Since 2009, there have been at least 17 deaths among workers on Wisconsin’s dairy farms. Nearly half of those were not investigated by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

ProPublica reporter Melissa Sanchez has been reporting on safety in Wisconsin’s dairy industry and why these deaths haven’t gotten more scrutiny.

Sanchez joined WPR’s “All Things Considered” host Brady Carlson to talk about her findings.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

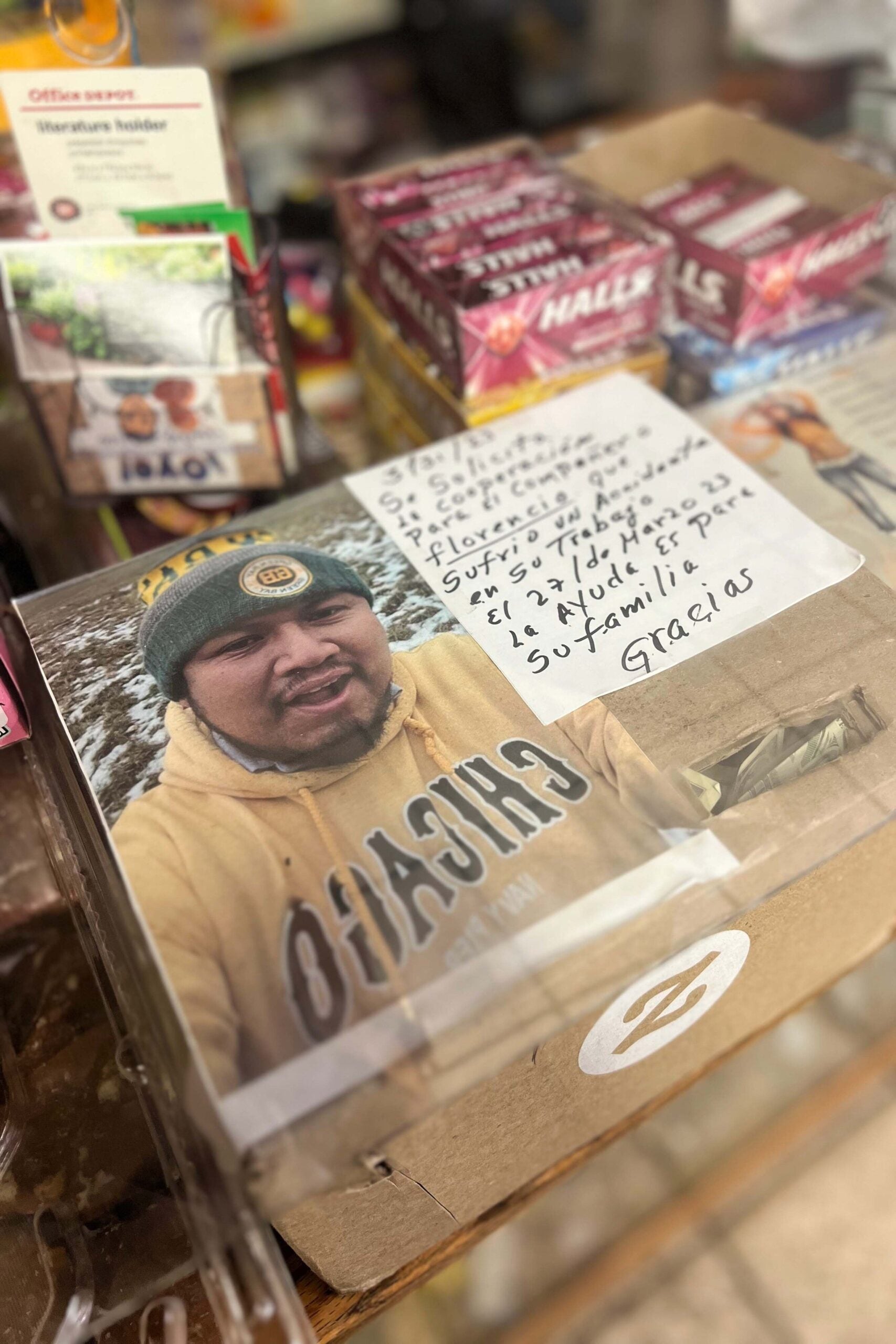

Brady Carlson: To start, let’s look at a recent case in March 2023. Florencio Gómez Rodríguez drowned after he drove a skid steer into a 14-foot deep pond filled with manure on the dairy farm where he worked. Why was there, after this tragedy, apparently no OSHA investigation?

Melissa Sanchez: OSHA has been around since the 70s. But basically, right when it started, Congress put a special exemption into place that exempts small farms from inspections. And so, farms with fewer than 11 workers and farms that don’t have what’s called a temporary labor camp do not get inspected by OSHA.

So in this case, an OSHA inspector went out the morning after Florencio died and turned around and left after less than an hour after discovering the farm had only seven or eight workers. So that’s generally what happens on small farms. But we looked into this because of the temporary labor camp issue and housing.

BC: Because that reasoning has been given in a number of other cases. You looked at this, and you found that in these cases where OSHA said, “Well, there’s no temporary housing exemption to give us the authority to investigate here.” … It wasn’t always as simple as it sounded.

MS: Across Wisconsin, dairy farms routinely provide housing to immigrant workers. Housing can be on site, housing can be at an apartment nearby. It’s pretty standard — and many of these workers are undocumented.

What we found in OSHA’s own records is that, over the years, OSHA has repeatedly called this type of housing a temporary labor camp. This would give it a jurisdiction to inspect, but OSHA has not been consistent in this interpretation.

In the case of Florencio, even though he lived in a house down the road with a bunch of other workers, the house was provided by his employer. OSHA did not inspect the farm. We asked OSHA about this: Why didn’t you inspect when there was housing?

