Predictions about the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle and the complexity of the phenomenon itself can easily create confusion about its impacts on weather and the economy in the U.S. and around the world.

Daniel Vimont, an associate professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, shared a sobering perspective about ENSO in a Sept. 4, 2015 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s “Here and Now” program.

In the interview, Vimont gave a rough overview of how ENSO works, how monitoring data can help farmers in southeast Asia endure the impacts of a strong El Niño pattern, and of why predicting its impact in Wisconsin and the broader Midwestern U.S. isn’t simple. He also spoke about why he finds ENSO so fascinating.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Vimont also points out in a recent Q&A with the Nelson Institute of Environmental Studies at UW-Madison, he doesn’t see El Niño, despite its undeniable power, as an entirely bad occurrence.

Key Facts:

- The 2015-16 El Niño is comparable to 1982-1983 and 1997-1998 El Niños, which were the strongest in recent history.

- El Niño’s weather impacts are most significant in the south Pacific and can include a delay of the monsoon season in Indonesia, which can have a big impact on that nation’s rice harvest.

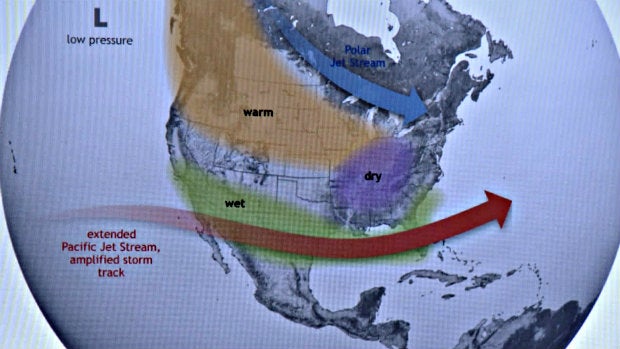

- El Niño periods generally are wetter in the southern U.S. and drier in the Pacific Northwest. This time around, Vimont said, the already very dry Pacific Northwest could be particularly susceptible to ENSO-driven drought conditions.

- The Midwest faces ENSO effects, but they won’t be the most pronounced in the U.S. Like many climatologists, Vimont hesitates to make strong predictions about the region.

- ENSO might not be completely predictable, but with proper monitoring, some effects are predictable enough that climatologists can work with economists and agriculture officials to mitigate how the phenomenon harms crops.

- Climate change doesn’t cause El Niño, but climate change can affect El Niño. That said, ENSO is so variable that it’s not always clear whether variations from one cycle to the next can be attributed to climate change.

- Research-funding issues have recently disrupted some ENSO monitoring in large stretches of the tropical Pacific Ocean.

Key Statements:

- On the impacts of seemingly small variations in ocean temperature: “It’s 2 to 3 degrees Celsius warmer than usual. That doesn’t seem like much, but you have to keep in mind that the Pacific Ocean is the biggest ocean basin in the entire globe. This (El Niño) involves a complete reorganization of the entire climate system in the Pacific,” he said.

- On one handy metaphor for understanding ENSO: “Think of El Niño like loading the dice. Any year may be wet or dry, but when an El Niño happens, the chances are it’s going to be a little more wet for California and so forth,” he said.

- On ENSO in the Midwest: “That loading-the-dice analogy? It’s not very loaded around here,” Vimont said.

- On whether ENSO-driven rains can help agriculture and relieve drought in places like California: “That’s good if that wetness comes as prolonged precipitation, but if it comes in torrential downpours, it’s not good for anyone,” he said.

- On the broader societal importance of monitoring ENSO conditions: “It’s critical that we can track the ongoing state of El Niño just so that we can help people prepare for it,” he said.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.