When Wisconsin lawmakers recently passed a bill that would triple the number of reading assessments young students receive, they cited low reading scores on national assessments and the tremendous gap between Black and white students’ scores.

“We are in such a crisis state in Wisconsin with our reading, we have to be doing something differently,” Rep. Joel Kitchens, R-Sturgeon Bay, told WPR’s “The Morning Show”. “This is not standardized testing, these are quick screens that take a minute or two that would be done multiple times a year so that we can identify these children that are struggling to read and put plans in place to get them reading.”

Gov. Tony Evers vetoed the bill last Friday. Still, it kicked up simmering concerns about Wisconsin students’ reading readiness, and about how accurately assessments measure that readiness.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

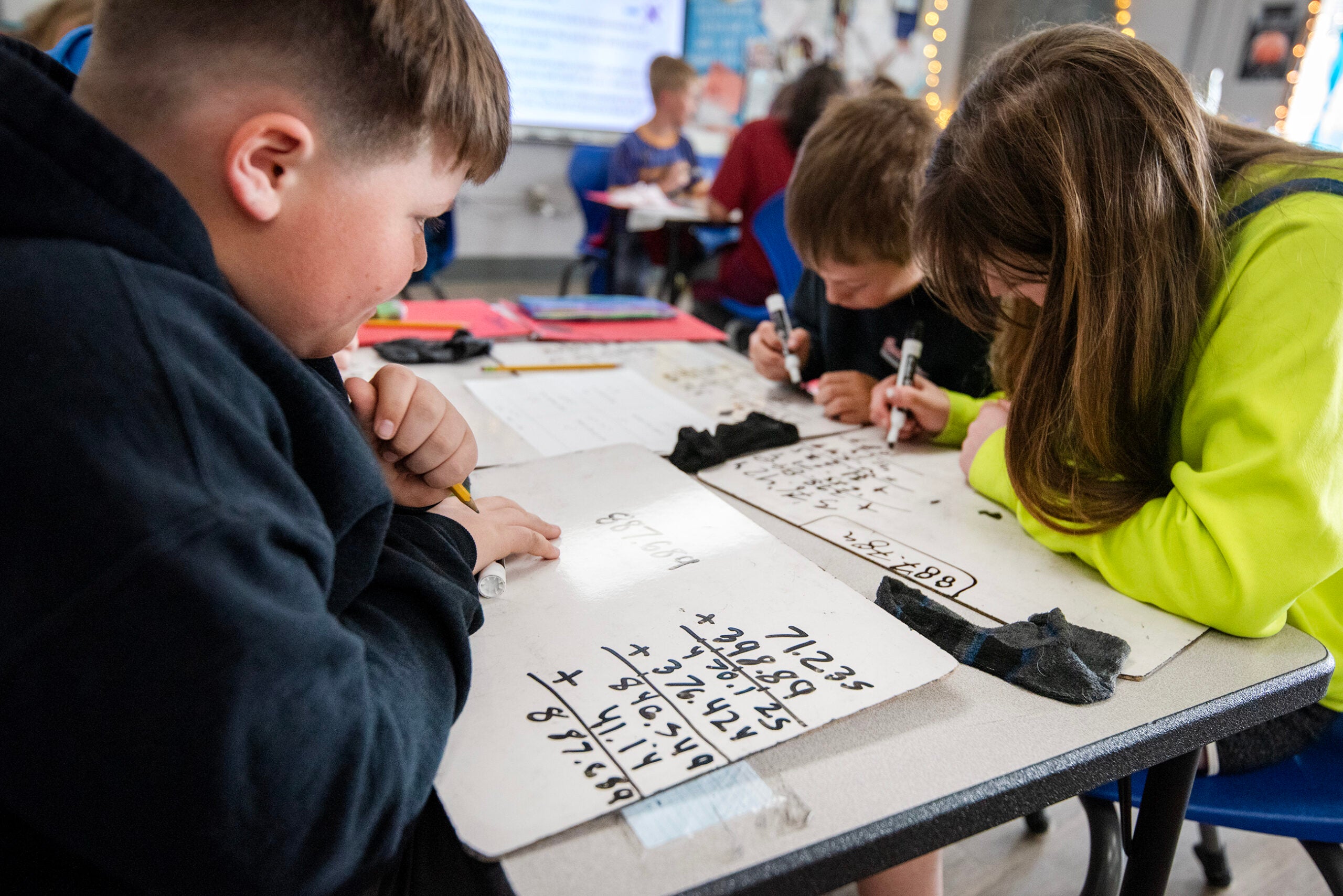

Darla Peanasky is the elementary curriculum and instruction coordinator for the Stevens Point Area School District. Like in other districts, Stevens Point students get a quick screening assessment at the beginning of the school year to figure out what skills students already have, and what they still need to work on.

“One of the things that I’ve really reiterated with my staff and my teachers is that, our screener, that’s one data point,” she said. “You need to pull in your classroom work, you need to pull in that historical data.”

That was even more true this year, said Peanasky, since school was remote for chunks of the last two school years due to COVID-19, and not every student was able to log on or retain information as easily in a virtual environment.

An emphasis on assessments might also miss students’ skills, said Mariana Pacheco, a professor of curriculum and instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who focuses on multilingual and English-language learning students and literacy. She said assessments — especially assessments at the beginning of a student’s time in school, in kindergarten or pre-K — can’t always capture what a student knows if their home language is Spanish, for example.

“They might have really rich and robust, exciting, engaging literacy and language practices in their home, but they might not be able to either demonstrate or articulate those basic skills (in those assessments),” she said.

Pacheco said assessing students when they just start attending school for the first time also runs into a general pitfall of academic testing, which shows up repeatedly in studies of the SAT and other standardized tests — they can be a better measure of what resources kids have at home than of kids’ academic abilities.

“It’s sort of an admission on the part of an educational system that you need to be ready — ready to learn, ready to read,” she said. “If you don’t come with those skills based on this reading readiness assessment … it’s an easier way to put it back on the students and on their families.”

