It’s estimated that more than 110,000 Wisconsinites are affected by Alzheimer’s disease, and that number is expected to grow significantly in the next 30 years. Additionally, studies have shown that African-Americans are twice as likely than Caucasians to develop the disease. This hour, we look at efforts in Wisconsin to raise awareness about the disease, especially in communities with a higher risk, and what’s being done to try and address the disparities.

Featured in this Show

-

Researcher Highlights Disparity Among African-American Alzheimer's Research

Alzheimer’s disease disproportionately affects African-Americans in the United States, but they are routinely overlooked in large-scale clinical trials studying the disease, says Dr. Carey Gleason, an associate professor of medicine focusing on geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

“A big part of that is the historical mistreatments by the research community where we have not approached research in a responsible way, and we have not included communities in decisions around research,” Gleason said. “Frankly, there’s been mistreatment.”

The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center is hosting the 8th Annual Solomon Carter Fuller Memory Screening event Friday, Feb. 16 an Saturday, Feb. 17 to celebrate Solomon Carter, the first African-American psychiatrist and pioneer of Alzheimer’s research. The event offers free educational workshops and memory screenings.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, African-Americans represent more than 20 percent of the 5.5 million Americans who have Alzheimer’s — they are twice as likely as Caucasians to develop the disease — but account for only 3 to 5 percent of clinical trial participants in National Institute of Health registered clinical trials.

Scientists believe the high rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s among African-Americans may be related in part to the prevalence of disorders that increase the risk of vascular disease, like diabetes and hypertension — conditions that are often associated with higher rates of poverty.

Gleason points to lifestyle factors as a major piece of understanding the correlation, and potentially fighting the disease. Preventing, or managing, risk factors like heart disease, high cholesterol, diabetes and hypertension in mid-life through diet, exercise and spiritual well-being could be key to lowering rates of the disease in the African-American community.

“The upside of this is we can do something about that,” she said. “We can’t do things to change genetics, but we can do a lot to change these lifestyle factors.”

However, it is still unknown precisely why African-Americans suffer from the disease more than whites, Gleason said.

In order to understand the disease on a person-to-person level, Gleason works to involve the community in her research from the beginning.

“Another part that is really important is this research should be done by people who look like the community,” she said. “The next generation of researchers have a stake in the disease because it’s affecting their community.”

The African-American community has long been skeptical of engaging in research because of a history of involuntary participation, said Theresa Sanders, co-chair of the Solomon Carter Fuller Planning Committee.

“In the African-American community … they were sort of thrown into this research process without their permission,” Sanders said. “It makes it difficult for African-Americans to hold their hands up and say, ‘I wanna do this,’ even if it may help their well-being.”

