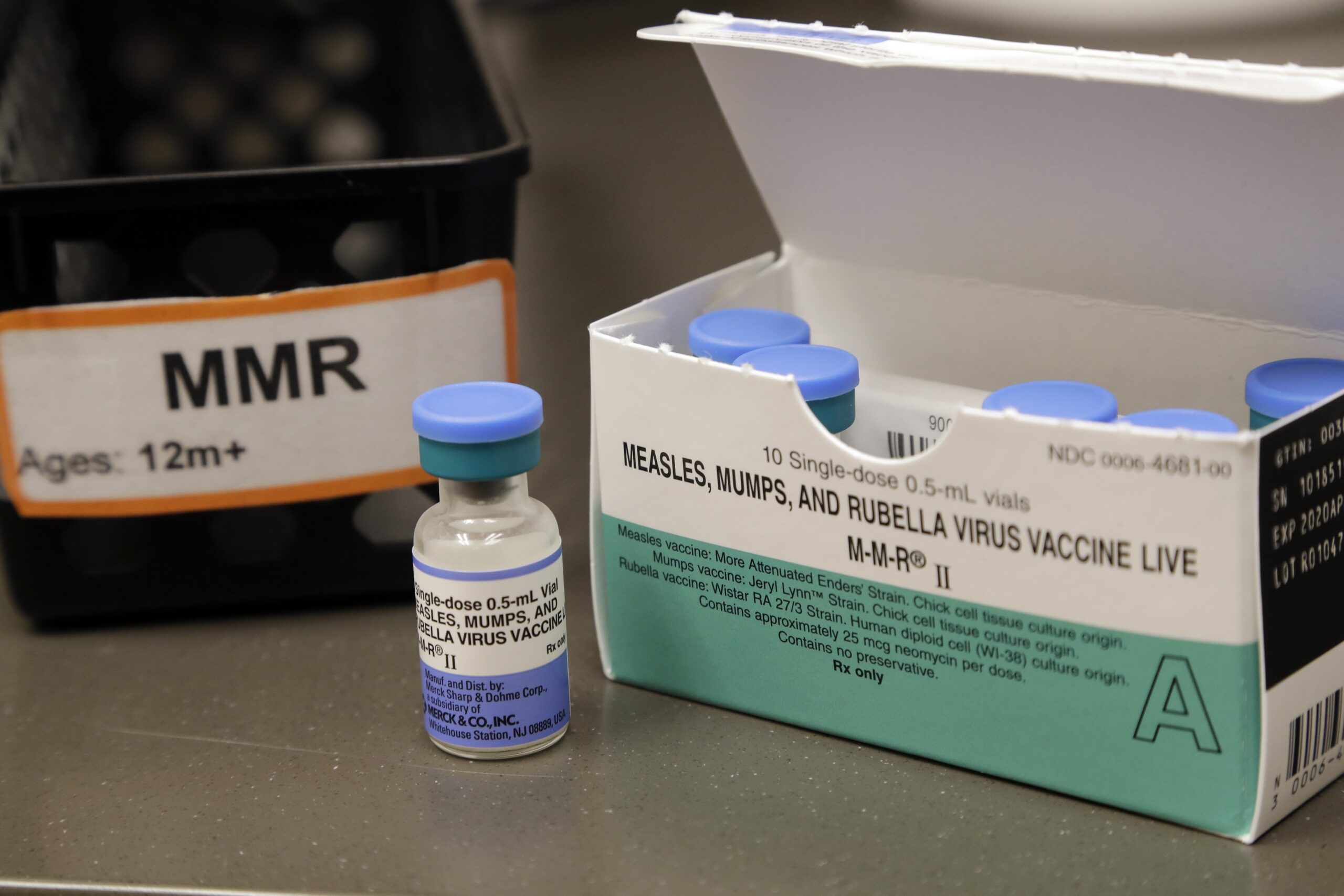

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison plan to meld computer modeling and social science in hopes of providing better responses to future pandemics. The goal is to be ready with quicker and more equitable strategies to distribute vaccines.

After the COVID-19 pandemic hit Wisconsin in February 2020, scientists, public health officials and lawmakers scrambled to catch up with the rapid spread of the virus. During the spring and summer, coronavirus testing kits were hard to come by due to supply chain issues and extreme demand. In the fall, Wisconsin hospitals quickly filled up with COVID-19 patients. And, once vaccines were given emergency authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, there were months of additional challenges getting enough doses to states and local communities.

In an effort to provide a better framework for distributing future vaccines, two UW-Madison researchers are working to create ready-to-use strategies for public health officials and policymakers.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

UW-Madison computer science professor Michael Ferris told WPR computer models he and colleagues developed over the past year have already been used by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. One model was developed to gauge options for potential hospital overflow sites. He said another was used earlier this year to help DHS plan vaccine distribution that included data from hospitals around the state.

“And it was really gratifying to have your mathematical models be impactful in a real setting,” said Ferris.

Ferris said he and his team incorporated data on geography, population health, age and social vulnerability metrics provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to distribute available vaccines.

“So, we over-allocated to places which were socially vulnerable and then the question comes out, ‘Well, is that an effective way of addressing those needs and or is there something that is missing?’” said Ferris.

UW-Madison Information School assistant professor Corey Jackson and his colleagues are searching for successful local campaigns aimed at making it easier for populations with less access to health care to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Jackson said some examples include Milwaukee County’s door-to-door vaccination program, which is working with volunteers to provide information and shots to residents of Black and Hispanic communities. Another, said Jackson, was an effort in Appleton, which created a pop-up vaccination clinic at a local barbershop.

Jackson said the goal is to find common mechanisms that are encouraging people to get vaccinated.

“And then hopefully, we’d be able to provide some sort of overarching description of these sort of localized vaccination encouragement strategies and how they’ve helped increase vaccination rates in the state of Wisconsin,” said Jackson.

Ultimately, Jackson said aspects of those strategies could be quantified and included in future computer modeling aimed at providing the most equitable and effective framework to determine how best to allocate resources, like vaccines, in the future.

Jackson said while their research is focusing on Wisconsin for now, lessons learned could be applied to other parts of the U.S.

Jackson and Ferris said much of their research revolves around equity and access to healthcare, but it could also be applied to finding more effective ways to address vaccine hesitancy.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.