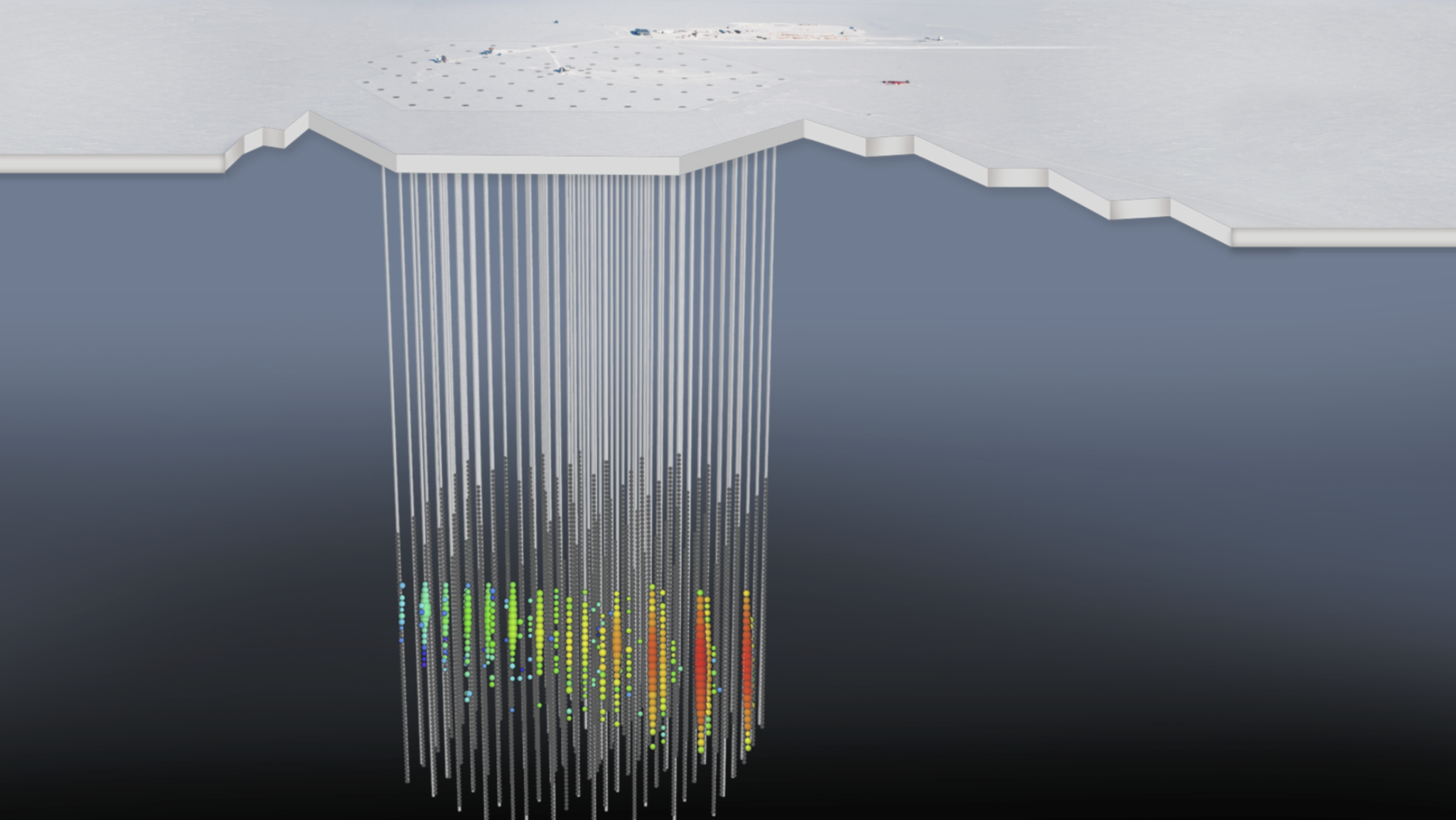

Scientists say a University of Wisconsin-Madison observatory about a mile below the South Pole played a major role in a breakthrough involving cosmic rays that’s being announced internationally Thursday.

High energy sub-atomic particles called neutrinos are associated with cosmic rays and continuously bombard the Earth. It’s been more that 100 years since Austrian physicist Victor Hess proved that charged particles in the atmosphere are coming from space. But scientists weren’t sure where in space they originate or what propels them.

