Renaissance man Ishmael Reed reflects on his prolific career. Also, crime maestro Megan Abbott gets to the “pointe” about her novel, “The Turnout,” which is set in the competitive world of ballet. And author/artist Kristen Radtke on the deep impacts of loneliness in America.

Featured in this Show

-

Renaissance Man Ishmael Reed Continues To Break New Ground

Ishmael Reed is a Renaissance man — a poet, novelist, essayist, songwriter, playwright and jazz pianist.

But he’s probably best known as a satirist. Reed often examines American politics and culture in such novels as “Mumbo Jumbo,” “The Terrible Twos” and “Conjugating Hindi.”

Reed has earned two nominations for the National Book Award and one for a Pulitzer Prize. He’s also received a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant.”

One of his most important innovations is Neo-HooDoo, in which Reed took the spirit of the African religion Vodun and combined it with contemporary issues in America. He writes in his manifesto that Neo-HooDoo “believes that every man is an artist and every artist is a priest.”

As Julian Lucas wrote in his “New Yorker” profile of Reed:

“He called it ‘Neo-HooDoo.’ A postmodern amalgam of jazz, vaudeville, Haitian vodun, ancient-Egyptian mythology, and Southern conjure, it was Reed’s campaign to rejuvenate a narrowly Westernized America. The ‘secular’ hierarchies of artistic merit, he suggested, were not only racist but secretly theological — and there were no savvier heretics than the enslaved Africans who had concealed their gods in the full-body ecstasies of Christian worship. Their successors were Black entertainers like Josephine Baker and Cab Calloway, whose charisma had done so much to desegregate American tastes. Reed saw his own role as storming the West’s literary inner sanctum. ‘Shake hands now/and come out conjuring,’ he wrote in a poem of the time. ‘May the best church win.’

Reed’s movement was pluralistic in every sense: international, cross-genre, collaborative, and capacious enough to elude definition. His ‘Neo-HooDoo Manifesto’ (1969) encompasses everything from the ‘strange and beautiful fits’ that the Black slave Tituba gave the children of Salem’ to ‘the music of James Brown without the lyrics and ads for Black Capitalism.’ Though Reed looked abroad for inspiration — especially to Haiti, whose traditions he encountered in the paintings of Joe Overstreet and the writings of Zora Neale Hurston — the manifesto resolutely centers on Black American life. Neo-HooDoo never been to France. Neo-HooDoo is ‘your Mama.’”

“And so in the 1960s, Black writers departed from imitation,” Reed told WPR’s “BETA.” “For example, James Baldwin was influenced by Henry James to the extent that he wrote a critical piece about Henry James’ work. And Henry James’ son sent him a portrait of his father. Of course, Henry James was a wannabe Anglo because I think he tried to smother his Irish background, a terrible anti-Semite at the same time.”

Reed said that Ralph Ellison is indebted to Ernest Hemingway and T.S. Eliot; however, Reed did not find anything in “The Invisible Man” that contains traces of either. Reed suspects that Ellison felt he had to say that “in order to gain admission to the club at the time.”

In the 1960s, Black writers broke with that, turning to their own culture and history.

“They began to study Arabic, the indigenous African languages,” Reed explained. “I went to something called Black folklore — using that and trying to put a postmodernist bent or slant on Black folklore.”

“And people went into other different directions, trying to find something that was more connected to their roots,” he continued. “Amiri Baraka was a genius at that because he, you know, abandoned his so-called ‘eloquence of language’ and wrote in the style of the street talk.”

In 2019, Reed’s play “The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda” made its debut at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe in New York City. As the title indicates, the play is a response to Miranda’s hit musical, “Hamilton.”

Reed’s play is a critique of “Hamilton,” offering a fictional version of the musical where creator Miranda is visited by apparitions of slaves, Native Americans and enslaved servants. The New York Times described it as “a cross between ‘A Christmas Carol’ and a trial at the Hague’s International Criminal Court.”

