“I like that Barack got that job, it’s a cool job…I like how he got it. You can’t do what he did in real life. You’re like, to already have a good job, like you know what, ‘I’m gonna take every day off this job while I look for a better job.’ ‘How many days you want off, Barack?’ ‘Every day for the next two years. And guess what, if I don’t get this job, I’m still coming back to this job to finish the shit up.’ You can’t do that in real life. You’re working at Subway. ‘Man, I’m tired of workin’ at Subway. I’m gonna take every day off and see if I can get a job at Quizno’s. I heard Quizno’s has benefits.’ They don’t. Stay your ass at Subway. Don’t burn bridges.”

Comedian Hannibal Buress summed up Barack Obama’s rapid ascent from a junior U.S. Senate seat to the presidency with a bit about hopping jobs between sandwich shops. This being stand-up, there’s a bit of hyperbole involved — it’s not as if Obama never showed up to work at the Senate when he was running for president.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But elected officials looking to get re-elected or climb the political ladder or have a degree of leeway to devote time to what’s essentially a job search that most other public employees and private-sector workers don’t.

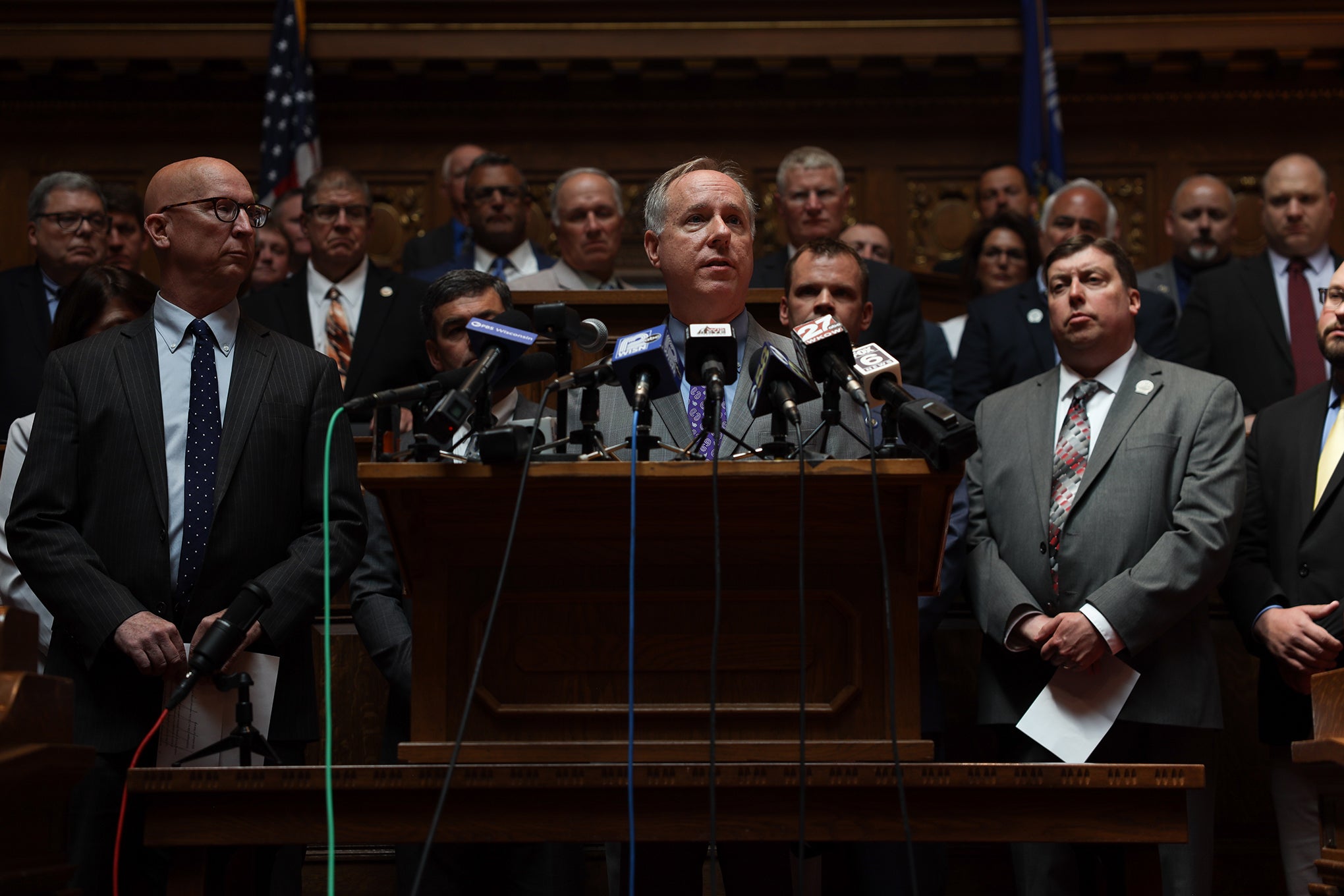

Both of the major party candidates running for governor of Wisconsin are doing so while holding down elected posts enshrined in the state constitution. Both are also full-time jobs that pay substantial salaries. Scott Walker, a Republican, is seeking a third term as governor and draws a salary of $146,786 per year. Tony Evers, a Democrat, is in his third term as the state superintendent of public instruction, where he earns $122,096 per year. They’re each high-profile and high-responsibility jobs. That said, so too is running for statewide office, particularly in an historic election year.

