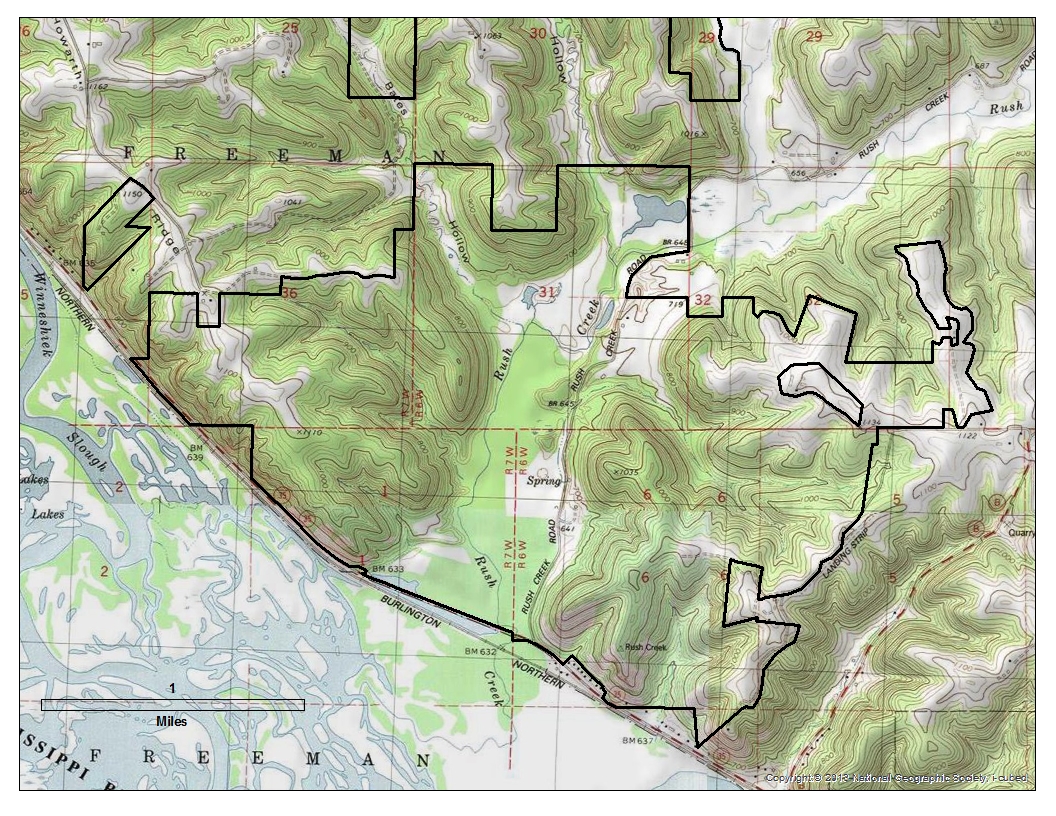

The Rush Creek State Natural Area — about 30 miles south of La Crosse — supports nearly 50 rare or declining species. It’s a designated important bird area. And it’s one of the largest remaining prairies in the Midwest.

Rush Creek, owned by the DNR, has been a State Natural Area since 1981. Property managers have been working on it for years, but the project marks the first time multiple environmental groups are teaming up to bring climate resiliency and explore new management approaches at the site.

The project started in January, with a majority of funding coming from a $300,000 grant from the Wildlife Conservation Society’s climate adaptation fund. Other groups involved include the Wisconsin Natural Resources Foundation, the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science and the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, or WICCI.

Caitlin Williamson of the Natural Resources Foundation said it’s a project long in the making.

“It’s really unparalleled in the state,” Williamson said. “Its size, the scale of the work … and all the thoughts of many different partners that have gone into this to design it in a way that’s, to the best of its ability, planning ahead for expected climate changes.”

Adapting and mitigating the effects of climate change

DNR conservation biologist Amy Staffen said the site is a “best case scenario” for facing climate change.

With warmer temperatures, an increase in precipitation and spring arriving earlier, it’s become much more difficult for property managers to prescribe fire — what Staffen and experts say is one of the most important tools for managing natural communities like prairies.

“A lot of our native species, plants, animals, wildlife co-evolved with fire on the landscape,” Nooker explained. “If we aren’t able to prescribe that fire on the landscape, then those species are at higher risk of disappearing.”

Since 1950, temperatures have risen by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit, and average precipitation has increased by 17 percent — or 5 inches — according to a 2021 WICCI report — making the last decade the wettest on record for the state.

“I feel like we’re offering empowerment to property managers who have been faced with a really daunting threat — this big threat of climate change,” she said.

To help, Staffen is connecting property managers with an adaptation workbook they can use to “approach climate change with intentionality and logic.”

Nooker said come winter, the property managers will work on making systems more resilient through brush cutting and strengthening the woodland oak forests.

Jack Williams, a climate scientist and chair of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Department of Geography, explained that prairie plants, with their deep roots and soil horizons, can store carbon and mitigate climate.

“There’s a lot of below-ground carbon sequestration in grasslands,” Williams said. “So a healthy grassland can also be a good climate mitigation strategy.”

Property managers are also implementing an approach called regional admixture provenance. It involves collecting seeds of prairie plants from various locations and mixing them together to strengthen its genetic diversity.

“This effort is striking a careful balance where they’re not just taking seed sources from just anywhere, but they’re kind of working within a regional framework,” Williams said.

Ellen Damschen, a UW-Madison professor in the department of biology, echoed that view, stressing that it’s important because small, local seed populations are at greater risk of getting wiped out.

“If seeds move, they’re moving their genes. You want to allow population sizes to get bigger, and you want to allow movement between sites,” she said.

Still, the work is ongoing.

“These systems are disturbance-dependent natural communities,” Nooker said. “In essence, we’re never gonna be done managing them — they’re always going to require inputs.”

Group will host field trips to the site as work progresses

The project started in January, with land managers already working on ecological restoration activities including: invasive species removal, brush clearing on prairies, creating savanna strip buffers and planting oak trees. They’ll also turn some agricultural fields into high diversity prairie plants to “expand the habitat,” Williamson said.

With plans to assess their progress and success with protecting the site, the Natural Resources Foundation will offer field trips over the next couple of years for the public to visit Rush Creek. Williamson and project leads hope their work inspires conservationists and land managers around Wisconsin.

“While we can have hope that natural area managers are tackling climate change the best way they can, it’s still absolutely vital that we continue to mitigate the impacts of climate change by what we do as human beings,” Staffen said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.