“I thought that the presentation of Alexander Hamilton on Broadway didn’t square with my research,” Reed said. “And I think actually, although I got a lot of criticism for the play by those who were ‘Hamilton’ fans — Hamilfans, they call themselves — the discussion was begun by three women historians: Lyra Monteiro, Nancy Isenberg, and Michelle DuRoss, especially Michelle DuRoss.”

“She takes on those historians who put out the myth that Hamilton was some kind of abolitionist, one by one,” Reed continued. “I said it reminded me of George Foreman on the afternoon that he fought five opponents at one time. You know, it’s devastating. And so the point of the play was that although it was criticized by people who had seen it, especially on ‘Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!‘ on NPR. It was subjected to ridicule even though they hadn’t seen the play.”

The moment of “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me” Reed is referencing begins at 8:48 in the clip below.

Reed explained that even though Miranda used Ron Chernow’s biography, “Alexander Hamilton,” as the basis for his play, Miranda could have consulted other sources. Reed points to the New York Times story which revealed evidence that Hamilton bought, sold and owned slaves.

“So I thought that I would respond to this billion-dollar production with a rebuttal,” Reed said.

Reed also talked about Hamilton’s writings in which he ranked Black people with cattle and horses, like farm property.

“Both he and Washington believed that Native Americans should be exterminated. And I ran across a letter that Hamilton wrote where he congratulated the vigilante mob for massacring a Native American village,” he said.

“So they have a billion-dollar enterprise going on here. I think we spent about $50,000. So it’s a real David versus Goliath conflict. And when (Disney’s film adaptation of ‘Hamilton’) happened, we followed them all over the world, or Europe, China, all over.” Reed said.

Reed is part of the longest continuing series of music poetry collaborations, the Conjure projects. Many of Reed’s poems and lyrics are set to music by great musicians likeTaj Mahal and Allen Toussaint. One of the poems is called “When I Die, I Will Go to Jazz.”

Reed said the poem is a response to Ted Joans’ famous poem, “Jazz Is My Religion.”

“I was replying to Ted Joans, whose famous poem is ‘Jazz Is My Religion.’ And if you go to YouTube and you can find that poem, I tried to duplicate the rhythms of jazz on the page,” he said. “It’s got to sit like a metaphysical question, whether you want to go to paradise or whether you want to go to a place where there’s like a thousand years of jam sessions. This poem is read at funerals.”

One of Reed’s favorite versions of his words turned into music is Toussaint’s rendition of “Skydiving.”

“That was really a poem that was very therapeutic for me. I was going through a difficult, dark time and that poem rescued me from that despair,” he said.

Over the course of his 50-year career, Reed has displayed an uncanny ability to predict the future. So what does he think the future holds for Planet Earth?

“Well, I see nothing but pessimism. There just seems to be an inability to grasp the peril that the Earth is in. I mean, of course, the Earth will continue for, you know, maybe another billion years. But it may not continue with this species, and I’m just wondering, Is there some kind of death wish in our DNA that would have this happen?“

“And so my new story I’m writing, it ends with one of the characters speculating about the future of the Earth. The character talks about the U.N. report that talks about approaching the point of no return. And the character says, ‘Well, the problem with the report is that most of the leaders of the world can’t read this. It’s going to leadership that’s just taking the world to ruin.’”

-

Crime Novelist Megan Abbott Remains On Pointe With 'The Turnout'

If you’re familiar with the works of crime novelist Megan Abbott, you’re aware of her ability to mine the thrill out of nearly every scenario. She’s delivered drama in the world of higher learning with her previous novel, “Give Me Your Hand” and created teenage tension in the world of cheerleading with her hit novel and subsequent TV series, “Dare Me.”

Now, she’s dancing with her lifelong love and fascination with the world of ballet in her novel, “The Turnout.”

“I had always imagined that one day I’d write about (ballet). It just is a world that’s always fascinated me,” Abbott told WPR’s “BETA.” “I was one of those girls that tried to take ballet class and sort of failed miserably. But the sort of enchantment of the ballet stuck with me. And it’s sort of the exotic nature of that life.”

