Two rural Northwoods school districts will share a chemistry teacher, and they say the blended online learning program could be a model for districts across the state.

High school students in Phelps will learn chemistry from a teacher at Three Lakes High School.

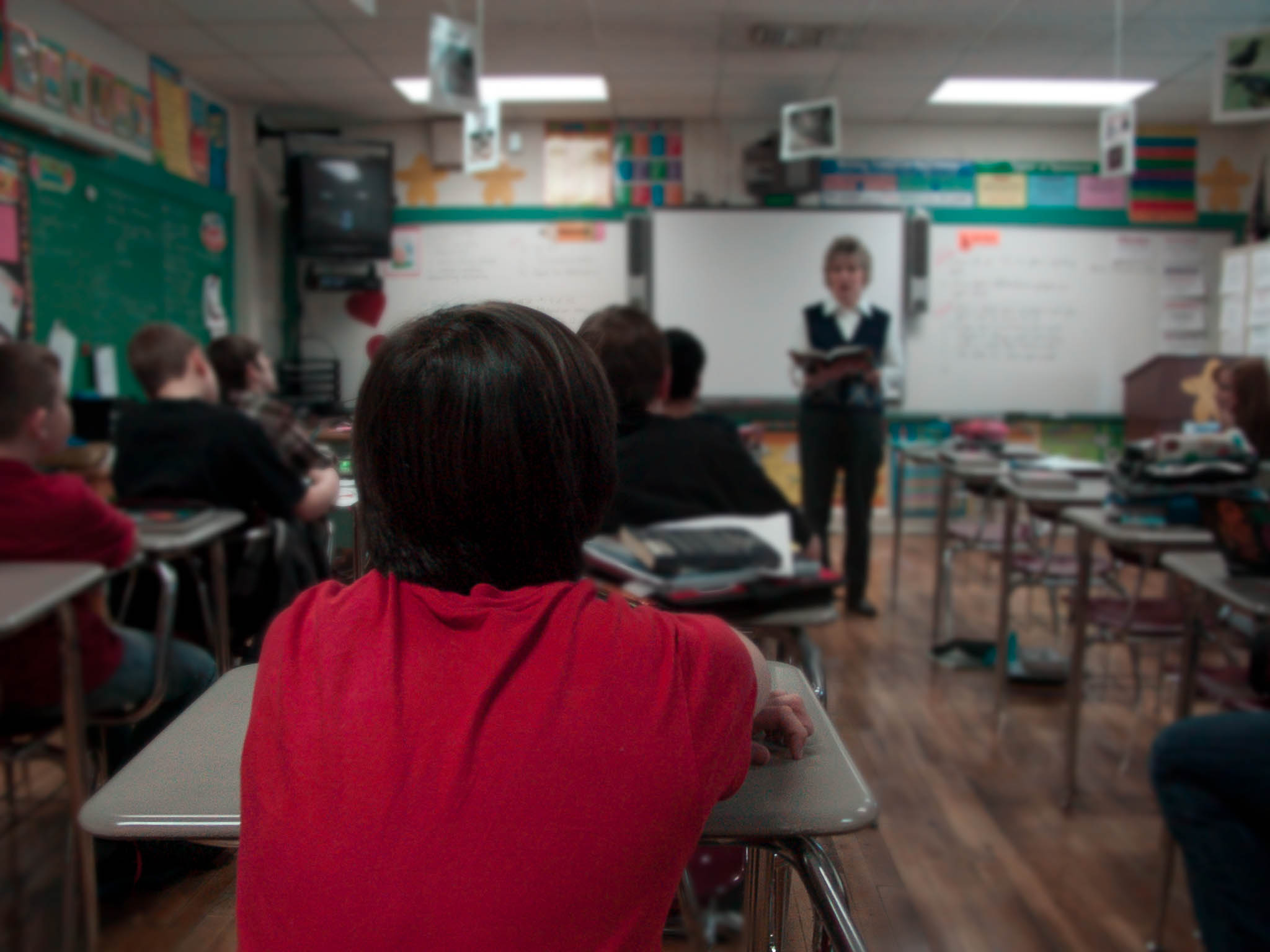

For the Phelps students, most of the instruction will happen through video lectures and online assignments. But there will also be a face-to-face component to the instruction, which could include travel by students or the teacher to the neighboring district.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

It’s an arrangement leaders in both districts say benefits their students and staff. And for rural districts facing declining enrollments and difficulty hiring new teachers, the cooperative program could be the start of a trend.

Phelps doesn’t have a teacher with certification to teach chemistry, said principal Jason Pertile, so students there have used online courses to take the class. In the past, that’s meant a fully asynchronous course, meaning students interact with a teacher only via email or other online messages. For those students, the new cooperative agreement means a closer relationship with their instructor, including the opportunity to ask questions during class.

“This is going to allow more hands-on activities, more interaction and more facilitating of conversations,” Pertile said.

It benefits Three Lakes, too, because it expands opportunities for teachers there, said Three Lakes High School principal Gene Welhoefer.

