With all the articles, books and documentaries that have examined and reexamined the hallowed history of 1960s rock ‘n’ roll, it’s still surprising that an important group like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band remains unheralded for their crucial contributions to pop music. Put bluntly, if it weren’t for the Butterfield band, both the American blues revival and Age of Aquarius would have been very different, or not occurred at all.

Now there’s an opportunity for reappraisal as the Butterfield Blues Band will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in a few days — only 20 years later than many of its baby-boomer contemporaries.

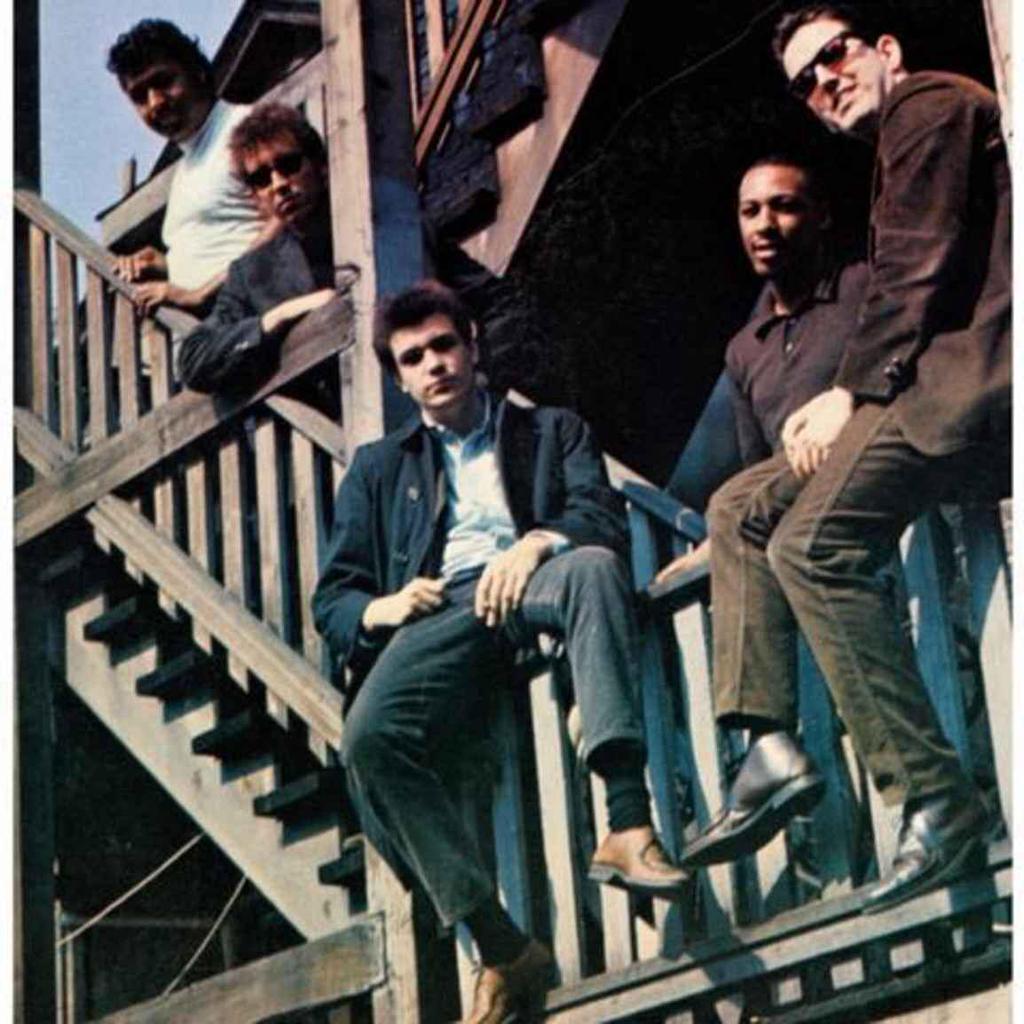

The Butterfield Blues Band, led by expert harmonica player Paul Butterfield, rhythm guitarist Elvin Bishop and a (literal) fire-breathing guitar hero Mike Bloomfield, was the original crossover act, presenting urban, electrified blues to white, suburban audiences and offered a rare Yankee response to the British Invasion bands. The band members were front-row students of Chicago blues masters like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter and Sonny Boy Williamson and others, and the Butterfield band sought to bring those sounds out of the Windy City club scene to a wider audience.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In the end, the band achieved this aim, but indirectly. Blues music was rediscovered, but it was through other, more mainstream acts like Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead or Led Zeppelin that the audience was reawakened to their forgotten cultural heritage

Rather than malice, it was the Chicago-based outfit’s key flaws — the lack of a charismatic singer and truly great songs — that kept the Butterfield band from achieving greater fame and fortune during their heyday and meant the group was largely overlooked in all the years after.