Abbott’s fascination with ballet never really dimmed, but it was re-framed recently when she re-read “Dancing on My Grave,” the memoir of world-famous ballerina, Gelsey Kirkland. She admits to connecting with the painful realization plaguing Kirkland of attempting to achieve relentless perfectionism.

“I was thinking about why I connect to ballet and why many women do. And there is this notion in ballet of how you’re supposed to be this sort of ethereal being, this sort of graceful creature that glides across the stage,” Abbott said. “You start to think about that in relation to women in general. There’s a facade that a woman is supposed to always put on and she’s never supposed to let them see her sweat and to be able to take on everything and to sort of be the people pleaser and the achiever. And I think so many women get caught up in that. I know I have. And so there’s a sort of tyranny in it.”

Abbott based the idea for her story and her main protagonists — sisters Dara and Marie Durant — on her own childhood ballet class and teachers. The Durants are orphaned early in life and inherit their family home and their mother’s ballet studio.

“The studio I attended was run by these two sisters, and they’re very different from the sisters in ‘The Turnout,’ but we just imagined all kinds of romantic and interesting possibilities for them as we sort of stood in class and tried to do our moves,” she said. “So, I started to think about what it would be like for two sisters who run a school together and it sort of came from there.”

Abbott blended that concept with another. While listening to the true-crime podcast “Dirty John” about a manipulative serial predator conning a woman and her family, Abbott was struck by the reaction of the women in the comments section.

“They always say never read the comments section, but I was really, really intrigued by all this anger that I saw directed not at the serial predator, who in fact is a murderer, but at the women who fell for him,” Abbott said. “And it was very angry. That ‘How could you be so stupid?’”

“I really wanted to explore that dynamic in the novel,” Abbott said. “To have one of the sisters, the older one Dara, be very judgmental of her younger sister Marie’s romantic choices and try to figure out what that’s like from the inside, how might one come to feel that way and why.”

That disruption comes in the form of Derek, a contractor who is hired to retrofit and remodel the Durants’ studio after a suspicious fire. He drives a wedge between Marie, Dara and Charlie — Dara’s husband who also happens to be her mother’s former star pupil. Derek’s manipulation of Marie threatens to uncover the sister’s salacious past.

“For Dara and Marie and Charlie, it’s been so extreme in their case as they’ve lived in their family home for their whole lives and worked in their family’s studios, they really had these twin castles that they moved between. And so, these roles and rituals and insularity has become stifling, and something’s got to break.”

Derek’s remodel and budding romance with Marie is all set against the clicking tock of the Durant sisters annual presentation of “The Nutcracker.” Abbott chose “The Nutcracker” because Tchaikovsky’s ballet adaption is so ubiquitous. However, she also points out it is an important production to nearly every ballet studio in the country, not just for ticket sales, but as a recruitment tool to other young potential clients.

“All those little girls, like me, who sit in the audience for one year’s ‘Nutcracker’ and then want to take ballet classes, and they can be on stage the next Christmas,” Abbott said.

But, the story of “The Nutcracker” by E.T.A. Hoffmann carries an eerie parallel Abbott attached to as well.

“It turned out to be so perfect and sort of unfold all these other resonances because it really is a female coming-of-age story,” Abbott said. “There are darker elements of ‘The Nutcracker,’ too. I read the original story and was able to tease out some of that, too. The E.T.A. Hoffmann story is really a kind of dark, and I’d say a very Freudian fairy tale.”

Similar to her hit television adaptation of “Dare Me,” Abbott has plans to adapt “The Turnout.” She says television has hit a peak for adapting novels into limited series without asking audience to commit to binging multiple seasons. For her part, Abbott was prepared out of the gate for this approach.

“It was really weird because usually I’ve had a year or so after the book comes out that I have adapted some of them,” she said. “And this time it was right after I finished the book that we sold it to the studio. And so, I had to sort of think about it differently, very quickly. In some ways it was easier because it hadn’t set in my head as long. You can start to think about it visually and think about the visual storytelling.”