Last September, UW-Madison’s IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica detected a neutrino crashing into the ice nearby.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

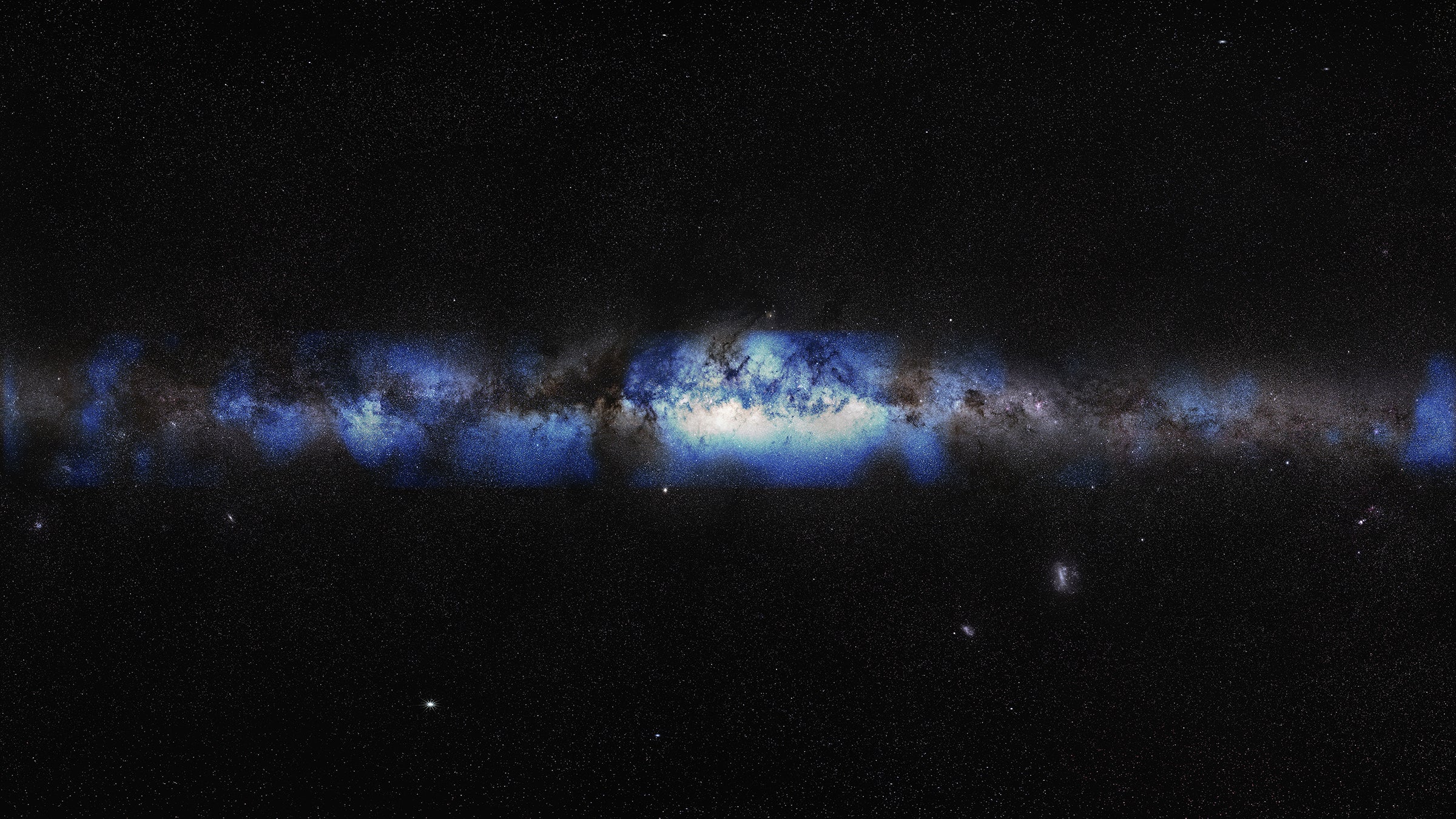

“Within 43 seconds, we sent the direction it came from, the precise direction, as a telegram to telescopes all over the Earth, and they detected a source,” explained UW-Madison physics professor Francis Halzen, lead scientist for the observatory.

Halzen said the source wound up being a blazar, a giant elliptical galaxy with a spinning black hole at its core. The galaxy is an estimated 4 billion light years from Earth. Astronomers have numbered it TXS 0506+056.

Following the detection, IceCube researchers looked at the detector’s archival data and found a flare of more than a dozen neutrinos from three years prior, from the same blazar. That helped confirm that the blazar is the first known accelerator of the neutrinos and cosmic rays.

Halzen said the discovery is important: “You know, this is not going to solve the energy crisis, or global warming. But in that context it’s a big deal, because first of all, we’ve solved the problem.”

Secondly, Halzen said, researchers with piles of data about cosmic rays or neutrinos will finally be able to study the physics of the cosmic accelerator.

Two papers published this week in the journal Science describe the discovery.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.