While those flaws are considerable and shouldn’t be undervalued, the reason the Butterfield band truly deserves wider appreciation can be based on their music’s inherent promise (although arguably undelivered upon) and how these musicians’ studious dedication to the blues effectively opened a door that served as a powerful example to many of their contemporaries.

In many respects, the band came along at just the right time. They were a kind of musical bridge between two eras, standing at a critical leaping-off point where Kennedy-era idealism flowered into flower-child mind expansion, musical experimentation and political revolution. Through the Butterfield band’s first two albums, their self-titled 1965 debut and 1966’s “East-West,” they helped introduce American blues to the hippie generation and was one of the first interracial combos to appear on the charts. Topping it all off, members of the group backed Bob Dylan during his first electric performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 and played on his seminal “Highway 61 Revisited” record.

At that time, future members of the Byrds, Jefferson Airplane or Santana were either in high school or playing acoustic guitars at folk clubs. The Butterfield band, however, were playing the rough-hewn blues at full volume. The band’s records were well-regarded for the time because of how unique, foreign and explosive their sound was to those accustomed to the sonorous perfection of Joan Baez and her fingerpicking technique.

Although Butterfield’s song choices veered between the obvious to the underdeveloped — their best-known cut, “Born In Chicago,” hits hard but has none of the melody or lyrical grace of the blues standards it seeks to emulate — it’s the band members’ commitment to authenticity and passionate delivery that carries the day.