School districts around Wisconsin are concerned about reading, and making sure their students are learning to read — especially after two disrupted school years.

The School District of Beloit started a new reading curriculum this year, in part with the help of federal COVID-19 relief funds to help address learning loss. It has built-in reading assessments as part of the curriculum that district executive director of teaching, learning and equity Theresa Morateck said would have met the assessment requirements under the vetoed bill.

“That’s very different from what we’ve done in the past,” said Morateck. “It’s explicit, it’s systematic in the way that students are learning how to read.”

Morateck said the school district’s old program was widely used across the state, and Beloit isn’t the only one to be rethinking how it teaches students to read. The new program is based in phonics — connecting letters to the sounds they make — as opposed to balanced literacy, which focuses more on comprehension and the meaning of texts.

Morateck said that while the new curriculum has been working well, it’s not enough to simply implement new teaching materials or assess kids more frequently.

“You also have to invest in your staff, and build their capacity to teach reading and to understand why the materials are designed or organized the way they are,” she said.

Similarly, to Peanasky, in Stevens Point, a bill adding more assessments won’t supply schools with what they need to help kids who are reading below grade level strengthen their literacy skills.

“We don’t need another assessment to tell us where our instructional and learning gaps are, we know that,” she said. “That’s one way you find out what kids need, but we need to be able to focus more on the instructional strategies and resources — that’s where you’re going to get more bang for your buck.”

Pacheco, the UW-Madison professor, was on a team that helped develop the reading framework and tests for the National Assessment of Educational Progress. She said the team worked to make the test more equitable, accounting for different experiences of language, literacy and culture.

“There was some pushback because it was perceived to be making the tests too easy, when in reality we’re trying to make the test more valid by accounting for some of this difference,” she said.

She said before Wisconsin adds more assessments, it’s important to think about what those assessments do — and don’t — measure.

“I think there should be a serious conversation about what the relationship should be between the assessments that we’re using and what we interpret them to mean, versus what’s actually happening in classrooms,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.