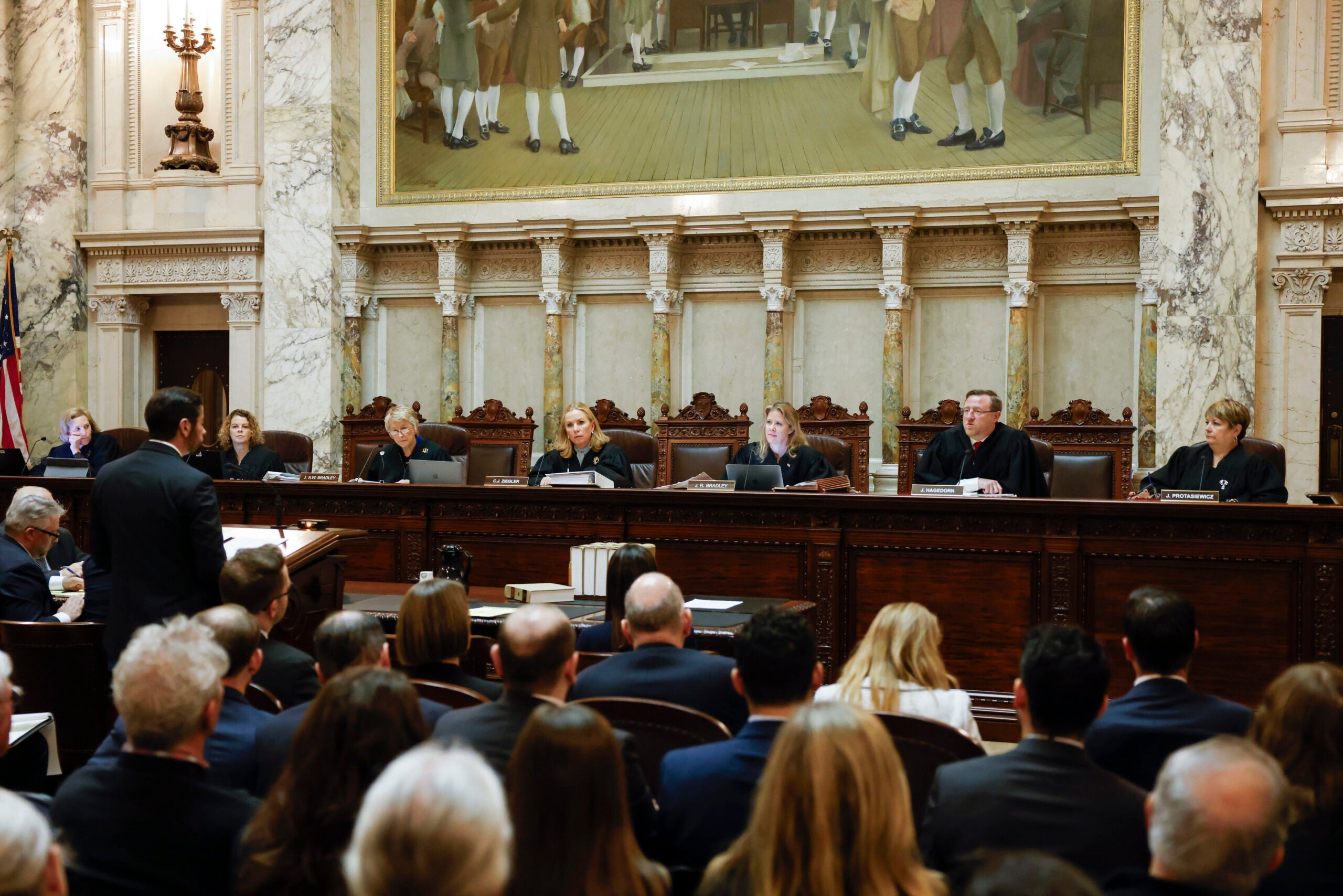

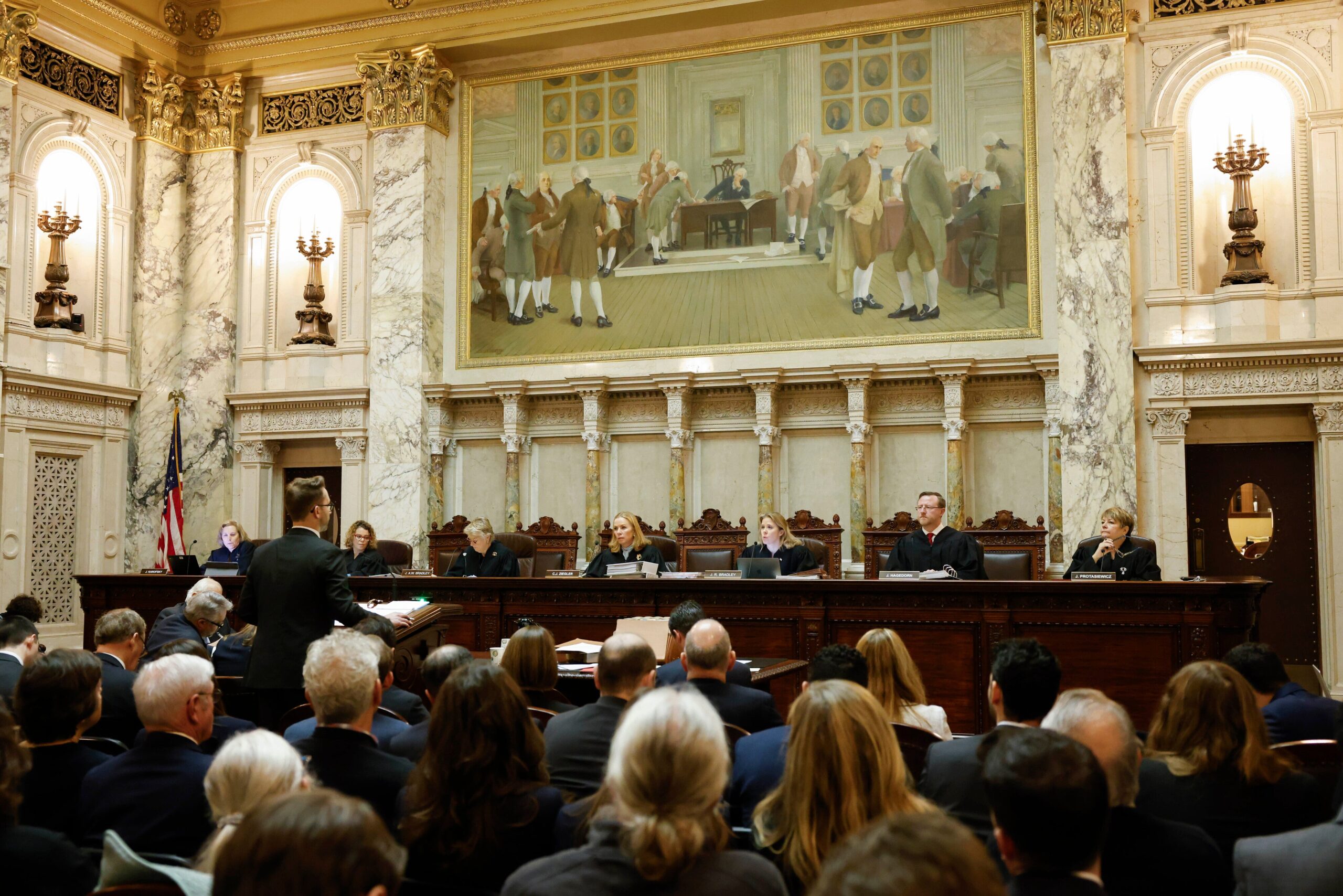

The Wisconsin Supreme Court is expected to issue an order this week that lays the legal groundwork for a case that could decide the state’s political maps for the next decade.

While the order won’t be the final word in the case, it could settle key questions, such as whether justices should approve “least changes” maps that largely copy the redistricting plans Wisconsin Republicans passed in 2011.

States redraw their legislative and congressional boundaries at least once every decade following the release of U.S. Census data, a process designed to keep districts roughly equal in population.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Republicans controlled both the Legislature and the governor’s office during the last round of redistricting in 2011, which let them draw maps that helped them win big majorities over the past decade, even in years when Democratic candidates performed well statewide.

GOP lawmakers passed similar maps earlier this month, but Democratic Gov. Tony Evers vetoed the plans, saying they amounted to “gerrymandering 2.0.”

The conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, or WILL, filed a lawsuit in August arguing that given the likely impasse in state government, the fairest way for a court to resolve redistricting was by mostly preserving the 2011 maps, adjusting only where necessary to address population changes.

“The ‘least change’ approach is the most fair and neutral way for this Court to modify any existing maps,” WILL wrote in a brief filed last month. “It is the approach that best comports with this Court’s duty to assess the constitutionality of laws rather than to draft them from scratch.”

Democrats, and their allies, have urged a different approach, arguing that conservatives are asking the court “do their dirty work,” by entrenching GOP majorities in the Legislature for another decade.

“It’s bad enough that the legislature insulated itself from voters for the past ten years,” argued a coalition of Democratic voters including William Whitford, whose 2015 redistricting lawsuit made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. “It would be even worse if the Court were to perpetuate the gerrymander for the next decade.”