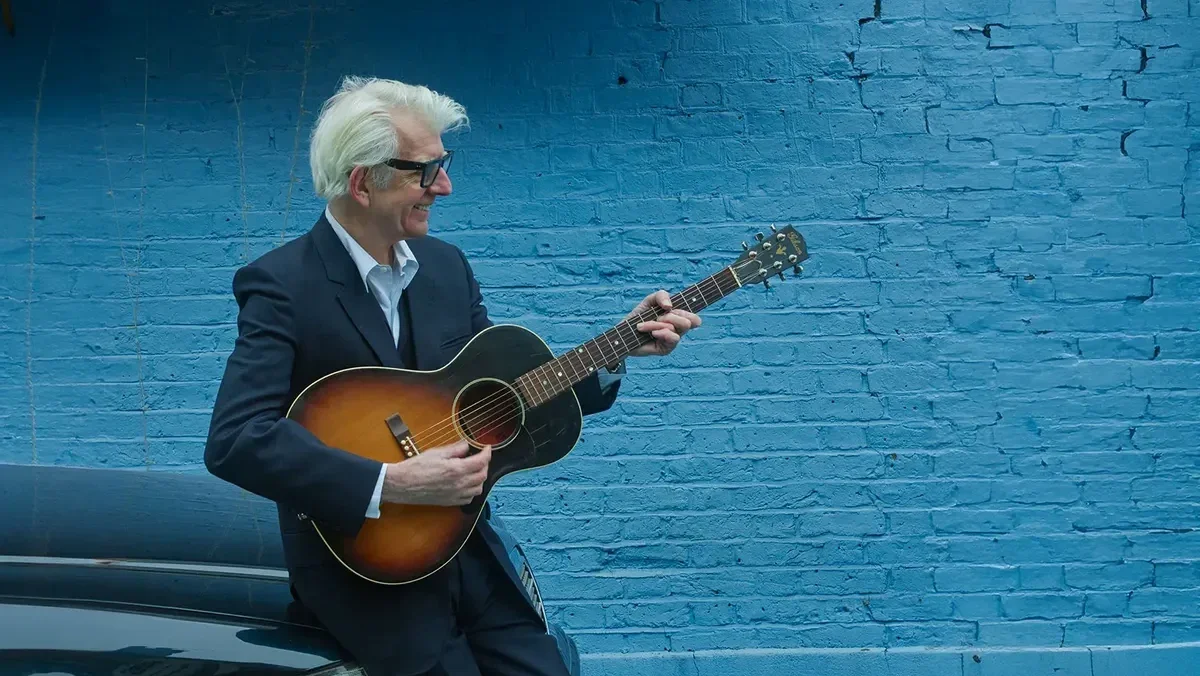

Butterfield and Bloomfield, the group’s great instrumentalists, own a lion’s share of the credit. Butterfield’s muscular, squawking harp playing sounds like a truck blowing through winter traffic at high speed on Chicago’s Lakeshore Drive. Bloomfield, meanwhile, might have been the ’60s first guitar god. His wild, manic lead lines and monster-sized tone were another prevailing force of nature within the band’s sound, capable of either elevating a song to more than it was or rendering it completely irrelevant.

That incandescent sound drew Dylan, who recruited Bloomfield to play lead guitar on “Like A Rolling Stone” and the rest of the “Highway 61 Revisited” album. After Newport, Bloomfield rejected the offer to tour with Dylan because he wanted to stay true to the blues and play with Butterfield.

Staying true wasn’t exactly in the cards though. The band’s next release, “East-West,” drifted from blues purism to embrace influences of pop and particularly, jazz and Indian classical music. The album’s long-form title track offers a paint-by-numbers template for the nascent psychedelic guitar jam. This was a record that certainly got a lot of play in the Haight-Asbury scene, and it wasn’t an accident that the Butterfield band soon decamped to the San Francisco area.

Eventually, Bloomfield left Butterfield in 1967 to write his own ticket and started a series of projects that were only really half-baked to begin with. As the ’60s continued, each quickly spiraled out of his control. He first formed the Electric Flag, a confederated, hodgepodge troupe whose music was a disorienting mix of American styles (blues, R&B, soul, etc.) and featured drummer Buddy Miles years before he’d make his name as a solo artist and sideman for Hendrix and Santana. After one record, Bloomfield left the group.

He then assembled a new backing group for Janis Joplin, but once again, quickly excused himself from the project once it was time to hit the road. A fruitful studio partnership with Al Kooper yielded a great album, “Super Sessions,” but Bloomfield once again wouldn’t or couldn’t follow through.

Meanwhile, the Butterfield band continued on with Bishop as the lead guitar player. By this time, however, the group’s star was clearly on the wane. The combo’s loyalist sound, clean-cut appearance and streetwise attitude was effectively eclipsed by all the West Coast rock groups. These acts were ultimately more attuned to pop-music hooks and folk-influenced lyrical narratives than Butterfield and they effectively stormed the charts and nudged the latter-day Butterfield band lower and lower on the bill at the Fillmore West and assorted festivals.

The Butterfield band eventually lost Bishop and the rest of the “East-West” lineup too. Their leader tried unsuccessfully to recast the group as horn band (a la the Electric Flag or Blood, Sweat and Tears). Butterfield even recruited a young David Sanborn to join on saxophone, but no career turnaround was possible. The group folded in the early ’70s and Butterfield’s prospects trailed off considerably throughout the ’70s until he was only playing small clubs.

For the group’s two most outstanding talents — Butterfield and Bloomfield — the final years of their lives were tragic and cruel. Bloomfield continued blowing through a series of aborted projects in the ’70s that squandered his considerable skills, between long periods in which he surrendered to his addictions. He died of a drug overdose under mysterious circumstances in 1981.

As for his former partner, Butterfield battled alcoholism and substance abuse for years before he too died of a drug overdose in 1987.

Of the original band, only Bishop, drummer Sam Lay and keyboardist Mark Naftalin are still alive to receive this belated recognition from the Hall of Fame. But, perhaps like the forgotten blues artists these guys championed and sought to reintroduce to the world so long ago, this new honor affords the Butterfield band one more chance to be remembered. New generations could hear their songs and come to realize how important their music proved to be.

What more could these students of blues music ask for than to be part of that tradition themselves?

Robert Johnson’s “Walkin’ Blues,” which was the lead track off “East-West,” offers the perfect summary of the band’s musical firepower thanks to Butterfield’s brilliant harmonica breaks as well as Bloomfield’s brilliant slide playing, choppy rhythm licks and unbridled solo. The song wasn’t a single, but was the closest these guys could get there and retain that authentic blues sound.