But where does the state’s time end and the campaign’s time begin? Do Evers and Walker have to burn vacation or other paid time off when they’re campaigning on a weekday?

Not exactly. While they can take vacations from their executive-branch jobs, their paid time off doesn’t work quite the same way as that of other public employees, and the rules surrounding their political activities give them flexibility in day-to-day activities. And state legislators operate under much the same conditions. State law (230.35(1r)) entitles elected officials to take vacation time “without loss of pay,” but also indicates that, unlike many other state employees, elected officials can’t cash out unused vacation time when they leave their jobs.

At the same time, state and federal laws forbid government employees from using public resources for political purposes. For example, the federal Hatch Act places numerous restrictions on political activity among most federal employees, and some at lower levels of government whose staffers work on federally funded programs. In just about any situation, it would be illegal for a government official or rank-and-file public employee to do campaign work using, say, a state-issued vehicle, laptop or mobile device.

But Wisconsin has seen multiple examples of public employees running afoul of these requirements over the past couple of decades.

Walker faced investigations over his tenure as Milwaukee County executive, when county staff did campaign work on government time; several aides were convicted, though Walker was never charged with a crime. More recently, Walker and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, have faced scrutiny for using state-funded airplanes in circumstances that critics say appear to blur the line between governing and campaigning.

In 2009, Evers paid the state a $250 fine over an incident in which he solicited campaign donations while on the job as deputy superintendent, emailing another education official’s government account in an effort to set up a fundraiser event.

Going a bit farther back, the “caucus scandal” of the early 2000s broke when state legislators were caught conspiring to run campaign activities on state time; this culminated in legislators from both parties being convicted of crimes, and prompted the state to impose new restrictions on legislative staff’s political activities.

“You can’t use public resources to run, and so there has to be some separation,” said Reid Magney, a spokesman for the Wisconsin Elections Commission. “The term of art is ‘use of office.’”

The state and campaign offices of Evers and Walker both voice a commitment to obeying laws around campaigning and preventing the abuse of state resources. However, neither camp would answer specific questions about how they go about interpreting and implementing rules that draw lines between state time and campaign time for candidates with busy, full-time public jobs.

“The campaign follows all laws and proper procedures in ensuring that we do not use state resources for campaign purposes,” said Walker campaign spokesman Austin Altenburg.

“We have protocols in place to ensure no state resources are used for campaign purposes,” said Amy Hasenberg, a spokeswoman working in the governor’s office.

State Department of Public Instruction spokesman Tom McCarthy noted that while Evers doesn’t literally punch a clock, he’s fully committed to his day job. “Obviously he’s still punching the clock here at the department and working here, and working another job too, which is running for office,” McCarthy said.

Maggie Gau, Evers’ campaign manager, said through a spokesperson that the superintendent’s “campaign follows all applicable laws governing the separation of official and campaign duties.”

None of these answers quite explain how the candidates divide up one particular state resource — their time — between their dual roles.

Different rules for officials and staff

Articles 12 and 13 of the Wisconsin Constitution, and section 16.147 of state statutes, set out restrictions that generally forbid elected officials in one office from simultaneously holding other offices or “dual employment” in government. In section 12.03 of state statutes, the law places limits on when and where candidates may “engage in electioneering,” like restrictions on campaigning near a polling place on election day. Additionally, the so-called “50 piece rule” (section 11.1205), which, confusingly, is often also called the “49 piece rule,” limits the amount of mailings a state or local elected official can send with public funds when they’re up for re-election or running for another office.

State law also prohibits using state or local government vehicles on the campaign trail “unless use of the vehicle or aircraft is required for purposes of security protection provided by the state or local governmental unit,” and forbids soliciting campaign donations from state employees during working hours.

Guidelines for University of Wisconsin System employees direct employees who want to run for office to talk with their department chairs and take a leave of absence or have their appointments reduced if campaigning will interfere with their work. As for civil servants, state law (230.40) clearly requires that they take a leave of absence if running for public office.

But elected officials are not civil servants, and the law allows them a more fluid relationship between campaign time and time on the taxpayer’s clock.

Take one of the more time-consuming aspects of any campaign: fundraising. It is illegal to solicit campaign contributions in a state office building during working hours. For instance, state ethics guidelines clearly state that campaigns, not the state, should pay for campaign-related phone calls. But this rule doesn’t preclude a legislator or governor, say, from ducking out of the office and taking a quick walk around the Capitol for a fundraising call on a campaign phone and line.