OSHA initially said that the inspector who went to visit didn’t find housing, but even after we told them about the housing and provided evidence about it, they said that there was no temporary labor camp. So it’s very confusing and OSHA has been very inconsistent about what it called the temporary labor camp.

BC: As you mentioned, the workers that you highlighted in this piece were all immigrants lacking permanent legal status, something that was largely known by the employers. How does this heighten risks for farmworkers?

MS: One of the obvious things is language. Often, farmers and their workers can’t communicate with each other. And what winds up happening is that workers aren’t trained properly because they don’t speak the same language on things from how to use a skid steer properly to just basic safety issues. If you’re undocumented, you’re a lot less likely to speak up or complain about safety issues or other problems, for fear of job loss or fear of deportation.

Undocumented folks end up having a lot of debt when they come to the U.S., so they’re incentivized to work a lot of hours. They frequently work 70 to 80 hours, which makes you exhausted and more than likely to be in situations that are risky when you’re so tired.

There are a lot of reasons, but a lot of people don’t even know that OSHA exists, so they don’t know what their rights are. And farmers know that their workers are undocumented. It’s this open secret and unscrupulous farmers can use that to their advantage.

BC: What’s the response been to this reporting here in Wisconsin?

MS: We’ve heard from attorneys, from advocates and from workers, a lot of surprise that OSHA had ever inspected injuries or deaths on small farms.

I think a lot of people in Wisconsin and across the country who care about worker safety were shocked that OSHA had found a way in Wisconsin to do its job on small farms and also disappointment that OSHA has been inconsistent about it. We’ve spoken to the higher ups, former higher ups at OSHA who had no idea that OSHA had ever done this.

So I think what we’re hearing from folks is confusion about what OSHA is doing and a desire for more clarity about whether it would continue to view this type of housing as a temporary labor camp. And some more consistency, too.

To learn more about how OSHA investigates deaths on Wisconsin’s small dairy farms, read here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.