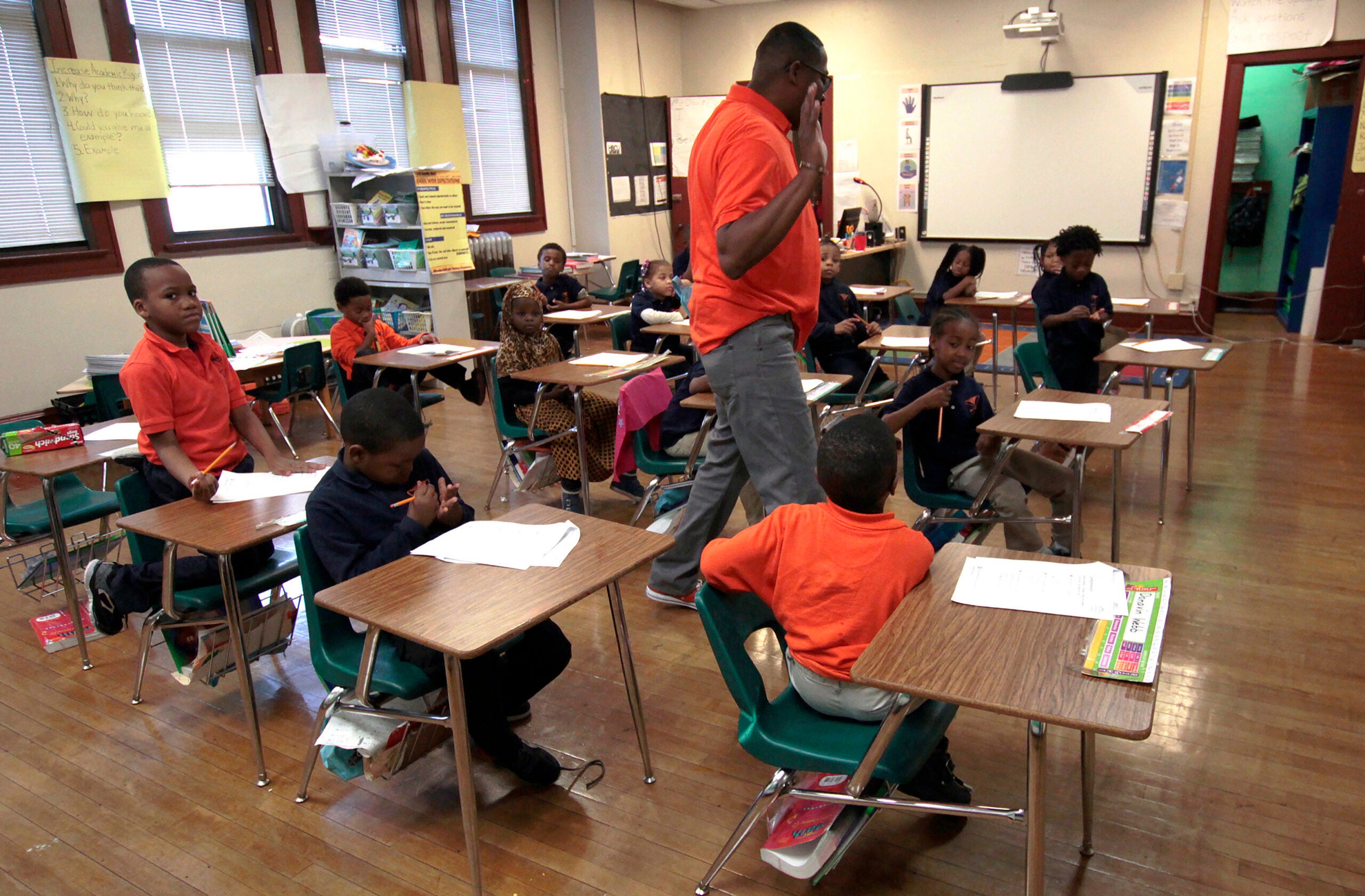

“Our teachers understand small, rural schools also, and know that we face enrollment challenges,” Welhoefer said. “And working with 20 students is much more meaningful than working with 10.”

The two districts, which are about a half hour’s drive apart through the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest in northern Wisconsin, already have a cooperative athletic program. A statement from the districts said the academic co-op was built out of that collaboration. Students had their first shared class Tuesday.

It’s the sort of arrangement that more and more rural districts will likely experiment with, said Kim Kaukl, executive director of the Wisconsin Rural Schools Alliance. That’s because it can help to address problems raised by both teacher shortages and declining enrollments in rural parts of the state while still maintaining some level of personal relationship between teacher and student.

“For a subject like chemistry, you may only have enough kids for one or two (classes),” Kaukl said, which may well mean a district can’t justify a full-time salary for a chemistry teacher. But listing for a part-time teacher only compounds hiring challenges. “If you can hire a quality person who can work full-time between the two districts,” Kaukl said, “that’s a positive thing.”

A shortage of teachers is a real challenge, said both Welhoefer and Pertile. They’ve both seen steady decreases in the number of applicants their schools get for open teaching positions.

“For smaller districts, the smaller you get, the more valuable those teachers become,” Pertile said. “With the teacher shortage, sometimes you just can’t find somebody who wants to come live in northeastern Wisconsin.”

Both districts are small and rural, but Three Lakes is the bigger partner. There are 38 students in the Phelps High School, and 127 in the whole district, Pertile said. Three Lakes had 148 students in its high school in the 2018-19 school year, and the district has more than 500 students. That’s one reason Phelps was already relying on virtual instruction for chemistry and some other elective courses. But Pertile said he’s already heard from a teacher at his school who is interested in exploring options for a blended-learning course that could be opened to Three Lakes students.

“I think it’s going to become a two-way street,” Pertile said. “We’re already talking about, ‘How can we expand this?’”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.