A major avian influenza epidemic struck the poultry industry in the midwestern U.S. over the spring and early summer of 2015. While it was primarily concentrated in the states of Iowa and Minnesota, multiple locations in Wisconsin were also affected, resulting in the destruction of nearly 2 million domestic birds.

Barron County, located in northwestern Wisconsin, is home to multiple turkey farms and a Jennie-O processing plant. Five flocks were struck with the disease there over April and May, as was one Jennie-O-affiliated turkey flock in neighboring Chippewa County — and industry and government agencies were quick to respond.

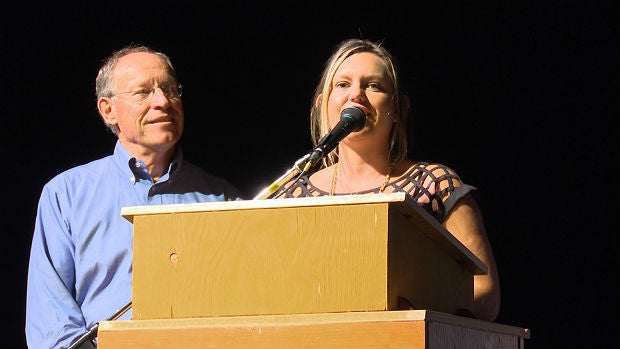

More than a month after the final quarantine was lifted, the epidemic was one of three topics discussed on July 31 at the Barron Area Community Center. It was the final stop of the Northern Lights Tour, a science education lecture series in five Wisconsin communities. Titled “The 2015 avian influenza outbreak,” this talk was delivered by Kelli Engen, a public health officer for Barron County, and Tim Jergenson, an agricultural agent for the UW-Extension Barron County. It was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s “University Place” program.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Key Facts:

- The U.S. poultry industry is largely based in the eastern half of the nation, with concentrations in the upper Midwest and several locations along the East Coast. Both the Mississippi and Atlantic migratory flyways cover these regions, and it’s thought wild waterfowl are a primary source of the disease. Wind and cross-contamination of manure and respiratory fluids are also believed to spread the virus.

- Symptoms of avian influenza in domestic poultry include: a lack of energy or appetite; swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattle and hocks; purple discoloration of the wattle, comb and legs; respiratory distress, including a runny nose, coughing and sneezing; stumbling and falling down; diarrhea; and, fairly regularly, sudden death without any clinical signs.

- Avian influenza was detected in a total of 10 Wisconsin farms. Five were commercial turkey operations in Barron County, one was a commercial turkey operation in Chippewa County, three were commercial chicken operations in Jefferson County, and one was a backyard flock in Juneau County. A total of 1,112,970 chickens were destroyed, as were 652,005 turkeys and 41,760 turkey hatching eggs. These numbers, of both farms and birds, were much smaller than those in Iowa and Minnesota, which were much harder hit by the epidemic. (Note: The numbers cited in this talk reflect early estimates of the sizes of the affected flocks. Officials at the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) issued final counts, which may differ from the numbers used at varying points during and immediately following the epidemic. Final DATCP numbers indicate that 1,348,306 chickens, 561,380 turkeys, 41,760 fertilized turkey eggs, and 33 mixed-breed fowl were lost in Wisconsin.)

- The poultry industry has an established protocol for handling avian influenza outbreaks of this type. After infection is confirmed, the farm is quarantined and the entire flock is depopulated inside the barn where the disease has been identified. After depopulation, the birds’ carcasses are mixed with wood chips and left inside the barn to compost over 30 days with a target temperature of 130 degrees Fahrenheit. After surveillance sampling confirms composting, the remains are removed and stacked on the premises of the farm, with the intention of landspreading it later as compost. The space is then disinfected, rested for 21 days or longer, and is then ready for restocking with poultry.

- There are thousands of backyard poultry flocks in Wisconsin. To prevent the spread of avian influenza, their owners are encouraged to keep their distance from affected areas and birds, maintain regular biosecurity practices (including cleaning and changing shoes), and avoid sharing equipment used with other flocks. If a sick bird is observed, it should be reported to the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection.

- While there is very low risk to humans of getting infected with the H5N2 variant of avian influenza responsible for this epidemic, public health officials in Wisconsin worked with the poultry industry to monitor employees and administer preventive doses of oseltamivir (known commercially as Tamiflu).

Key Statements:

- Jergenson on the number of birds depopulated: “Remember, I said there’s somewhere between 10,000 and maybe 15,000 birds in one building? If just one bird is sick, they depopulate the entire building. So, that’s why we get these really high numbers in the commercial industry… It doesn’t mean all those birds died of the disease. In fact, most of them were healthy, but they had been exposed to it, so depopulating was one method of control.”

- Jergenson on halting the spread of the disease by depopulation: “Research has show the most effective way to control the spread of avian influenza is by depopulating the birds inside these barns, and that’s the route that has been taken this season.”

- Jergenson on the poultry industry’s preparedness for the disease: “Avian influenza has been around before, so they had some idea of what the symptoms would be… We’d seen this disease cropping up in some of our neighboring states, so the industry was preparing for this and scouting for this disease all along.”

- Jergenson on the timing of the epidemic: “At this point, the working hypothesis is that this disease is being spread by migrating waterfowl beginning in the spring… Most of the detects were in April and early May in the Midwest, just at the time that waterfowl were migrating.”

- Jergenson on how hard the disease hit Wisconsin: “There have been 10 Wisconsin farms that have avian influenza detects during the spring and summer of 2015. Please understand, we have over 10,000 known registered poultry operations in Wisconsin. So while it’s devastating to have this disease on a particular farm, it’s still a very small percentage of the actual farms, poultry farms, that exist in Wisconsin.”

- Engen on assessing human exposure to the outbreak: “We needed to get a good idea of the employees from the industry where avian influenza was detected in our area…”

The slideshow for Engen and Jergenson’s presentation may be viewed here.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.