-

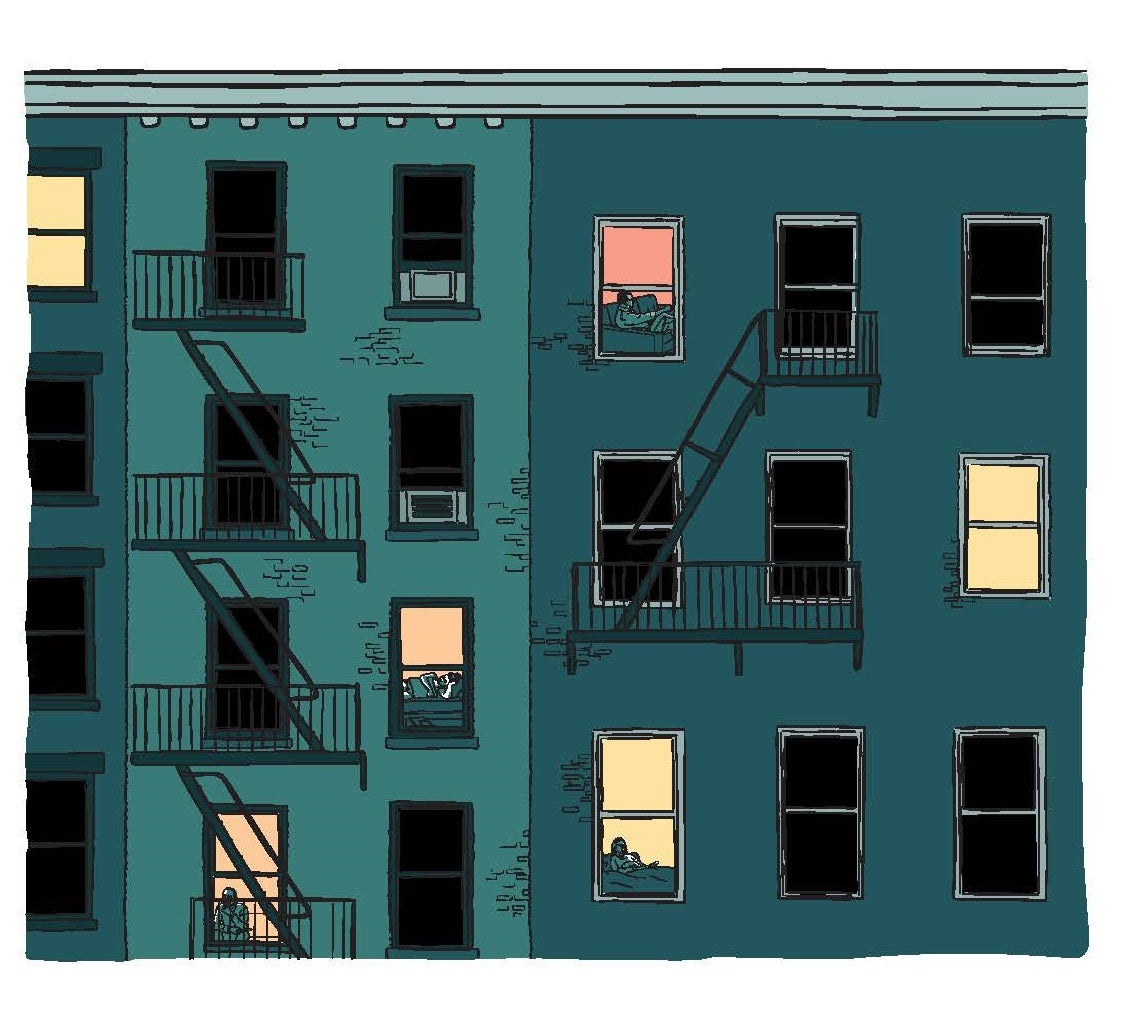

Author, Artist Kristen Radtke Explores Loneliness In Graphic Detail

In “Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness,” Kristen Radtke combines evocative artwork with intimate and thoughtful prose to create a comprehensive cultural history of loneliness in the United States. She explores loneliness through a variety of different lenses, including gender, violence, technology and art. Radtke explains how loneliness is part of the human condition and how it can be hazardous to our health, among many other fascinating facts. “I can’t really remember the moment that I became interested in loneliness,” Radtke told WPR’s “BETA.” “I just became slowly obsessed. I started writing about loneliness in 2016, which I think was a lonely year for a lot of people. And through my research later, I learned that loneliness traditionally spikes at three ages — your late 20s, your mid 50s and your 80s. And I was in my late 20s. So it was sort of at this moment of transition. And I think I was just thinking about isolation and then kind of accidentally started researching and studying it.”