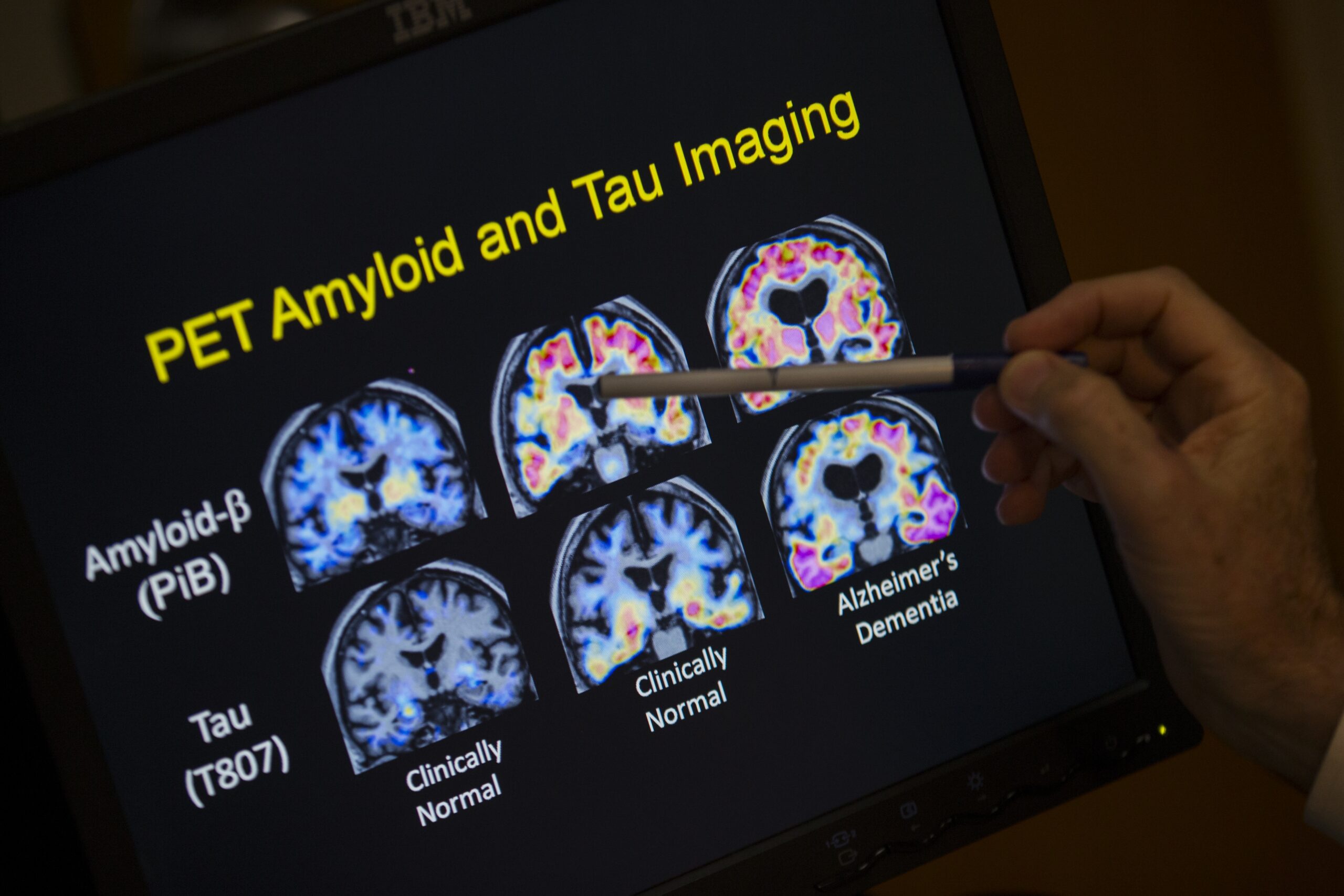

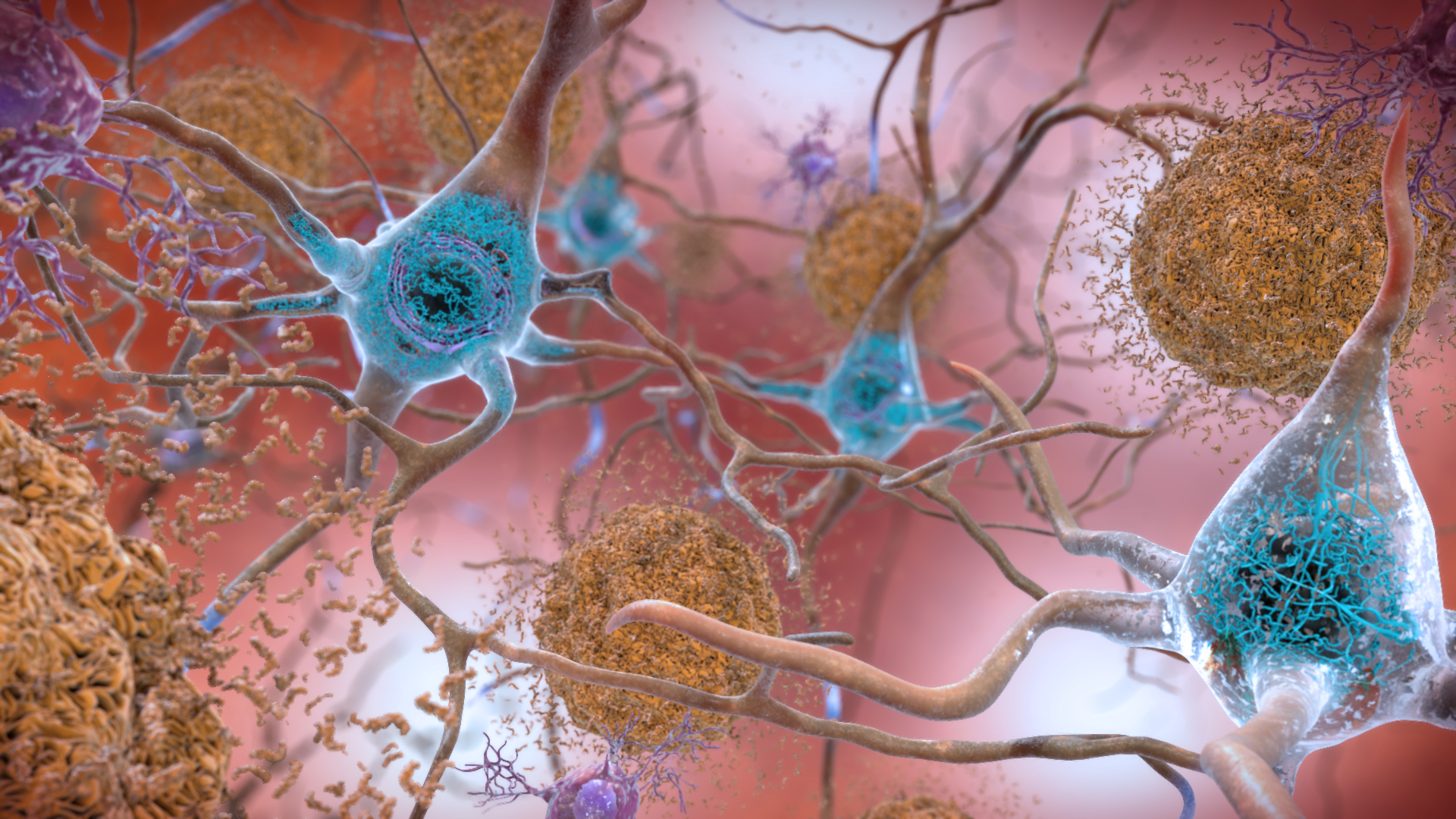

More than 110,000 Wisconsinites currently suffer from the progressive disease, characterized by deposits of abnormal proteins in the brain — and that rate is expected to grow exponentially in the coming decades, Gleason said.

“(The increase) is probably multiple issues,” Gleason said. “The first is that people are living longer, the second reason is that we’re getting better at recognizing it.”

Gleason urges those confronting the disease to not go it alone.

“That relationship is changing and your role is changing,” she said. “There is a lot of loss and grief, but … it helps to depersonalize it. This is the disease, this is not the person. It’s an evolving relationship and try as much as possible to find the joy in the new relationship.”

Episode Credits

- Kate Archer Kent Host

- Chris Malina Producer

- Carey Gleason Guest

- Theresa Sanders Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.