Federal courts have long had a hand in redistricting in Wisconsin, something Democrats hoped to continue when they filed a federal lawsuit on the day after the U.S. Census released its redistricting data.

State courts have had a more limited role in Wisconsin, where the state Supreme Court last handled redistricting in 1964. There are signs, however, that the current Wisconsin Supreme Court could play a larger role in redistricting.

In addition to agreeing to hear WILL’s lawsuit as an “original action,” justices issued an order in November promising to issue an opinion addressing three key questions in the case. They included what factors justices should consider in redistricting, whether a “least changes” map was desirable, and whether they should consider the partisan makeup of districts when evaluating or creating new maps.

The question of whether the court should consider partisanship is similarly divisive. Democrats and their allies want the court to consider the partisan makeup of districts, arguing that ignoring it could lead to another GOP gerrymander.

“It is essential that this Court not blind itself to the partisan effects of maps it considers and adopts,” read a brief from several groups including Black Leaders Organizing for Communities. “The unsubtle elephant in the courtroom is the fact that Wisconsin’s existing legislative maps comprise extreme partisan gerrymanders in favor of Republican politicians.”

Republicans, meanwhile, have urged the court to ignore partisan data, arguing there’s no fair way to measure it.

“There is nothing in the text of the Wisconsin Constitution that suggests that the framers intended to allow a claim of so-called partisan gerrymandering under Wisconsin law,” argued WILL.

Justices have also said their order will address whether they plan to consider the partisan makeup of legislative districts if they evaluate or draw new maps themselves.

Justices also ordered interested parties to file any proposed maps by Dec. 15 and set aside up to four days for a hearing or oral arguments on Jan. 15.

While the federal court hearing a challenge to Wisconsin’s could still play a role in the process, judges there have agreed to let the state lawsuit proceed first.

For more on the history of redistricting in Wisconsin and how it impacts political power in the state, check out WPR’s investigative podcast series, “Mapped Out.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.