The guidelines are much more strict for legislative staff. State ethics guidelines also tell staff to keep campaign work away from the Capitol and state offices, report their paid time on this work to legislative officials, and use evenings, weekends, lunch hours or other time off from their legislative day jobs for those activities. They can use vacation time to work on a campaign, but not comp time.

There are, of course, ethics laws that apply to legislators themselves — for example, rules forbidding a legislator from selling their vote on a bill for a campaign contribution — but few that seem to dictate how they divide their time between campaigning and official government work.

“As far as their time, legislators are always 24/7,” said Jeff Renk, chief clerk of the state Senate. “They can work as little as they want or as much as they want … They just can’t do anything campaign-related in their office or using state resources. That’s always in place that they cannot do that. But unlike a staffer, when they leave the office, they’re on their own time.”

Loose rules, deeper issues

Wisconsin has a full-time state legislature, but that doesn’t mean legislators have to treat their posts as full-time jobs, said Mordecai Lee, a former Democratic state legislator and current professor of urban planning at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. While law forbids various blatant abuses of office for political purpose, there’s also a generally accepted understanding that an elected official’s work is always political.

“There’s a blurring of governmental and political activities and motivations,” Lee said.

Unlike people in government staff jobs, elected officials aren’t punching clocks or filling out a timesheet for a supervisor or HR person to approve. There generally are not rules requiring elected officials to spend a certain amount of time per week on actual government business, Lee said. That leaves it up to voters, the press, public-interest watchdog groups, and other organs of government accountability to determine whether or not legislators and elected executive-branch officials are working hard enough at their duties.

Lee argues that this standard isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it means people involved in American politics are self-starters. He cited the example of John F. Kennedy, who ran for President as a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts. Kennedy had a “lousy attendance record” in the Senate during his presidential campaign in 1959 and 1960, Lee admits, but did that necessarily mean American government or society were worse off?

“It’s hard to make that argument,” Lee said. “We want ambitious people running for higher office.”

For Jay Heck, executive director of the advocacy group Common Cause Wisconsin, these blurred lines illustrate how politicians in Wisconsin have too much power and privilege, and that having a full-time legislature doesn’t serve the state’s best interests.

“There’s no specific rule that says that they have to report the time they spend campaigning versus official business,” Heck said. “There are not really rules that designate what legislators have to do.”

Because there’s no specific tracking of how legislators and other elected state officials divide their time between campaigning and state business, it’s hard to know who abuses that fluidity and how much, Heck said. To further complicate matters, while posts like governor, attorney general, and state superintendent are generally treated as full-time jobs unto themselves, legislators can still hold down other jobs while drawing their full-time legislative salaries. They can also claim a government-funded per diem whenever they stop in at their Capitol or district offices, even if it’s just to spend a few minutes answering emails, he added.

Heck said such privileges undermine the notion that legislators are above all public servants, and can set taxpayers up to unwittingly subsidize campaign activities.

“One of the problems is that while legislators do not raise money, for instance, from their office phones, because that would be using state property, there’s nothing to stop a legislator from going outside and using their cell phone to raise money for their campaign, even in the course of a day when they’re in Madison and the legislature is in session or out, so there’s really no parameters,” Heck said. “There’s a certain amount of quote-unquote honor system.”

When officeholders don’t stick around

Another type of honor system is a candidate’s commitment to the office they’re seeking — voters don’t know for sure how long an officeholder will stay in a given post if elected. A state legislator might leave to take a state cabinet post or a private-sector job, for example, and any elected official is liable to seek higher office.

During his 2014 campaign for a second term, amid rising speculation that he wanted to run for president, Walker initially dodged questions about whether he’d commit to serving out that term if re-elected. But in an October 2014 debate, he made an explicit promise about the matter: “My plan if the people of the state of Wisconsin elect me on November 4 is to be here for four years. Tonette and I had to work pretty hard three times now in the past four years to run for governor. It’s a position I’m committed to.”

Walker reneged on that commitment when he announced a presidential run the following summer. He dropped out of the race after 10 weeks.

Speculation continues, given Walker’s political ambitions, including future presidential runs or the potential for federal Cabinet posts. In a September 2018 Politico story, Walker challenged a reporter who asked if the people of the state could trust him to serve out a third term in full.

“Tony Evers ran for superintendent for a four-year term and a year after, he’s running for governor. You ask him the same question?,” Walker asked. “That’s on the record, right? You’re going to ask him the same question?” (Politico indicated it subsequently posed that question to Evers, and received a ‘yes’ in reply.)

After that interjection, Walker assured that he would serve a full third-term, saying, “I’m committed to being governor.”

As this exchange demonstrates, an ambitious politician can face fallout for, as it were, trying to move from Subway to Quiznos.

What Keeps Walker And Evers From Campaigning On The Clock? was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.