The title “Seek You” comes from ham radio. As Radtke learned in adulthood, her father was very interested in ham radio when he was child.

“And when you make a call on amateur radio, either using your voice or using Morse code, you make what is called a CQ call, the letters C and Q, and that just means you’re kind of reaching out to anyone who’s there,” Radtke explained.

Radtke said it’s too early to tell how the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 affected her work on “Seek You.” She said that a massive imposed isolation where everyone was under the same guidelines is different from the concerns of chronic loneliness.

“I think it was easier for us to talk about because we were really all in the same boat. But in a regular year, I think we don’t talk often about loneliness because it feels shameful or personal and the pandemic really destigmatized loneliness. I think it remains to be seen whether or not that will continue to be the way that we look at loneliness or not,” she said.

Radtke grew up in rural Wisconsin and moved to Brooklyn, New York in 2014, after a two-year stint in Louisville. But she says her loneliness started before the cross-country move.

Radtke described herself as “a pretty lonely kid.” And said she thinks a lot of children are lonely in their pursuit to determine their place in the world and what their life is going to look like.

“I’d always kind of loved cities and I always gravitated toward cities. And I really like Wisconsin, I come back and visit a lot. But I think it didn’t feel like a jarring transition. I think any time anyone moves, there is kind of that period where you’re trying to get your feet on the ground. And when I interviewed people for this book about loneliness, a lot of people cited a move, like a geographical move, as one of their loneliest moments,” she said.

But Radtke says there’s a big difference between aloneness and loneliness.

“Someone can spend a lot of time alone and never feel lonely and someone can be in very crowded spaces all the time and feel alone,” she explained. “Every single person has a built-in biological threshold for how much loneliness or aloneness that they can tolerate. And so certain people are more predisposed to loneliness than others, which is why a lot of people can live alone and feel completely content and why someone else maybe needs to have a lot more interaction.”

In her book, Radtke refers to a 2017 study that found that people who lived by themselves were 32 percent more likely to have died within a seven-year period than people who lived with others.

“It’s one of the things that I didn’t expect to learn when I began this book. But it was startling,” she said. “So our bodies are actually just less effective when we’re feeling disconnected.”

[[{“fid”:”1563926″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3EGraphic%20courtesy%20of%20Kristen%20Radtke%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3EGraphic%20courtesy%20of%20Kristen%20Radtke%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””,”title”:”Page 131 of Kristen Radtke’s book, \”Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness.\””,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

Radtke also writes about the relationship between media coverage and loneliness. She explores television’s portrayal of male protagonists like “Mad Men’s” Don Draper and “The Wire’s” Jimmy McNulty.

“I see those characters as just renditions of cowboys,” she said. “The cowboy myth is a huge part of American ideology. And it’s all predicated on the idea of being alone, like it’s a man who rides off into the sunset by himself. And there’s something very alluring about that character.”

“I think that it’s also wrapped up in ideas of American individualism, which I think are equally dangerous. But it sort of creates this character that isn’t entirely realistic,” she continued. “But it also prizes individualism and isolation in sort of an alluring, attractive way that I think is a little bit dangerous to the way that we should actually relate to one another.”

In her 2017 book, “The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone,” Olivia Lang made the case that loneliness can be a gift.

And Radtke agrees.

“I think that loneliness is important; it’s essential,” she said. “Loneliness has a very important biological purpose, which is that when we feel alone, we feel threatened. And we need to reach out to another person. And that’s really important.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Ishmael Reed Guest

- Megan Abbott Guest

- Kristen Radtke Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.